When I retired from teaching (after 32+ years), I enrolled in a doctoral program in Education Policy. (Spoiler: I didn’t finish, although I completed the coursework.) In the first year, I took a required, doctoral-level course in Educational Research.

In every class, we read one to three pieces of research, then discussed the work’s validity and utility, usually in small, mixed groups. It was a big class, with two professors and candidates from all the doctoral programs in education—ed leadership, teacher education, administration, quantitative measurement and ed policy. Once people got over being intimidated, there was a lot of lively disagreement.

There were two HS math teachers in the class; both were enrolled in the graduate program in Administration—wannabe principals or superintendents. They brought in a paper they wrote for an earlier, masters-level class summarizing some action research they’d done in their school, using their own students, comparing two methods of teaching a particular concept.

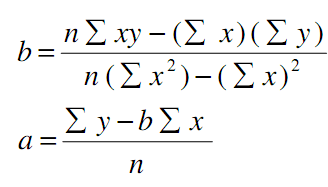

The design was simple. They planned a unit, using two very different sets of learning activities and strategies (A and B) to be taught over the same amount of time. Each of them taught the A method to one class and the B method to another—four classes in all, two taught the A way and two the B way. All four classes were the same course (Geometry I) and the same general grade level. They gave the students identical pre- and post-tests, and recorded a lot of observed data.

There was a great deal of “teacher talk” in the summary of their results (i.e., factors that couldn’t be controlled—an often-disrupted last hour class, or a particularly talkative group—but also important variables like the kinds of questions students asked and misconceptions revealed in homework). Both teachers admitted that the research results surprised them—one method got significantly better post-test results and would be utilized in re-organizing the class for next year. They encouraged other teachers to do similar experiments.

These were experienced teachers, presenting what they found useful in a low-key research design. And the comments from their fellow students were brutal. For starters, the teachers used the term ‘action research’ which set off the quantitative measurement folks, who called such work unsupportable, unreliable and worse.

There were questions about their sample pool, their “fidelity” in teaching methods, the fact that their numbers were small, and the results were not generalizable. Several people said that their findings were useless, and the work they did was not research. I was embarrassed for the teachers—many of the students in the course had never been teachers, and their criticisms were harsh and even arrogant.

At that point, I had read dozens of research reports, hundreds of pages filled with incomprehensible (to me) equations and complex theoretical frameworks. I had served as a research assistant doing data analysis on a multi-year grant designed to figure out which pre-packaged curriculum model yielded the best test results. I sat in endless policy seminars where researchers explicated wide-scale “gold standard” studies, wherein the only thing people found convincing were standardized test scores. Bringing up Daniel Koretz or Alfie Kohn or any of the other credible voices who found standardized testing data at least questionable would draw a sneer.

In our small groups, the prevailing opinion was that action research wasn’t really research, and the two teachers’ work was biased garbage. It was the first time I ever argued in my small group that a research study had validity and utility, at least to the researchers, and ought to be given consideration.

In the end, it came down to the fact that small, highly targeted research studies seldom got grants. And grants were the lifeblood of research (and notoriety of the good kind for universities and organizations that depend on grant funding). And we were there to learn how to do the kind of research that generated grants and recognition.

I’ve never been a fan of Rick Hess’s RHSU Edu-Scholar Public Influence Rankings, speaking of long, convoluted equations. It’s because of these mashed-up “influence” rankings that people who aren’t educators get spotlights (and money).

So I was surprised to see Hess proclaim that scholars aren’t studying the right research questions:

There are heated debates around gender, race, and politicized curricula. These tend to turn on a crucial empirical claim: Right-wingers insist that classrooms are rife with progressive politicking and left-wingers that such claims are nonsense. Who’s correct? We don’t know, and there’s no research to help sort fact from fiction. Again, I get the challenges. Obtaining access to schools for this kind of research is really difficult, and actually conducting it is even more daunting. Absent such information, though, the debate roars dumbly on, with all parties sure they’re right.

I could tell similar tales about reading instruction, school discipline, chronic absenteeism, and much more. In each case, policymakers or district leaders have repeatedly told me that researchers just aren’t providing them with much that’s helpful. Many in the research community are prone to lament that policymakers and practitioners don’t heed their expertise. But I’ve found that those in and around K–12 schools are hungry for practical insight into what’s actually happening and what to do about it. In other words, there’s a hearty appetite for wisdom, descriptive data, and applied knowledge.

The problem? That’s not the path to success in education research today. The academy tends to reward esoteric econometrics and critical-theory jeremiads.

Bingo. Esoteric econometrics get grants.

Simple theoretical questions—like “which method produces greater student understanding of decomposing geometric shapes?”—have limited utility. They’re not sexy, and don’t get funding. Maybe what we need to do is stop ranking the most influential researchers in the country, and teach educators how to run small, valid and reliable studies to address important questions in their own practice, and to think more about the theoretical frameworks underlying their work in the classroom.

As Jose Vilson recently wrote:

Teachers ought to name what theories mobilize their work into practice, because more of the world needs to hear what goes into teaching. Treating teachers as automatons easily replaced by artificial intelligence belies the heart of the work. The best teachers I know may not have the words right now to explain why they do what they do, but they most certainly have more clarity about their actions and how they move about the classroom.

In case you were wondering why I became a PhD dropout, it had to do with my dissertation proposal. I had theories and questions around teachers who wanted to lead but didn’t want to leave the classroom. I was in possession of a large survey database from over 2000 self-identified teacher leaders (and permission to use the data).

None of the professors in Ed Policy thought this dissertation was a useful idea, however. The data was qualitative, and as one well-respected professor said– “Ya gotta have numbers!” There were no esoteric econometrics involved—only what teachers said about their efforts to lead–say, doing some action research to inform their own instruction–being shut down.

And so it goes.