For the last decade, I’ve set a goal of reading (at least) 100 books per year. I have accomplished that goal nine out of ten years (missing the boat only 2017, when I clocked in at 97).

I started logging my reading in 2012 with a goal of 135 books a year, mostly because my friend Claudia Swisher was reading 135 books a year. I, however, am no Claudia Swisher—more’s the pity—and have had to convince myself that two books per week, with the elasticity of a nice, round-number goal is Good Enough.

Great, in fact. According to Pew Research Center, the average person reads 12 books per year. There’s even a little speed reading test to see how many books you could read if you read 30 minutes a day.

But I have my doubts about that statistic. Not that people aren’t reading—they are, probably more than ever. They’re increasingly sharing their thoughts about their on-line reading, as well. Books, not so much.

The whole ‘Do Your Own Research’ schtick is based on reading. The January 6th Insurrection was organized via social-media reading and writing. Spelling, no—but being a good speller is usually the result of doing lots and lots of reading (of correctly spelled and reasonably accurate text, of course).

I am a sucker for ‘best of’ lists, especially when I respect the (non-snooty) creator of said list. Here’s Barack Obama’s ‘best of 2021’ list (I’ve read three)—and a really great list of 2021 books from NPR staffers. But I also like lists—like mine, below—that loop older titles into the mix.

These are my five-star, recommended reads from the 110 novels and non-fiction titles I read in 2021. Eight fiction, six non-fiction. Fiction first, plus a disclaimer that I read voraciously and indiscriminately, and five-star my favorites, even if they’re not (ahem) literature.

Cloud Cuckoo Land (Anthony Doerr) It’s a difficult book to get into–and it’s long. You have to have faith that there will be an emotional payoff; it took maybe 100 pages before I started to feel like I was living in five stories simultaneously. There are moments in the book that are shattering–and poignant, and meticulously written (like the scenes during the Korean War, or the building of a cannon before the siege of Constantinople). And again, and again, the book makes us understand the terrible times we live in–that there’s essentially nothing new under the sun, just stories and human foibles.

Go Tell the Bees that I am Gone (Diana Gabaldon) I am a major Gabaldon fan—the only series that I regularly re-read—and it’s been more than seven years since her last ‘Outlander’ book. If you have only seen the TV show (which I also like, but feels pale next to Gabaldon’s writing and sense of time and history), you owe it to yourself to start with ‘Outlander’ (the weakest book in the series) and hang out with Jamie and Claire for a few decades, through the whole saga of nine. It’s a hard book to review (so much has Gone Before), but the book (all 888 pages) is loaded with small and lovely vignettes.

Early Morning Riser (Katherine Heiny) Jane, the protagonist is a second-grade teacher in Boyne City, Michigan (about an hour northeast of here) and all the local details ring absolutely true. The plot kind of meanders around, but every single one of the characters is uniquely drawn and…interesting. And the writing is spectacularly good, ranging from wise through long stretches of amusing with bolts of flat-out hilarious. Heiny gets school teaching (something authors frequently mischaracterize) absolutely right. She also gets love and marriage and life right.

Lightning Strike (Cork O’Connor) (William Kent Krueger) A Cork O’Connor ‘prequel’ where we learn some things about Cork’s boyhood, in a small northern Minnesota town, in 1963, where open racism was a daily occurrence.

Like all of Krueger’s books– his two standalones were also written from the POV of a boy–it’s easy to appreciate his flair for realistic dialogue. I spent 30 years teaching middle school boys, and Krueger gets their boy-boy smack-chatter just right. There’s one scene, in the last 25 pages of the book, of three boys sitting around a campfire, that feels like the dialogue from the movie ‘Stand By Me,’ which was adapted from a Stephen King story–half goofy, half profound. The book touches lots of subjects, especially growing up and understanding the world. It’s a well-written gem.

Hamnet (Maggie O’Farrell) Shakespeare is a very flawed husband, in this fictional account, and his creative, intuitive but illiterate wife is the one with strength of character, grounded in her village and close-to-nature way of life. The most wrenching parts of the book, however, are the life/death rhythms of living in the time of plague, the fragility of life. They make the book both beautiful and heart-breaking.

Firekeeper’s Daughter (Angeline Boulley) I live in Michigan, have been on Sugar Island, know the U.P. territory (rural poverty) and trust that Boulley has the language and setting and events right. Her desire, which took years to reach, was writing a book from the POV of an enrolled Tribal member, for teenagers. It seems right to me. Boulley shares the tensions between Native Americans and white people, and Daunis’s enrollment, in a way that feels authentic to me.

