When I was in third grade, I contracted the mumps. This was my final act in the 50’s-Kid Illness Trifecta: measles, chicken pox, mumps. Back then, pre-vaccine, this was considered No Big Deal. Polio was the thing to worry about—it was a killer. I had a cousin die, at age two, from polio, but nobody knew anyone who lost their life from the mumps.

Unfortunately, however, I developed encephalitis—a brain inflammation—from mumps. I don’t have a lot of information about how the illness was diagnosed or treated; my mother, who would have been the keeper of that knowledge, is long gone. I only know that I was out of school for nearly two months.

I have these distinct 8-year old kid memories: Going to the hospital for tests. Needle pokes. Terrible headaches and keeping my face covered by a towel. Bitter blue pills that I took in applesauce. And lying in bed, alone, for weeks on end, as winter turned into spring.

When I returned to school, I was sent for achievement testing. This was not to find out how far I’d fallen behind, but because all the other third graders had taken the test while I was absent. I was pulled out of class and given the test by a different teacher.

When I finished, she took a pencil and skimmed through the answer sheet. You’re a very smart little girl, she said. This made me incredibly happy–and is undoubtedly the reason why I remember a random remark made 60 years ago. Nobody in my family had ever called me smart. In fact, my mother worried because I spent too much time in the house, with my ‘nose in a book.’

And nobody, as far as I can tell, was stressed about how far behind I may have fallen. Kids got sick, they came back to school, teachers tried to catch them up. Sometimes they zoomed forward. Other times, not. Because that’s what learning was like—sometimes fast, sometimes slower. No big deal.

I read today that Australia has decided that when schools re-open, school attendance will be at parents’ discretion. Those parents who are able to work from home have the option of keeping their children home and using school-provided on-line resources. Parents who are essential workers and have out-of-home jobs to return to may send their children back to bricks-and-mortar schools.

My first thought was that schooling is hard enough when all the kids are there, or all the kids are remote. Expecting schools to smoothly adapt to a bifurcated instructional plan is probably another step toward outright chaos in public education. Leaving us even more vulnerable to astro-turf ‘Commissions’ like these people, waiting in the wings to scoop up funding and ‘create (profitable) solutions.’

My second thought was that hybrid home instruction/physical school might well happen here. We are, at the very least, a year and half away from a world where children are not only themselves safe from a virus, but unlikely to become adorable little vectors.

For all the good—and real—conversations about how invaluable school is in our national social and economic organization, there has been no solid, easily adopted plan for re-starting public education. We may end up with something that looks quite different at first, and we may morph—for much better or far worse—into a completely altered conception of how ‘school’ works.

Here’s an example: A friend posted the suggestion that students return to school in the classroom they were in when formal school ended, in March. That would, she argued, preserve teacher knowledge about students’ strengths and weaknesses and allow the most tailored, individualized instruction.

Immediately, her elementary-school colleagues started raising ‘buts’—but who will teach the new kindergartners? But what will the 7th grade receiving teachers do—will middle school also have to stay at the same level with the same teachers? But what about seniors? But I don’t want to teach the next-grade curriculum!

All of these arguments are based on the idea that all important knowledge and skills can be divided into thirteen neat slices and all students should encounter, engage with and even master these slices, in order, based on their age, before they can successfully navigate to the next grade or higher education or the world of work.

Which is ludicrous. Everyone—and especially teachers—knows this is absurd.

Countless articles and books, and reams of scholarly research have confirmed this inescapable fact, which seems to have been the common (and accepted) wisdom when I was in third grade, 60 years ago: Kids learn at different rates, and those rates are variable throughout any school year or other formal period of learning. Also, they’re better at learning some things than others. That’s just the way it is. Do your best to move them forward.

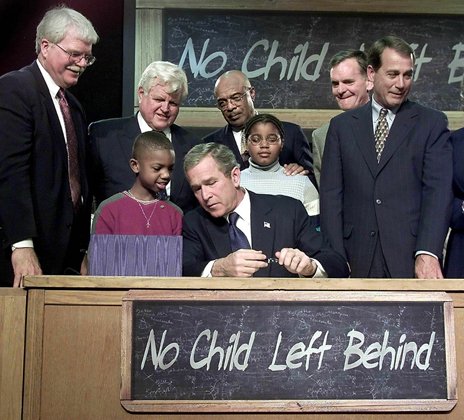

Which leads to this question: How did we get to the point where everyone in the country agreed that certainly no child should be left behind—and then spend billions of dollars trying to precisely define what ‘left behind’ means, using questionable tests and multiple linear regressions?

If there is one good thing that comes out of this pandemic, in terms of public education, it might be an agreement that all children are potentially being ‘left behind,’ right now, in mastering ‘grade level’ concepts. So pricey common core curricula and the expensive standardized tests they support can be acknowledged as useless for the next few years, and perhaps forever.

Creative, compassionate teaching, hybrid schools, flexible schedules and a focus on needs-based, rather than standardized, learning might actually catch on. And we wouldn’t ever have to label a child as ‘left behind’ again.

![Attachment-1[21553]](https://teacherinastrangeland.blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/attachment-121553.jpeg?w=730)