When educators talk about the Reading Wars, they’re not overexaggerating.

With the possible exception of the similarly bitter Math Wars, there’s no pedagogical battlefield more littered with sacred-cow theories, bold statements, unsubstantiated policy and outright acrimony.

Recently, the combat has heated up again, with a handful of irate but organized parents and a spokesperson with good media connections claiming that the ‘science’ of learning to read is ‘settled.’ As if a proclamation about the One Best Way could convince the public (and, even more ridiculous, reading teachers) that if we all just calmed down and standardized reading instruction, every single child could read by the end of first grade, as God intended.

Which was why it was so refreshing to read this from Michelle Strater Gunderson, long-time first grade teacher (and articulate union leader) in the Chicago Public Schools:

It should not be expected for a child to read by the end of first grade. We should only be concerned if the process of learning to read has not yet taken hold. Please debate.

At this writing, there are 65+ comments, all of which boil down to this: No debate. The statement is true (often followed by personal examples of how this race-to-read pressure has done great damage to children).

I have waded into the reading instruction controversy a couple of times—here and here, for example—and always drew irate observations about my lack of credibility as commenter on reading pedagogy, because I am a music teacher. What did I know about teaching kids to read?

It’s true that I am not a traditional reading teacher. Instead, I taught about 5000 (that’s not a typo) kids to read a new language–music–when they were somewhere around ten or eleven years old.

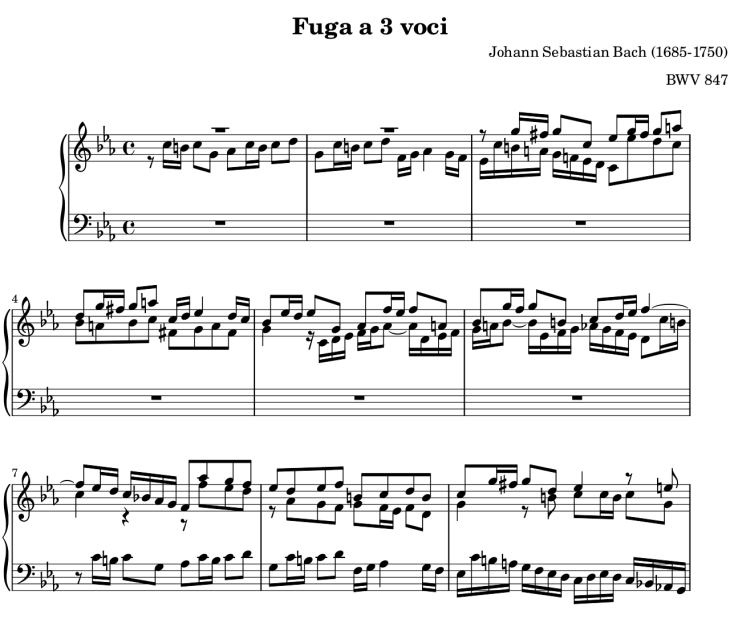

In other words, fifth or sixth graders, developmentally ready to cope with the intellectual task of interpreting symbols, putting them into musical phrases and sequences, while simultaneously thinking about fingers, embouchures and wind production, tone quality, intonation, expression, and reading at a fixed rate. It’s a very complex process, as difficult as phonic awareness, combining sounds into words, and then making meaning.

I did all this in very large, less-than-ideal mixed-instrument (and mixed ‘ability’) groupings, often as many as 50 students in a class. I need to stress here that I am nothing special, in music-teacher world– secondary band, orchestra and choral teachers do this all the time.

Yes, some students come to us with previous experience as music readers, just as some students come to kindergarten already having a fair grasp of decoding and a healthy vocabulary of sight words. Music students may also have developed unhelpful music-reading habits (inability to keep a steady beat, for example, which plays havoc with group instruction). Other students come to the process of learning to read music as ‘failed’ traditional readers, but end up becoming valuable members of our musical groups, because of the adaptation skills they have developed—watching and listening for cues that aren’t apparent to them through visual symbolic interpretation.

I was able to teach kids across a wide spectrum to read music because:

- My students, at age 10 and above, were developmentally ready for the knowledge work, the interpretation of representative symbols—in current ‘reading expert’ parlance, the ‘codes’ established in Western music.

- They were strongly motivated.

- The learning process was both challenging and fun.

- Strugglers were not singled out, but allowed to make mistakes, anonymously, for a relatively long period of time, until they perceived their own errors, asked for help, or were corrected. Nor were students grouped by any perception of their ability or talent—there were no ‘Bluebird groups’ in beginning band, where the core learning took place.

- There was little home pressure–not many parents were expecting virtuosos (or cared all that much); it was an elective and it was supposed to be a pleasurable enrichment activity.

- Learning was non-competitive.

- There were multiple modes of learning available in every single lesson: Reading accurately (visual). Watching and imitating the teacher or other players until fingers and positions or vocal production felt comfortable (kinesthetic). Listening and matching (auditory). An uncritical acceptance of mistakes as a way to learn (social acceptance), then trying again.

What amazes me is that none of this is ever considered ‘reading instruction’ or ‘the science of learning to play an instrument.’ We just collectively stumble our way through the early stages of learning to play or to sing, using every tool available, having fun while we’re at it. There are schools of thought in music instruction (just as there are in reading pedagogy), but there are no public Music Wars.

Another amazing thing: there is ample evidence that learning to play a musical instrument strengthens all of the innate skills necessary for fluent reading. (Here, and here—and there are dozens more examples in my files.) But I’ve never seen anyone suggest that it would be better to give students supplemental musical instruction when they’re labeled ‘behind’ in reading proficiency (a word I’ve come to mistrust). Instead, we take away the arts and recess, or simply force the child to repeat a grade, repeat the same ineffective reading instruction, believing humiliation is the cure.

Michelle Gunderson is right. We’re pushing too hard, too fast. And it isn’t helping—it’s making things worse.

Thank you for this excellent commentary. I have never thought of this comparison before but it makes absolute sense. Perfect sense!

I have been in many “reading war” debates and wish that this perspective would have been shared. Now, as a retired educator, I can only hope that current teachers and administrators see the value and accuracy of your enlightened thoughts.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment, Mary.

While research on effective ways to teach reading (and other subjects, for that matter) is undeniably a good and useful thing, measuring that effectiveness is tricky–do we expect instant ‘results’ or are we willing to keep teaching, careful to preserve students’ confidence in their own ability to put the intellectual tasks together and be rewarded as readers? Are we willing to acknowledge that there’s more than one way to achieve our ends? If not, we’re probably always going to be at war.

LikeLike

[…] you’ve never read education blogger and retired music teacher Nancy Flanigan’s blog Teacher in a Strange Land, you need to start. Flanigan is an excellent writer who is unafraid to wade into controversial […]

LikeLike