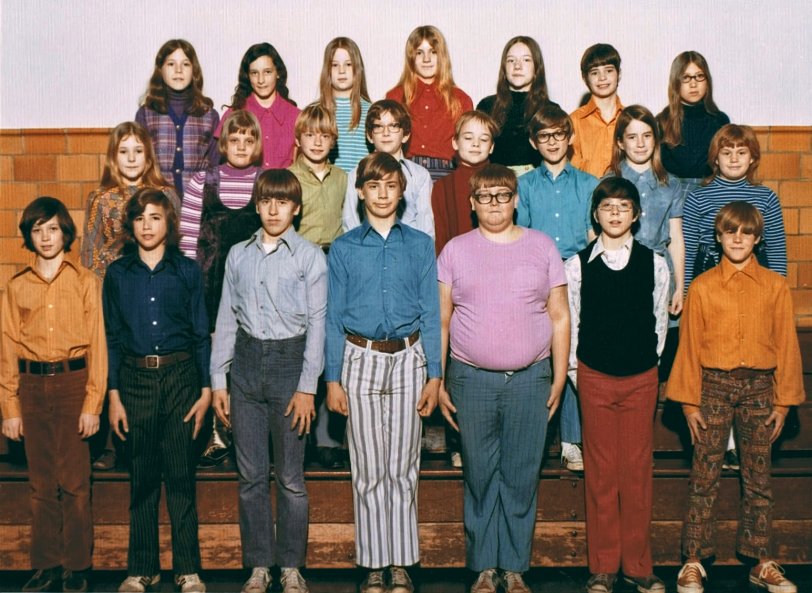

The first time I was called on the carpet by a parent for something I taught was in my first year of teaching. In the 1970s. The fact that I remember it so clearly, decades later, is significant.

Here’s what happened: I was teaching my sixth grade general music classes about song parodies. We didn’t fret much, in those days, about standards, benchmarks or learning goals, but I actually had some.

I wanted my students to understand how one tune could carry multiple sets of lyrics—that they were two separate things, and the character and tempo of the tune should match the words, ideally. The tunes, written on the board (this was in the days of pre-lined music chalkboards), would illustrate new rhythmic figures. And writing their own words would be an exercise in creativity for the students.

This was before Weird Al, but I encouraged them to use popular songs, and adapt the words. They worked in little teams, then shared what they’d come up with. A group of boys used the Beatles’ Maxwell’s Silver Hammer, substituting Santa for Maxwell (it was December). Of course, the class thought this was hilarious: Bang, bang, Santa’s silver hammer came down on her head… (and made sure she was dead).

I can’t remember, exactly, how I responded to the boys’ warbling this song. But the next afternoon, I was called to the principal’s office. A mother had called, all upset about what I was teaching my sixth graders—something about Santa being a killer? Surely, that couldn’t be right. Could it?

I explained.

Do you want me to handle this? he asked. (Props to him.) He thought it would be better for me to talk to the mom but was willing to run interference. I’d been a music teacher for all of four months, and it was tempting to avoid that conversation, but I told him I’d call her back tomorrow.

Which was good. It gave me an evening to run through the gamut of emotions. Defensiveness. (I didn’t know what the boys were going to sing!) Scorn. (Shouldn’t a sixth grader be a little tougher? Even with a helicopter mom?) Fear. (What if the mom took this higher than the principal—could I be formally reprimanded? Did she have friends on the school board?)

The next day I called her back and essentially fell on my sword. I explained what I was trying to teach, and how the lesson got away from me. I skipped the defensiveness, scorn and fear. She explained that her daughter still believed in Santa Claus and came home devastated and sobbing when those awful boys thought it was funny for Santa—the real Santa—to be so unfairly portrayed. She talked about Santa as the embodiment of fun and joy and childhood.

I did some private eye-rolling, but I apologized, and promised to have a chat with the class the next time I saw them and enlighten them about inappropriate lyrics. She said she felt much better after speaking to me. And—here’s the important part—I had three more children from that family in the music program over the years, with good relationships all around.

When I told the principal about our conversation, he pointed out that sixth grade, the first year of middle school, is scary for sheltering parents. They fear their children’s maturation, often wanting one more year of childhood, to stop the adolescence train from its inevitable arrival. He complimented me on handling it professionally. (He really was a great principal.)

