When I was in third grade, I contracted the mumps. This was my final act in the 50’s-Kid Illness Trifecta: measles, chicken pox, mumps. Back then, pre-vaccine, this was considered No Big Deal. Polio was the thing to worry about—it was a killer. I had a cousin die, at age two, from polio, but nobody knew anyone who lost their life from the mumps.

Unfortunately, however, I developed encephalitis—a brain inflammation—from mumps. I don’t have a lot of information about how the illness was diagnosed or treated; my mother, who would have been the keeper of that knowledge, is long gone. I only know that I was out of school for nearly two months.

I have these distinct 8-year old kid memories: Going to the hospital for tests. Needle pokes. Terrible headaches and keeping my face covered by a towel. Bitter blue pills that I took in applesauce. And lying in bed, alone, for weeks on end, as winter turned into spring.

When I returned to school, I was sent for achievement testing. This was not to find out how far I’d fallen behind, but because all the other third graders had taken the test while I was absent. I was pulled out of class and given the test by a different teacher.

When I finished, she took a pencil and skimmed through the answer sheet. You’re a very smart little girl, she said. This made me incredibly happy–and is undoubtedly the reason why I remember a random remark made 60 years ago. Nobody in my family had ever called me smart. In fact, my mother worried because I spent too much time in the house, with my ‘nose in a book.’

And nobody, as far as I can tell, was stressed about how far behind I may have fallen. Kids got sick, they came back to school, teachers tried to catch them up. Sometimes they zoomed forward. Other times, not. Because that’s what learning was like—sometimes fast, sometimes slower. No big deal.

I read today that Australia has decided that when schools re-open, school attendance will be at parents’ discretion. Those parents who are able to work from home have the option of keeping their children home and using school-provided on-line resources. Parents who are essential workers and have out-of-home jobs to return to may send their children back to bricks-and-mortar schools.

My first thought was that schooling is hard enough when all the kids are there, or all the kids are remote. Expecting schools to smoothly adapt to a bifurcated instructional plan is probably another step toward outright chaos in public education. Leaving us even more vulnerable to astro-turf ‘Commissions’ like these people, waiting in the wings to scoop up funding and ‘create (profitable) solutions.’

My second thought was that hybrid home instruction/physical school might well happen here. We are, at the very least, a year and half away from a world where children are not only themselves safe from a virus, but unlikely to become adorable little vectors.

For all the good—and real—conversations about how invaluable school is in our national social and economic organization, there has been no solid, easily adopted plan for re-starting public education. We may end up with something that looks quite different at first, and we may morph—for much better or far worse—into a completely altered conception of how ‘school’ works.

Here’s an example: A friend posted the suggestion that students return to school in the classroom they were in when formal school ended, in March. That would, she argued, preserve teacher knowledge about students’ strengths and weaknesses and allow the most tailored, individualized instruction.

Immediately, her elementary-school colleagues started raising ‘buts’—but who will teach the new kindergartners? But what will the 7th grade receiving teachers do—will middle school also have to stay at the same level with the same teachers? But what about seniors? But I don’t want to teach the next-grade curriculum!

All of these arguments are based on the idea that all important knowledge and skills can be divided into thirteen neat slices and all students should encounter, engage with and even master these slices, in order, based on their age, before they can successfully navigate to the next grade or higher education or the world of work.

Which is ludicrous. Everyone—and especially teachers—knows this is absurd.

Countless articles and books, and reams of scholarly research have confirmed this inescapable fact, which seems to have been the common (and accepted) wisdom when I was in third grade, 60 years ago: Kids learn at different rates, and those rates are variable throughout any school year or other formal period of learning. Also, they’re better at learning some things than others. That’s just the way it is. Do your best to move them forward.

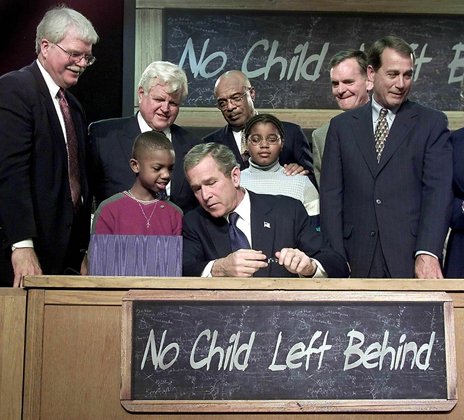

Which leads to this question: How did we get to the point where everyone in the country agreed that certainly no child should be left behind—and then spend billions of dollars trying to precisely define what ‘left behind’ means, using questionable tests and multiple linear regressions?

If there is one good thing that comes out of this pandemic, in terms of public education, it might be an agreement that all children are potentially being ‘left behind,’ right now, in mastering ‘grade level’ concepts. So pricey common core curricula and the expensive standardized tests they support can be acknowledged as useless for the next few years, and perhaps forever.

