This is a blog about the escalation of smack talk—the reckless/threatening/false/vindictive/facetious things people say, in an effort to gain power by demeaning others– and a thought or two about how much easier it is to be a smack-talker in 2022 than just a few years earlier.

We’re also seeing more smack talk in schools and about schools. Critical race theory and learning loss are among the many widely abused terms that media perceives as real issues. The terms are essentially meaningless, however, in the daily operation of real schools, places where teachers are paying attention to the well-being and nascent citizenship of real children.

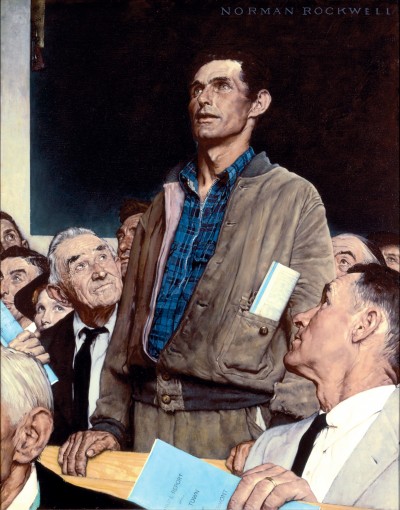

These days, schoolboard meetings are hotbeds of vigilantism driven by smack talk, and we’re witnessing members of Congress—Congress! —trash the sitting President’s strength and motives during a delicate and critical time of international unrest.

Traditionally, school is a place where smack talk is not tolerated, even if it is a regular feature of students’ home life. Poor-mouthing classmates, the use of offensive language, and overt lying are generally suppressed by school cultures, even strongly authoritarian climates where teachers use harsh language to control students.

Every now and then, someone points out that what our students need most now is not Calculus, but media literacy, a carefully developed skill of discretion when bombarded by corrupt but persuasive language. We used to worry about students being overly influenced by Bart Simpson or semi-dressed babes on MTV—but these days, the filthiest and most damaging lies are coming out of the mouths of politicians and news media. How do you teach kids to ignore their own duly elected Senator?

In 2017, I was part of a local ‘listening tour’ sponsored by my county Democratic party. We knocked on doors and asked people what they wanted from their local government. We wanted to know what their issues and needs were, for upcoming campaigns—but were also willing to listen to their feedback on the 2016 election. We did not call on strong or ‘leaning’ Republicans—only independent voters and those who may have leaned our way at one time.

What we learned: every single person we talked with had a distinct opinion on Trump vs. Hillary (the gender dynamics of the last name/first name contrast being kind of smack-y in itself). Most were willing to tell us who they voted for, and why, although we were trained not to ask.

They did not like or trust Hillary Clinton—and the ones who declared themselves Trump voters were clear about what attracted them to him: the way he talks. He says what he thinks! He isn’t mealy-mouthed like other politicians. He’s down to earth, but strong. His disrespect of women was ‘just locker room talk.’ More than once we heard: Give the guy a chance. Asked about local issues and government, most of them had no ready response.

What our neighbors had to say was almost completely unsubstantiated and unrelated to governing or current issues, not to mention decades’ worth of real facts about Trump’s history as grifter and narcissistic braggart. They took the measure of a candidate by his (or her) willingness to make insulting remarks. To get in a good dig, to trash your opponent. A few men spoke admiringly about Trump literally stalking or silencing Clinton on the stage, during their debates. He was a ‘fighter’—and would fight for us. Which ‘us’ they were talking about was unspoken.

Although hard to prove, beyond prima facie observations, smack talk has become more prevalent everywhere in American life. In my former State House district, for example, one of the Republican candidates told the crowd at a rally to “be prepared to lock and load,” and “show up armed” when going to vote. A Republican gubernatorial candidate suggested voters pull the plug on voting machines, if they didn’t like what they saw at the polls.

Are K-12 students influenced by this kind of loose, vindictive talk? Recently, at a school basketball game, students from a 95% white rural school made monkey noises and used racist insults when Black players on the opposing team were on the court. The report talks of similar occurrences at other games, listing several of these over the past two years.

What interesting to me is the response from the MI Department of Civil Rights: “To ignore the situation without taking those individuals who perpetuated it to account causes a problem and obviously allows it to occur again. So that situation should be controlled not only by the people who are officiating the game, but also the officials who certainly have some control over the students and the actions that they might have later on or during the game itself.”

I agree. Racial slurs and dangerous threats are best handled when they first emerge by the people closest to our students. This is what lies under at anger over faux CRT—adults influencing children to analyze their own prejudice, and respect differences. Good teachers have always done this; it’s the practice of building a classroom community.

So it’s no wonder that judgmental terms like ‘learning loss’ have caught on, and Serious Reports are warning that children in poverty have ‘lost’ the most. All children have been exposed to danger and loss during this pandemic, but whether they’re testing on grade level—whatever that is—should be the least of our worries.

We should be thinking, instead, about turning them into caring and confident citizens, able to identify coarse and deceptive language and reject it.