Since that day, I’ve had hundreds of difficult conversations with parents. But very few of them were about what I was teaching—the learning goals, teaching materials, class discussions and curriculum. For more than a dozen years, I took more than 100 8th graders on overnight trips—to see musicals and orchestras, to play a concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, to visit the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. There were risks in that—but also great rewards.

I also wove what you might call controversial topics into my lessons. The ethical dilemmas of downloading ‘free’ music in the days of Napster, for example (when I knew full well that there was illicit downloading going on in many of their homes). The Black roots of American popular music, and our shameful treatment of some of our most influential artists, including theft of their genius. I did a mock trial around sexism in rock music.

My school was 98% white and very middle class, with lots of stay-at-home moms, in a ruby red county. I was able to do this because I built up trust in the community over time. I told parents, at Back to School night in September, what I was planning and why—the broad outlines, anyway.

I say all this not to congratulate myself on being a model, DEI-friendly teacher. I’m telling you that most of what is happening at school board meetings right now, and all of the proposed legislation to insert parent surveillance into instruction, comes from a very different source than helicopter parenting. It’s a gross political calculation, with ugly threats and outright falsehoods upping the ante.

It springs from defensiveness and scorn—I’m entitled to have control over my children’s beliefs, not some left-wing, bottom of the barrel teacher’s BS! But mostly, it’s about fear. That fear was nurtured in concert with four years of terror over and lies about losing political power–plus racial, sexual and xenophobic animus.

And now we have stupid laws, like the GOP bill popping up in near-identical form in states with Republican-dominated legislatures.The language demands ‘transparency’ around several things:

- Curriculum approved by the district for each school operated by the district.

- Each class offered to pupils of the district as part of the curriculum.

- A list of each certificated teacher or other individual authorized under state law to teach in this state who is charged with implementing the curriculum.

I cannot imagine any public school district in the United States that couldn’t provide that information in about 20 minutes, unless they were operating in utter chaos, in which case they have bigger problems than answering parents’ (legitimate) questions about what their kids are learning.

Here’s where it gets a little dicey—and insulting. The law also mandates the sharing of:

- Textbooks, literature, research projects, writing assignments and field trips that are part of the curriculum.

- Extracurricular activities being implemented during designated school hours or under the authority of the school.

And there’s a walloping big threat tucked in:

- School districts that don’t comply would lose 5 percent of state funding.

Teachers all over the country have been exclaiming how just how nuts this ultimatum is. Good teachers identify student needs and base their lesson plans on what logically comes next, for the kids in front of them. And often, a great lesson opportunity, something not in the formal curriculum, emerges unexpectedly. Teachers know this as the teachable moment.

Here’s an example of that: I was teaching a 7th grade math class and we had just finished a unit on ratios and percentages. We did pages of calculation, and had a culminating test, but I wasn’t convinced the students knew the utility of ratios and percentages in adult life. I was reading the Sunday Detroit Free Press and there was a four-page feature article on changing housing prices and mortgage rates, with lots of tables and graphs. Eureka.

This was before the days when students had their own devices, so I copied and pasted parts of the article into a packet, and we dug into the costs and financing of homes. The first thing that happened was the shock of a bunch of 12 year-olds learning that their homes probably cost more than $100K, which seemed like a fortune to them. We calculated down payments for the homes they chose from pictures in the article, and monthly payments using different mortgage rates. It was actually fun.

It was basic math, the kind of thing parents always say that they want: practical finance. Would they still say that, today? Would there be a parent who found a lesson like this intrusive, giving students information about the comparative value of homes in disparate neighborhoods—or predatory lending? And would they be able to shut this lesson down, for all the students?

Needing to pre-approve every single thing—not just books–that teachers use in instruction would be extraordinarily clumsy. It would suppress creativity, but innovative lessons around current conditions and events now feel dangerous to some parents (check the link for just who those parents are).

The ‘extracurricular’ reference likely refers to clubs and activities where there is less oversight— like the drama club, school newspaper, or the Gay-Straight Alliance, things that make school rewarding, even bearable, for many students.

Here’s the key thing, though. It is exceptionally difficult to predict or control what gets said and done in schools, even with an ironclad curriculum, because the school staff aren’t the only ones talking. The kids are talking, too. My lesson on song parodies didn’t go awry because of anything I did or said. And ask any kindergarten teacher how much they hear about what goes on in their students’ homes.

There’s lots of transparency in schools—they’re among the most transparent and accountable public institutions on the planet. And that’s a good thing.