It was the most prosaic of news items: a local township planning commission working on a new master plan. They secured a skilled, experienced civic planner who provided a draft, which included (as all good municipal documents do) a brief analysis of the township’s demographics: “94.7 percent of the population reported as white, 2.6 percent of the population as American Indian/Alaskan Natives, 0.2 percent reported as black or African American, and 2.5 percent as Hispanic or Latino.”

Which drew this response from a member of the planning commission:

“I’m opposed to this whole color issue. In my opinion, you’re either a citizen, or you’re not a citizen. And with this government listing everybody by their color, that’s the government and the media promoting racism. I would suggest we make a comment [in the master plan], something to the effect that we have…a diverse community.”

The planning expert: “Well, you don’t. You’ve got a 94.7 percent white [population].”

It went downhill from there—rapidly—and ended up with the hired expert and another member of the planning commission resigning, and a third commissioner stating that the ‘race thing’ in the plan was ridiculous, and oh, by the way, his brother-in-law was Black.

I share this (stupid) story for all the school districts and teachers that feel that they have been unfairly targeted by what seems to be one of our ‘new normals’—rampant, unhinged intolerance.

In other words, teachers and conscientious school leaders, it’s not you—or just you. It’s racism. Or homophobia, or xenophobia.

It’s ignorance. The problem that never goes away—and society expects public educators to solve, somehow, without ticking off parents.

You may have, to your surprise, become the enemy (after two grinding years of serving children and families during a global pandemic), for simply teaching facts and showing compassion and commitment to your students. But you’re not alone. And this is not new.

These anti-truth, anti-education campaigns come and go, in waves. Disinformation and blind opposition and noisy meetings have always been part of government-provided services.

The world is currently witnessing a devastating, lethal master class in international propaganda in Ukraine. Who will tell the truth to our students? Not TikTok. When civic authorities assert that a 95% white township is a ‘diverse community,’ someone needs to speak up for the truth.

In a spectacularly good article in The New Yorker, Why the School Wars Still Rage, Jill LePore traces the history of this power struggle in American public education, using the Scopes trial as long-term case study:

In the nineteen-twenties, the curriculum in question was biology; in the twenty-twenties, it’s history. Both conflicts followed a global pandemic and fights over public education that pitted the rights of parents against the power of the state. It’s not clear who’ll win this time. It’s not even clear who won last time. But the distinction between these two moments is less than it seems: what was once contested as a matter of biology—can people change?—has come to be contested as a matter of history. Still, this fight isn’t really about history. It’s about political power. Conservatives believe they can win midterm elections, and maybe even the Presidency, by whipping up a frenzy about “parents’ rights,” and many are also in it for another long game, a hundred years’ war: the campaign against public education.

LePore ranges widely, sharing plenty of negative, even frightening, examples of the aforementioned American ignorance now being codified into law (as well as cautionary language for elites who feel their progressive views about raising children automatically trump those of conservative and evangelical parents).

She also makes the point that Black intellectuals immediately understood that bills to prevent the teaching of evolution weren’t really about the theory of change in biology, something that is evident to any farmer. It was about the idea that we all spring from common ancestors, that there is no real difference between human races. That’s what really scared folks in the South, some 55 years after the Civil War.

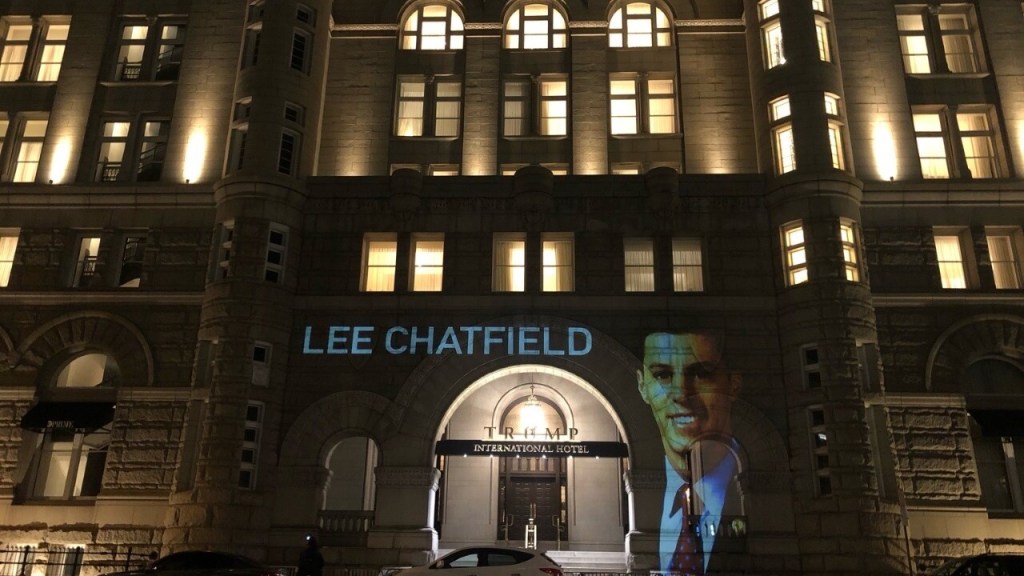

It’s easy to feel discouraged. In Whitewater Township—where the planning commissioners think they have a ‘diverse’ community—60.9 percent of the voters chose Donald Trump in 2020. Presumably, some 40 percent of those believe he actually won the election, if national survey data holds in this tiny, nearly all-white enclave.

Which is why we have to take a deep breath—as educators and citizens—and keep telling the truth.

Because the truth will set us free. Although it may take a long, long time.

Here’s a great story from Jennifer Berkshire to hearten those of you who feel that Truth no longer matters, that the anti-public education crowd, the Moms for Faux Liberty, are winning. Tag line: An upset victory last week in a red state suggests that the Republican Party’s game plan for attacking public education may not be a winning strategy.

The red state? New Hampshire, where 93.1 percent of the population is white.

Have faith.