A bit of personal history: I live in the first state to launch statewide standardized assessments, back in 1969-70. Every single one of the 32+ years I taught, in every school, at least some of my Michigan students were taking state-sponsored standardized tests. Honestly, I didn’t think about it much.

In the 1970s, we had the MEAP test for 4th, 7th and 10th grades—two to three days’ worth of testing blocks, in the fall. Teachers understood they were tests of basic skills, and the best strategy was simply reviewing traditional concepts. A couple of times, one of the elementary schools in the district where I taught had a 100% pass rate. Because, on the MEAPs, students either did well enough to meet the grade-level benchmark, or they didn’t.

Schools with low pass rates got more money. The state legislature thought more intensive instruction would help children whose critical skills were weak. For the rest, well—the annual check-up was over.

Those were the days.

What this means is that Michigan stands as the first state to have 50 years of testing data, from a wide array of tests. We had state-created tests, aligned with state-crafted standards. For a while, all our juniors took the ACT, whether they were college-bound or not. We’ve used our own, written-by-MI-teacher standards and common standards. We implemented a rigorous, college-bound “merit” curriculum for all, in the hopes that it would raise test scores.

We had cutting-edge hands-on 8th grade science tests, performed in lab groups, where teams of students caused a tubular balloon stretched over a narrow beaker to inflate and deflate, as the gasses inside heated and cooled. That one was fun.

What we haven’t had is clear and steady improvement in test scores. In fact, due largely to clear and steady reductions in funding, we’ve slipped to near the bottom of the pack.

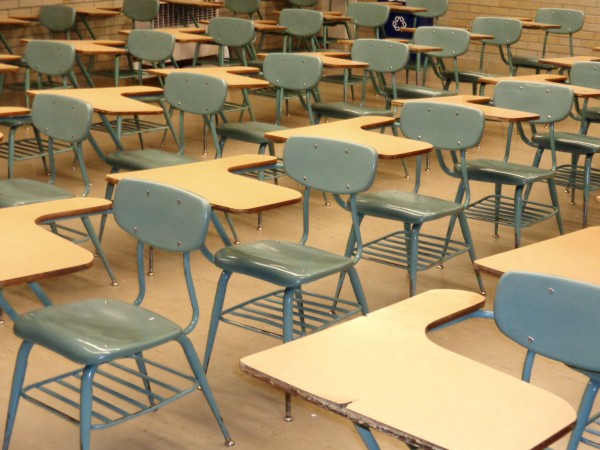

And now, we have students taking computer-based tests at home. In front of their parents. Leaving aside the very real aspect of invalid data, parents are observing, in real time, the testing process. A friend got this message from one of her former students, now a parent herself:

Just had to share how horrified I am by the NWEA tests. Our school this year is allowing us to take them from home and today [my second grader] took the reading and math assessments. He was immediately discouraged by the math (his favorite subject) as the first few questions were things he hasn’t been exposed to yet. This set him up to fail on questions he could answer because he was upset and “feeling stupid”. I can’t imagine what it must feel like to have to proctor these assessments for a group of kids and have your own success as an educator be judged by the results of these awful exams.

Thank you for being such a strong voice advocating for all of our kids and for educating educators. I’m so grateful for the amazing teachers I was blessed with all throughout my time at XX and for the fantastic educators my kids have had thus far too! Are there places or people that would be helpful to contact or to share our experience with, in order to help propel change?

The ‘strong voice advocating for all our kids’ this mom is addressing is June Teisan, a nationally recognized teacher leader. And while the thrust of the comment—I had no idea how damaging these tests could be until I saw them for myself!—is more and more common, it’s the last sentence that sets it apart.

Just who needs to know about this? What can parents do?

The Opt-Out movement is still alive, and parents have more reason than ever to reject standardized tests. But this may well be our window for changing, once and for all, our pointless and wasteful love affair with standardized testing. They don’t tell us what we need to know, and they harm kids who don’t deserve harm. It’s as simple as that.