The Ministry for the Future (Kim Stanley Robinson) The book is about reversing changes to the biosphere and what happens if we don’t, so it’s a book about all of the lives of all of the people on the planet. It is wide-ranging, covering economic systems, political systems, technologies, crypto-currency and carbon sequestration, the internet and terrorism, just for starters. As soon as I started reading it, I looked at the world and the United States differently.

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue (V.E. Schwab) When you boil away all the historical references and characters (which I liked, a lot) and the romance, the story is one more Faustian fable–the devil cuts a deal and lets yet another clueless human live the life of what she believes are her dreams–with the moral being that nobody outsmarts the devil. Maybe. The story ends in a way I didn’t expect, but tilts the playing field and left me smiling, because Addie uses the oldest tricks (word chosen deliberately) in the book.

NON-FICTION: Two titles about racism (and a third that illustrates why white people have a great deal to answer for and understand); Two titles about sexism (and a third that loops in historic sexism around the topic of adoption).

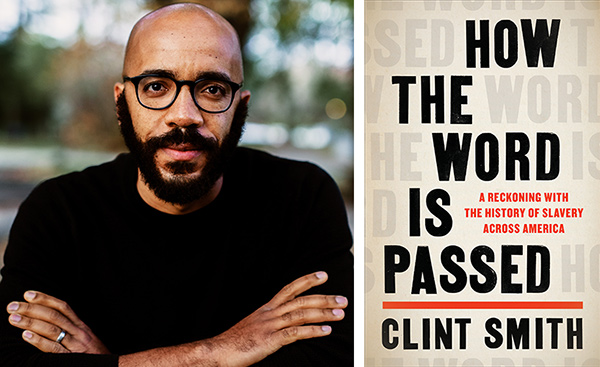

How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America (Clint Smith) This is the perfect book to read NOW. And by now, I mean in this stunning era, where states are passing laws to prohibit K-12 students from knowing about the bruising, wounding realities this book reveals. One short quote, from the chapter on Galveston Island and Juneteenth:

“Had I known when I was younger what these students were sharing, I would have been liberated from a social and emotional paralysis–a paralysis that arose from never knowing enough of my own history to identify the lies I was being old: lies about what slavery was and what it did to people; lies about what came after our supposed emancipation; lies about why our country looks the way it does today.”

American Baby: A Mother, a Child, and the Shadow History of Adoption (Gabrielle Glaser) There’s a lot of good information in the book–and things I’ve not put together, like the money-making aspect of the adoption industry and why their ‘evidence-based’ policies were created. But what makes the book memorable is Glaser’s case study, woven through the facts and figures. The end of the book, while sad, is also powerfully hopeful. As an adoptive parent, I’ve read lots of books about adoption. This is one of the very best.

Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women (Kate Manne) I would estimate that 75% of the facts, cases and statistics in the book were things I’d read before, but even if the book were a mere pastiche of Famous Misogynistic Stories, it would be useful, just to see all the evidence in one place. It’s more than that, however. I really appreciated Manne’s perspective on Elizabeth Warren: she was undeniably the most community-building, smart plan-crafting candidate for president, and why because of (not in spite of) that, she failed.

The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together (Heather McGhee) This may well be–like “Caste” in 2020–the best book of 2021, the book that helps white people understand how centuries of racist policy have hamstrung ALL of us (not just people of color) and made our world poorer and weaker. And it’s based on a nationwide array of examples of just how racist policy has not only left a legacy of inequity, but continues to shape our thinking and our prospects and opportunities.

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Robin Wall Kimmerer) Kimmerer is a lively writer, who weaves stories around data, and honors her Native ancestry and beliefs. I took lots of ideas away from the book, beginning with the fact that indigenous people lived in harmony with the earth for eons longer than the white people who make fun of their ‘primitive’ culture. It’s a book to make you re-think everything you believed about ritual and religion, fear of dying, the morality of climate change, even living through a pandemic.

Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male America (Ijeoma Oluo) A sober and research-based work, covering a disparate set of topics–politics, sports, education, media and women in the workplace. Oluo’s observations are intersectional in nature, demonstrating how things that seem ‘natural’–things ranging from salaries, power structures, health and welfare–appear that way because policies have been designed to keep them that way. By white men.