Creative, compassionate teaching, hybrid schools, flexible schedules and a focus on needs-based, rather than standardized, learning might actually catch on. And we wouldn’t ever have to label a child as ‘left behind’ again.

I’m retired, so perhaps I don’t have a right to weigh in on how to move forward because I’ve been spared trying to do school remotely.

Nonetheless, I think the smoothest route to resuming classes might be to have kids and teachers return to the same classrooms they left so hastily, exempting seniors at high school. Give the folks who know the students best a chance to put eyes on the kids, assess the damage caused to individuals in terms of their personal experiences (not academics), and figure out who is most in need of which supports. Those are things teachers do all the time. Pick up academically where folks left off, integrating concepts and content shared virtually. Then, maybe in November or January, everyone moves ahead to a shortened SY 2020-21. Kindergartners begin class too.

Getting rid of testing and test prepping will salvage about 6 weeks of school time, and could be the death knell for expensive, useless tests. Use the unspent funds with two goals:

1. to reduce class sizes for 2020-21 in order to accelerate the pace of instruction, and

2. to bring in extra support personnel to heal the trauma, especially in our hardest hit locations.

We’re going to have to rebuild this. Let’s do it well, keeping the kids’ needs foremost.

LikeLike

Hi Christine. Thanks for your good comment–and I want to heartily confirm the right of every retired teacher (like you and I) to express their opinions. I, too, was attracted to the thought of kids returning to their teacher(s) of record last year, then moving on to new classrooms, once the teacher who knew them could see them, and teach them, doing an informed evaluation of what’s OK and what’s critically missing or needing to be addressed. And also (no small thing)–provide some comfort and stability. (Notice I didn’t say closure.)

In fact, I was surprised that so many teachers could not imagine that happening, and launched right into ‘but what about…’ The main pushback seemed to be not wanting to teach any content from the next grade. In fact, that’s what made me think about writing the piece–that ‘OMG! Does that mean I’d have to teach fractions?!?’ response.

I didn’t write that in the piece, because I’m of the opinion that too many people are punching down on teachers who already have WAY too many people telling them how to do their jobs at the moment. But it also made me worry that our sense of imagination, as a profession, has been flattened by so many standards and tests and stressors. Would teachers welcome their 2020 classes back into their classrooms for a few months, if they didn’t have to worry about state tests and will the 3rd graders fail if they can’t read, yada yada–I have to think they would.

Nancy

LikeLike

Our profession is suffering from 25 years of reformsterism. When China decided to take over Tibet, they began by moving ethnic Han into Tibetan villages, gradually eroding culture, language and traditional practices. That’s what has happened in teaching, too. This was brought home for me at a meeting of my union’s committee on Less Testing, More Learning. A few minutes into our initial meeting, a young teacher interrupted to ask, but isn’t our job to get the kids to pass the tests? She herself had grown up in the testing era, so perhaps it seemed logical.

For me, a return to school must be a moment where we put Maslow before Bloom. Educating kids means first attending to their emotional health so that we can then, second, instruct them in content areas. Teachers must assert their professional authority at this difficult time and insist that we, not the privatizers, test companies, and reformsters, know how best to help our kids.

LikeLike

It’s teachers who are too fearful to assert their professional authority I worry about–and those like the teacher who asked if it was our job to focus on tests.

Last year, I was an e-mentor for a young teacher getting a masters degree in teacher leadership from a prestigious university in an eastern state. It was kind of a cool program–teachers from around the country e-meeting weekly with masters candidates working on their capstone projects. The teacher I was assigned was enthusiastic and wanted very much to be a teacher leader.

The first time we met, she was supposed to have an outline of her capstone leadership project. The theory was that we’d have an hour-long conversation weekly, and I could suggest resources, poke at her ideas, read drafts, and so on. Her self-designed project was around getting teachers in her building to be more informed and enthusiastic about the state test (she taught MS English). She’d been sent to several workshops and conferences around data analysis and wanted to share this knowledge with the other teachers.

In the end, she shifted the project, a bit, toward assessment literacy, but was caught between what her administrator wanted her to do (as a formal ‘teacher leader’) and what the rest of the staff thought about their own ability to assess students and use that information to shape instruction.

I had the same thought as you–testing is all she’s ever known. She did well on tests herself, and sincerely wanted kids to do well on tests. Because that’s our product now–test scores. I felt crestfallen after almost every conversation.

LikeLike

[…] There also should be an emphasis on reassuring parents that learning is still going on despite schools being closed. Education writer and former teacher Nancy Flanigan tells the story of missing several months of formal schooling as a young child due to the mumps. […]

LikeLike

[…] Every Child Left Behind […]

LikeLike