Ask any teacher: What are the real outcomes of using standardized testing? Cui bono?

The scariest thing to me is that any teacher who’s joined the profession in the last 15-20 years is thoroughly familiar with The Tests, and may in fact see them as something we’ve always done, something necessary. Something, without which, we will be flying blind. They might perceive school as a place where all decisions are best made off-site by ‘experts’ and ‘authorities,’ without whom there would be no ‘accountability.’ A lawless place that needs plenty of guardrails and consequences.

It wasn’t always like this.

June and I had a short conversation about this—who might be able to help parents, teachers and school leaders assemble the strength to buck the corporate test-makers and non-profits? Those who depend on the data generated by tests to make proclamations and influence policy-making?

There are always new reports and opinion pieces on testing to share. Tom Ultican has a good one where he says this, about CREDO’s scare-mongering over projected (not real) falling scores:

This is the apparent purpose of the paper; selling testing. People are starting to realize standardized testing is a complete fraud; a waste of time, resources and money. The only useful purpose ever for this kind of testing was as a fraudulent means to claim public schools were failing and must be privatized.

Bob Shepherd, a retired teacher with long experience in the industry says this:

The dirty secret of the standardized testing industry is the breathtakingly low quality of the tests themselves. I worked in the educational publishing industry at very high levels for more than twenty years. I have produced materials for all the major standardized test publishers, and I know from experience that quality control processes in that industry have dropped to such low levels that the tests, these days, are typically extraordinarily sloppy and neither reliable nor valid.

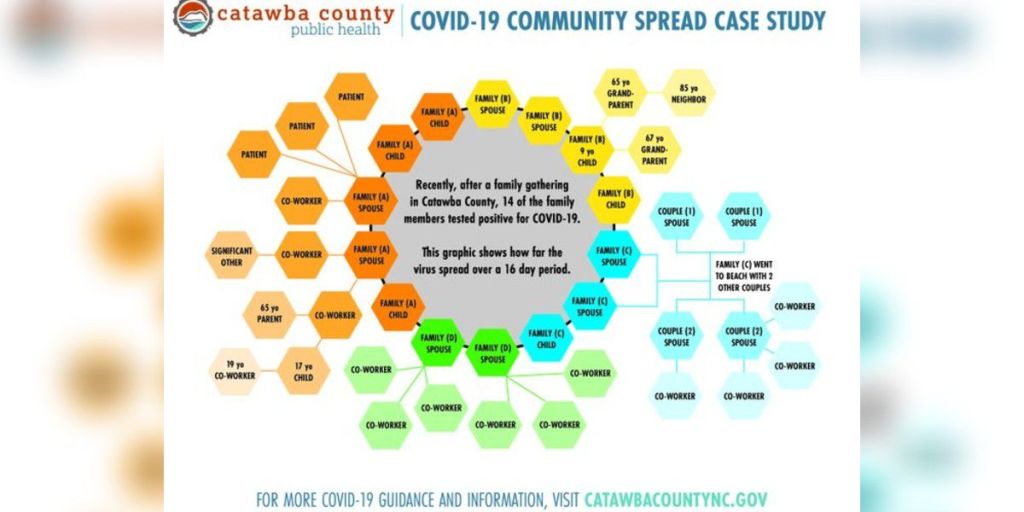

The series correctly concludes that state accountability systems have not improved student achievement or closed achievement gaps over the last decade. Despite this conclusion, however, the series puzzlingly insists that state testing and accountability systems must be reinstated in 2020-21 and must focus on schools with the lowest performance levels.

Reports overstate some research conclusions and ignore a large body of research about factors that influence student outcomes. Specifically, the reports do not acknowledge the critical need for access to quality educators and fiscal resources, which are foundational to any serious effort to improve student outcomes. Moreover, the reports focus very narrowly on test scores as the primary outcome of schooling and ignore outcomes such as critical thinking, media literacy, and civics that are more important than ever.

