I don’t know a single teacher—not one—who has never left school on a Friday afternoon wondering if, just maybe, they should have gone into real estate instead. Under the best of circumstances, teaching is ridiculously hard work, dependent on never-guaranteed intrinsic rewards, rather than perks, benefits and salary, to maintain employee motivation.

The autonomy and supports necessary for a well-resourced, custom-tailored occupational package for professional educators have been in short and diminishing supply for a couple of decades now. Worse, the profession drains our energies, taxes our personal and communal resources, and has become increasingly driven by top-down data collection. Teaching, as Lee Shulman famously said, is impossible.

And then we had a pandemic.

The papers are full of stories about people quitting or not returning to their crappy (and even lucrative) jobs—for a variety of reasons. If you talk to the ‘back to normal/virus is overblown’ crowd, this is a function of their getting enough government money to live on, and general indolence.

But there is another story: Americans are ditching their jobs by the millions, and retail is leading the way with the largest increase in resignations of any sector. Some 649,000 retail workers put in their notice in April, the industry’s largest one-month exodus since the Labor Department began tracking such data more than 20 years ago.

People are leaving because they discovered they liked working from home, or because they’re taking care of children or elders now, as the world is still too dangerous for Previous Normal behavior. Or the pandemic has forced them into paths (not commuting, cutting back spending) they’re planning to maintain.

They have re-balanced their personal values, decided that life is, indeed, too short to waste doing junk work.

You can see this as bad for business, particularly the service industry. Or you can see this as economic optimism—the chance for a fresh re-start: One general theory is that we’re living through a fundamental shift in the relationship between employees and bosses that could have profound implications for the future of work.

This applies to education, too—a field generally marked by stable but low-wage, high-skill work done primarily by women. We’ve been experiencing a long-term decline in teacher preparation, nationally, a drop of 67% in Michigan. Those classrooms we’re hoping to fill this fall? Not enough teachers.

Or school leaders.

Veteran educators are used to charter operators and superintendents–like LA’s Austin Beutner–discovering that running a school, a classroom, or a large urban district is not all apples and playgrounds. Beutner’s observation–“We are humans. We have families. We have partners, spouses, kids, our own life responsibilities. For better or worse, schools become a magnet for all of the challenges which face society. . .”—is the story of their working lives, for decades, not a trial period as CEO.

What is interesting to me is the anecdotal evidence coming out of the news about schools, their leaders focusing on what’s good for students—the core of their work—rather than what the legislature or governor thinks students need.

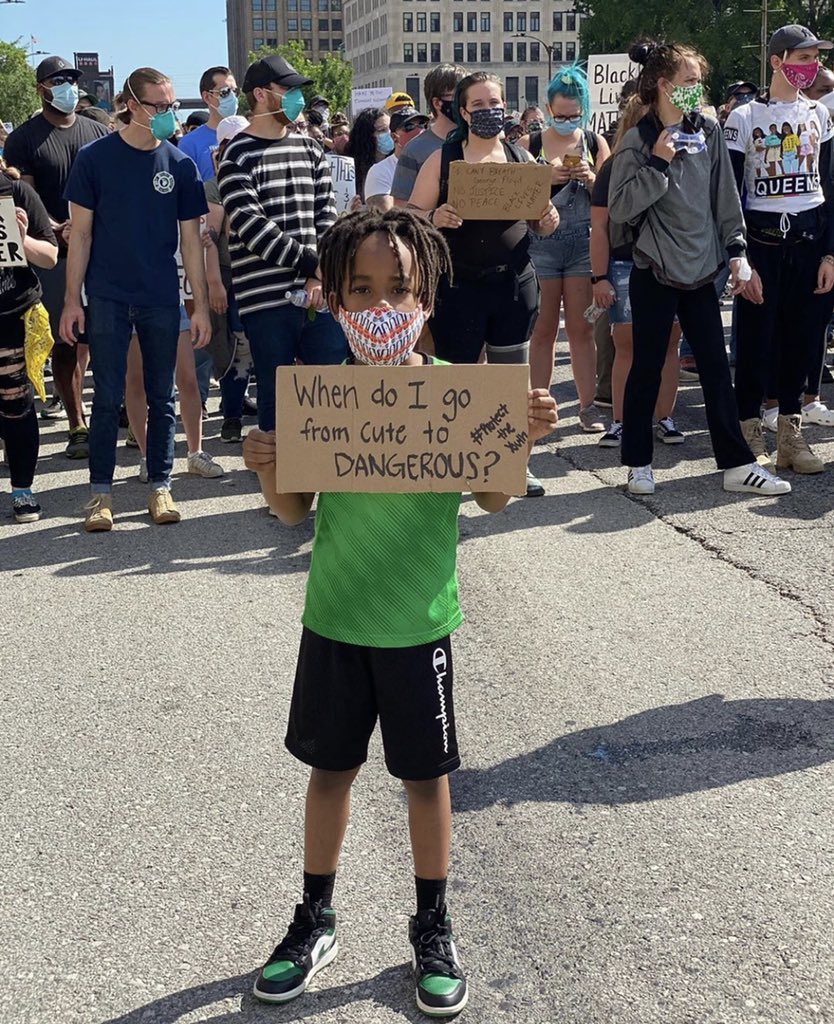

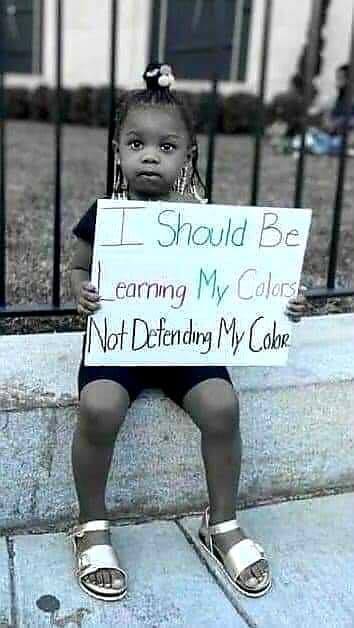

There’s the whole Critical Race Theory divide, for starters. Go ahead—tell us what we can and can’t teach, including the truth about our own history.

There’s the re-born #OptOut movement.

But there’s more: virtually every Michigan school has decided to go around legislation that requires them to flunk third graders who are not testing at grade level in reading. Bridge Magazine calls this a ‘revolt’– but superintendents and teachers just laughed at legislators trying to move the mandated flunking up to 4th grade. This is akin to soldiers returning from blood-soaked battlefields, informing the generals that their orders are crazy-pants, not gonna work.

And when Michigan’s Chief Doc of Health and Human Services recommended that students be masked when they return to school in the fall, and got pushback from Great Lakes Education Project, a school choice group founded by Betsy DeVos? The recommendation was met with a shrug by school officials, who plan to make their own decisions about whether students will wear masks this fall.

As they should.

If the pandemic has revealed anything about public education, it’s that K-12 schooling is an integral part of the economic engine, and the good parts of Previous Normal will not return until the kids are back in school, 180 days a year.

Who will solve the problems created by the Great Reallocation of talent in K-12 education?

Hate to sound like the eternal broken record here, but shouldn’t we turn to educators—school leaders and teachers, working in their own unique context, to advocate for what their kids need? Better connectivity and technology. Wraparound services for students. A rebuilt teacher pipeline. A little TLC after surviving a pandemic. Better salaries and benefits.

Autonomy.