From a great column, by Darrell Ehrlick, on paying attention to the news, in the Michigan Advance:

I understand the dark headspace a person can occupy after consuming a steady diet of news that seems to indicate a growing danger of authoritarianism; of a broken political system that continues to perpetuate dysfunction instead of listening to a public hungry for cooperation and solutions; of one global crisis after another; and of a global climate catastrophe so profound it threatens the very existence of the human species.

Yeah. That dark headspace.

For several years, since retiring, we have temporarily escaped harsh Michigan winters, spending the month of February in Airbnbs in Arizona. None of them had cable TV packages, so news-watching was limited to MSM, and sometimes, not even that. And eventually, we began to notice how agreeable it was to avoid what was happening in the Trump administration, dodge endless outrage over the January 6th insurrection, and reduce the non-stop anxiety of COVID spikes and variants.

No news, apparently, is good news.

Ehrlick’s point was—as you may have guessed—that it’s now incumbent upon all comfortable Americans to pull their heads out of their sulky discontent over restaurant wait times and gas prices and re-engage with civic responsibility. A republic, if you can keep it, and all that. The title of the piece is: Democracy is on fire. Consider this your wake-up call.

We’re seeing this wake up! language everywhere, lately, and not just in rabid, perennially anti-Trump commentary. As we round the corner into 2024, and the Election Where Nobody Wins gets closer, our obligation to choose wisely looms. Ehrlick is right—when the former leader of the free world is calling his enemies “vermin,” and pre-planning his political revenge tour, and the Speaker of the House can’t distinguish between facts and lies, we’re in a bad headspace, indeed.

What was once considered hype, rhetorical overkill, playing the fascism card, etc. etc. is beginning to feel important and very credible. To political writers and news analysts, like Darrell Ehrlick—but also to invested citizens, like me. The old saw about being condemned to repeat a past one can’t remember is newly fresh and relevant—and omnipresent in the media.

And—surprise!—our older students are impacted by the same real and important political instability, as well. I think a whole lot of the ugly blah-blah promulgated by Moms for Liberty types is generated by parents’ wishes to keep their children from experiencing that dark and questioning headspace. There are plenty of “cultural chaos agents” ready and willing to help helicopter moms with that goal, then cash in after the election. It also helps to explain why the most zealous M4L acolytes are those with the most to lose by pursuit of diversity and equity. Keeping calm and carrying on while trying to solve problems that impact us all is not a way to preserve privilege.

All they have to do is convince anxious parents that the K-12 sky is falling. That their kids can’t read competitively by age eight, because their instructors are incompetent. That environmental science is promoting clean energy, undercutting the fossil fuel industry. That elementary school teachers are urging first graders to reconsider their gender, when the curriculum actually prescribes a foundation of respect and understanding for other people. That it might be a good idea to totally defund public education, and throw in public libraries and museums as well.

So many manufactured crises. So much to lose.

And although teachers are my favorite people on the planet, I have to admit that a lot of us are also inclined to—cliché alert—close our doors and teach, as policy and negative media opinion swirl around us. I get it. I am intimately familiar with the most pressing concern for teachers, especially novice teachers: What am I going to do tomorrow? And how will it prepare my students for their diverse futures while keeping their standardized test scores up?

Mostly, this is a matter of limited human time and energy. We are firefighters, dealing first with the urgent, and later with the important and long-term issues. Studying worst-case news and opinion—the dark headspace in education—can lead to a kind of paralysis for educators.

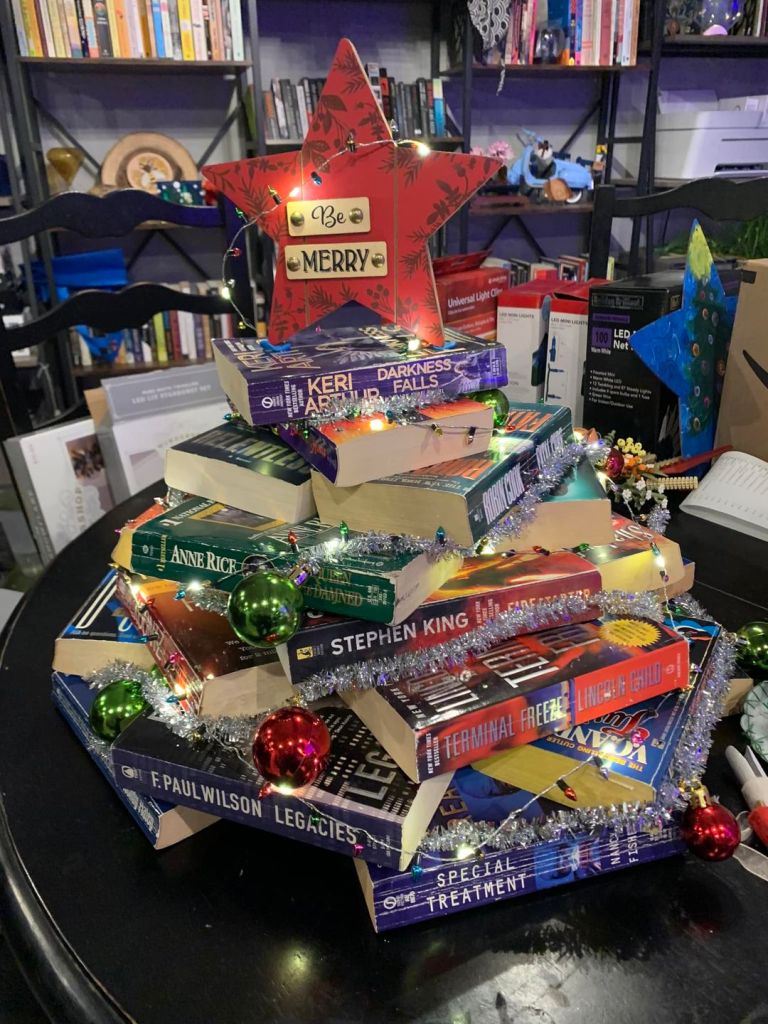

Things like choosing the perfect books to expand students’ minds and imaginations– see Mandy Manning’s photo illustration, a mélange of horror books, light and love–become minefields. If we’re not letting our students safely wrestle with the idea of a dark headspace through literature, history, drama and current events, how will they learn to cope?

Shortly after No Child Left Behind (the law to permanently fix all our public schools) was passed, I took a sabbatical—a perk in our local contract—to work for a national non-profit. While there, I spent a lot of time dissecting the new law, and its impact on highly qualified teachers, both the ones who were labeled highly qualified under the law, and the teachers who actually were exemplary, according to their school leaders, parents and students. I went to D.C. and spoke with folks in the Education Department, who were trying to figure out the laws’ outcomes, as well.

When I returned to the school where I taught, I was in a union meeting where the local Communications VP was cluing members in on the new legislation, which he called the ‘Adequate Progress’ law. But don’t worry, he said. Our contract prevents administrators from transferring us because we don’t have the right credentials. I raised my hand and gave my colleagues a quick summary of NCLB—the HQ teacher part, the adequate yearly progress part, the testing part, and more.

Our good contract won’t protect us from requirements of federal law, I explained. There was silence in the room. The idea of federal law mandating testing as early as 3rd grade, of tests determining a teacher’s value, of a district losing control over who is best positioned to teach a grade or subject, of national curricular standards—those were new and terrifying ideas.

Ideas, I might add, that teachers have pretty much absorbed in the intervening 20-odd years. Which ought to be a cautionary tale.

Living in a dark headspace is a call to action.