If there were ever a time when testing ought to be suspended, re-examined and scaled back, it’s now.

Why scaling back and not eliminating them, cold turkey? Because I’ve been on this earth long enough to know that it’s not likely that grant-funded education nonprofits and test manufacturers will go down without a fight.

And try explaining to any forty-year old college-educated Dad that tests don’t matter any more, his children don’t have to take them, and every teacher will just be trusted to do their best from now on.

Ideas like ‘accountability’ have seeped into our national consciousness. Fear of ‘falling behind’ has been the subject of any number of local news stories. And let’s not even start with the beating teachers have taken, during a pandemic, when the idea of neat and tidy, leveled learning goals turned into flaming Zambonis.

We’re not getting rid of tests that easily. However.

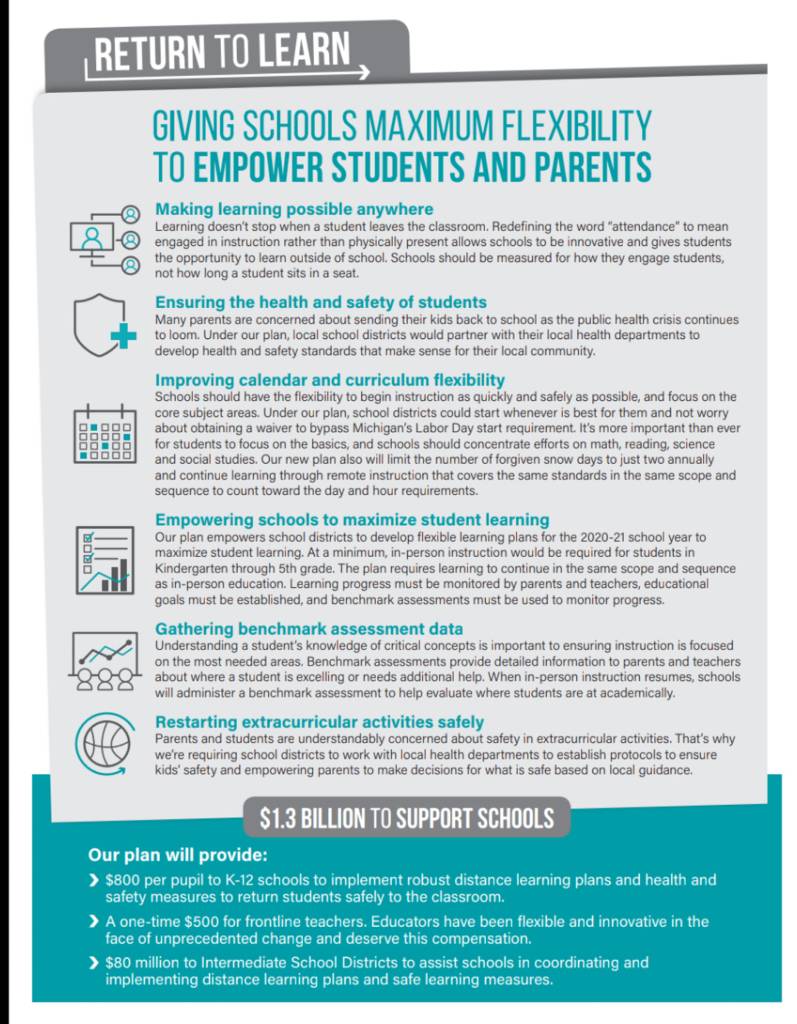

Now is the perfect time for school leaders to strip off expensive unnecessary standardized tests, using budget crises and lack of technological infrastructure as an excuse. It might be time to put a focus on critical thinking, media literacy and civics, rather than drilling on testable items. Time to support parents who want to opt their children out.

For fifty years, Michigan has been testing, testing, testing. It’s time for a re-think. And it’s time for parents to turn to teachers and school leaders and demand change.