Here’s a truism that educators repeat endlessly (and, apparently, fruitlessly): Just because you went to school, doesn’t mean that you understand how schools work.

It applies to all the logistical and philosophical details about schooling, from busing to teacher prep to grading. Just because you had three recesses per day in elementary school doesn’t mean that kids in 2023 have that essential play built into their days. Just because you took Algebra I in ninth grade doesn’t mean that your seventh grader won’t have single-variable equations in their homework packet. Just because teaching seemed easy (or dreadful) to you, as a child or teenager, doesn’t mean that anybody can do it.

And so on. You don’t know what’s going on in schools—or why—unless you’re there all the time and have deep knowledge of education policy and practice.

In a wonderful piece in his eponymously named blog, Tom Ultican writes about a deal going down in Texas:

Under this new legislation, the state of Texas is contracting with Amplify to write the curriculum according to TEA guidelines. Amplify will also provide daily lesson plans for all teachers. The idea is to educate all Texas children using digital devices and scripted lesson plans while teachers are tasked with monitoring student progress.

This, of course, is not new at all. Education publishers and nonprofits have been hawking standards / curricula / benchmarks / instructional materials / “innovative” reforms—all of them ‘aligned’—for decades, ramping up this effort post-NCLB, and culminating in the Great National Project to Standardize Everything, the Common Core.

Tom does a superb job of deconstructing the fallacy of one-size-fits-all lesson plans, as well as giving his readers a heads-up about Who Not to Trust in Ed World and what they really want.

I was struck by this quote from the so-called Coalition for Education Excellence (“Reducing teacher workloads with State support”):

“Many teachers in Texas are currently working two jobs—designing lessons and teaching them—which is contributing to their exhaustion and teacher shortages. Access to high-quality instructional material can reduce teacher workloads and play a critical role in delivering quality education.”

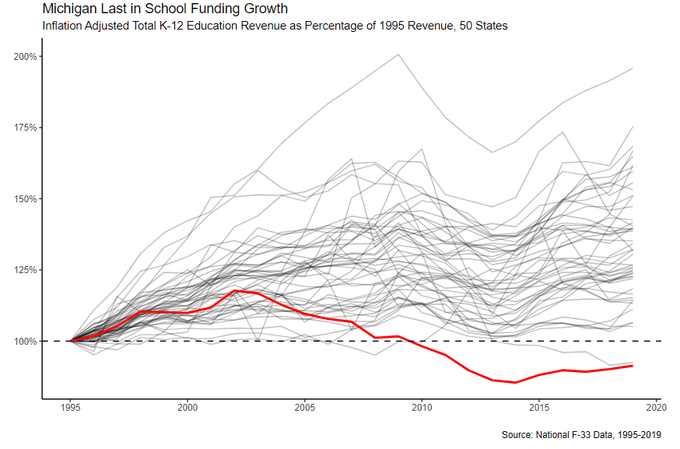

I have no doubt that many Texas teacher are actually working two jobs, given that the minimum salary for 5th-year TX teachers (who have certainly created lots of lesson plans at the point) is less than $40K. I imagine asking that 5th year teacher if he would rather have more money or free (mandated) lesson plans, courtesy of Texas, which has already spent more than $50 million on the pre-designed, screen-ready lessons from Amplify.

Here’s where the lack of insider knowledge—”just because you went to school…”—comes in, at the intersection of curriculum and instruction. I guess that free (mandated) lesson plans might sound like a good idea to someone whose conception of instruction was formed by the conveyor belt of students with flip-top heads featured in “Waiting for Superman,” another artifact of the roiling education reform dialogue.

No amount of marketing pomposity can change the fact that teachers, in order to be effective, need some control over their professional work. Effective teaching goes like this:

- Get to know the students you’re responsible for—their strengths, their shortcomings, their quirks. Let them know you care about them, and intend to teach them something worthwhile.

- Using that knowledge, design and teach lessons to move them forward. Persist, when your first attempts fail or produce mediocre results. Check on their learning frequently, but let them know that you’re checking in order to choose the right thing to do next—not to punish, or label them. Re-design lessons using another learning mode, accelerate, cycle back to review, pull out stragglers for another crack at core content, challenge those who have mastered the content and skill with enrichment activities—and do all of this simultaneously, every hour of the school day.

In other words, designing lessons and teaching them cannot be separated, if you’re hoping to create a coherent curriculum or motivated learners. They’re entirely dependent on the students in front of you. Removing one of the two from the equation makes it harder, and more time-consuming, if the goal is crafting a learning classroom.

One of the phony reasons for adopting the Amplify curriculum TX state legislators have been fed is that students were being taught “below grade-level content.”

It would be easy for those without experience as educators to assume that kids in Texas were being short-changed, left behind, by feckless teachers lazily spoon-feeding them easy subject matter.

There might be actual reasons for this: some curricula is best understood and applied when taught sequentially. A sharp teacher, getting to know her students, can identify gaps and address those before moving to the next stage—a far better and more efficacious plan than starting with whatever the state has designated as “grade-level.”

The grade-level curricula may be inappropriate for some kids (special education students spring to mind here). It may have been set by people who haven’t been in a classroom in decades, or don’t understand what the pandemic—or poverty—have done to students in any given state or town.

Lesson planning and its partner, effective instruction, are things that teachers get better at, year after year. They are a central part of what it means to be a good teacher. Taking lesson planning away from an entire statewide public school system is not an act designed to make teachers’ lives easier.

It’s about control over what gets taught.