I just finished Rachel Bitecofer’s feisty, punchy book on political messaging, “Hit ‘Em Where it Hurts: How to Save Democracy by Beating Republicans at Their Own Game.”

Recommended—although not, as the subtitle suggests, to beat Republicans at their own despicable, even shocking, game. Recommended because we’re in crisis, and being smarter and nicer is no longer cutting it.

In December of 2020, I wrote a blog entitled Republicans. Up until that point, in my political perspective, there were country-club Republicans who were conservative, in the traditional sense of keeping things that preserved beneficial aspects of their lives in place. And there were the rabid right-wing crazies who emerged like locusts after Barack Obama was elected. But the two were merging, and the outlook for keeping two distinct parties that counterbalanced each other’s policy goals, for the good of the nation, was dim. The Republicans were ruining democracy. On purpose.

I took some grief for that blog, from die-hard moderate Republicans (who are thick on the ground where I live and work), and also from some Democrat friends who thought it took me way too long to outright reject and stomp on anyone who voted Republican in the past two decades.

From the standpoint of March 2024, and Rachel Bitecofer’s crisp and direct prescriptions for saving democracy, however, my hardcore Dems friends were right: You don’t get anywhere with a mushy message, a bunch of facts, and reaching across the aisle. And you can’t share those great policy ideas unless you can get elected.

I blame my 32-year career as a public-school teacher for this habit of equivocating and looking for points of agreement. I spent most of my time trying to reduce conflict, banish name-calling, find common ground, and build functioning communities in my middle school classroom.

So many communities. I was partially successful at this, more so toward the end of my career. If kids don’t get along, after all, they can’t make music together. This is the single most important reason I stopped having chairs and challenges, and tried to avoid unnecessary competition. Teachers everywhere want their students to be able to work together despite differences. It’s what we do.

Bitecofer’s take on political messaging is that Republicans have zero interest in working together to solve problems. They just want to retain power. It’s time for Democrats to boldly claim the high moral ground, she says, rather than using data and reason to present their detailed policy plans, no matter how forward-thinking and appealing they may be to Democrats.

We’re getting beat up, she says, by sophistry. Time to call a lie a lie. To fight back. To take back the word freedom, for starters. We are clearly the party that supports freedom, around the globe, and here at home. Why aren’t we claiming that? The losses that we are suffering now—reproductive freedom, the freedom to vote, the freedom to breathe clean air—have not come from Democratic actions.

She points out that education has generally been seen as a Democratic issue, back to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in the 1960s (along with minority rights, infrastructure and health care), but the 2021 Gubernatorial election in Virginia turned that around—with a big fat passel of lies about what was happening in public schools.

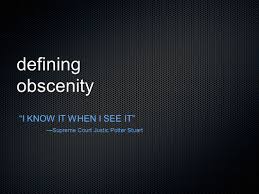

You remember— charges that teachers were making white kids feel guilty via CRT, encouraging transgenderism and putting out kitty litter for the furries. The kinds of things Dems responded to by politely explaining that critical race theory was an advanced concept, first introduced by Kimberle’ Crenshaw, interrogating the socially constructed role of race and institutionalized racism in society, yada yada.

All true. But completely overridden by the Republicans’ simple, dishonest message: Schools are taking away parents’ rights! (Even though parents have always had rights.) Bitecofer, lurking in the background, would say: Don’t bring reality and truth to a Republican messaging war, because Republicans trust feelings, not facts.

Democrats have, for decades, rallied around more resources and equity for public education. They have gone to schools and registered newly minted 18-year-old voters. They have defended the wall between church and state, pushed back hard against vouchers for the wealthy. Time to claim credit.

America is a uniquely apolitical country, Bitecofer says, with little civic culture. This benefits Republicans, who count on people to vote out of old partisan habits, not new information.

Occasionally, someone will claim that more or better Civics classes would improve engagement in electoral politics in the United States. I seriously doubt that, especially since the things that make the study of Civics engaging and sticky are precisely the things that Ron DeSantis is passing laws against. Kids learn to be good citizens by watching adults—a statement worth pondering, in this election year.

Pick up Bitecofer’s book—it’s a short, easy to digest read. Then pull on your metaphorical boxing gloves.