Back in the day, when I was an early-career teacher, I was sitting at the judges’ lunch table, at a music festival. It was my first time serving as an adjudicator and the other judges were well-known veteran band directors. One of them was expounding on the poor literature choices made by young band directors. He claimed that identifying quality music was becoming a lost art, and that most newly published band music was ‘trash,’ especially compared to the pieces from the early days of school band programs.

It was out of my mouth before I had time to think: What is ‘quality’ music? How do we know it’s worthy?

His answer was mostly eye-rolling at the other men and sputtering—but he ended by saying that his sainted mother used to listen to country music on the radio, and even as a young lad he knew that it was pure garbage. Nobody was correcting him, by the way. Certainly not me.

I did, however, start thinking more about my own judgment in deciding what music would teach my students the most. I looked for appealing pieces that had some modest challenges embedded. I made some mistakes (buying pieces that were so static and repetitive that even the students were able to see how some music is, well, static and repetitive—and boring). But I also picked some winners, pieces I used again and again, music with some cultural depth or technical tests or simply tunes that the kids loved.

Were my curricular go-tos ‘quality’ music? What features, precisely, comprise quality? Is there a set canon of high-quality titles that should be in every library?

And–who gets to say what those works are, in any discipline? Choosing the best anything is a perennial exercise in taste and appraisal—and over time, the definition of ‘quality’ shifts.

English teachers want their students to read and interact with the most delicious texts. Social Studies teachers want to wrestle with relevant issues and science teachers want to engage their students with scientific solutions to existing real-world problems. What’s most useful and attractive now may not have existed 10 years ago.

I trust teachers to sieve through the Big Ideas and choose good concepts and materials. That’s not possible in many schools, however, where all curricular decisions are made above (if that’s the correct preposition) the classroom. Replacing materials also costs money.

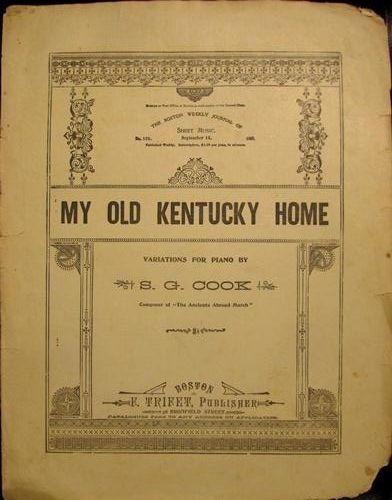

There was a piece in Medium recently that got some deserved attention: Dinah, Put Down Your Horn: Blackface Minstrel Songs Don’t Belong in Music Class. The gist? We need to take a look at the often-racist roots of some American ‘folk music.’

I read about the piece on an Elementary Music Teachers Facebook page. There was a long thread, discussing music that might have problematic origins. Were there ways to get around questionable lyrics while keeping a jaunty, familiar tune? There was a little disagreement—a couple of people upset by ‘political correctness’—but the large majority of the teachers participating thought the article had value in helping them improve their practice by ditching some songs long considered ‘classic.’

Many admitted that all this information was new—and surprising—to them; they could do better. There were comments about high school and college traditional/fight songs with racist roots or references.

I loved reading these conversations. These are questions that teachers should be discussing. Teachers are conscientious for the most part—they want to teach well. They will even occasionally be vulnerable, confessing that they don’t know how to handle a curriculum/instructional dilemma. This discourse supports genuine professional learning.

For music teachers, the next frontier might well be the dearth of music published for school musicians with female or non-white composers.

Composer Dale Trumbore said this: Let’s talk about quality.

‘I program music based solely on quality.’ ‘I don’t think about race or gender when I program—only whether the music is good.’

This argument is fundamentally flawed. You’re programming based on the quality of music you’ve already heard. If you don’t regularly hear or seek out music by women or composers who aren’t white, their music will never make on to your programs. Lack of quality isn’t the issue here; unconscious programming is.

Is this a key issue for music teachers? It should be. For a dozen reasons—including our old benchmark: quality.

Recently, there was a revelation that a very well-known school band composer, a white man, had been publishing Asian-flavored pieces using a pseudonym that suggested he was a Japanese female. Eventually, he started feeling a bit queasy about the deception (or perhaps his publisher got tired of not having any PR information about ‘Keiko Yamada’). He publicly apologized and recalled all the inventory using his phony name.

The composer, Larry Clark, sat for a long and somewhat rambling interview with Jennifer Jolley, another female composer, explaining, sort of, why he originally chose to use a pseudonym. He is not entirely successful in this effort, although I am certain he now regrets the initial decision. Jolley holds his feet to the fire—it’s a wonderful, in-depth interview. Then she says:

The lingering effects of Clark/Yamada are to magnify the paranoia and cynicism too often experienced by underrepresented composers. It confirms the most extreme sense that the music world is an unfair system rigged in favor of the privileged.

I think teachers of all subjects are interested in concepts and materials that show their students the system doesn’t have to be rigged in favor of the privileged—that there are things we all should know and can all appreciate. That curricular materials in all subjects can be authentic and inspiring.

I think I know quality materials when I hear and see them. I also think that our definition of curricular quality has to consider diversity and acknowledge change. Some items are evergreen. Others outlive their usefulness.

How do you define quality?

It’s a little beside the point, but I rue the effect of adjudication and competition on modern band composing. You can just see the composer sitting there ticking off items on the This Will Help The Band Show Its Awesomeness checklist– key change, counting challenge, pulse shift. It’s like composing by numbers, and it makes me crazy.

LikeLike

You are speaking my language, friend. I started my teaching career keen on building a dynastic band program where we aced competition after competition. That lunch I mentioned early in the blog? I was determined, back then, to be a perennial ‘winner’ via being a hard-ass. I was trying to soak up all the hard-assness of the other band directors, plus their accrued wisdom about sure-fire festival music picks.

I have actually gone to workshops sponsored by my state musical organization, where presenters openly say ‘I would never program this on my spring concert, because it’s trite, but it’s a great festival piece.’ Then they pass out a list of other sappy contest pieces that don’t push kids at all, and leave us bored.

It took a long time for me to stop being a band director and start being a music teacher. The first step was choosing not to go to festival. There were many reasons not to go, including the practice of devoting six weeks to ‘cleaning’ blah music. I had over 300 kids in the band program, in 4 performing groups. With the cost of buses, extra scores for judges (12 pieces, 3 scores each), entry fees, plaques, and so on, the cost of going to festival was three times my annual band budget.

I think the turning point was getting my comment sheet back, and the first thing I read is; “Your students do not have uniform footwear! Distracting!” Yup. I paid hundreds of dollars to read that.

LikeLike