Had I known when I was younger what these students were sharing, I would have been liberated from a social and emotional paralysis–a paralysis that arose from never knowing enough of my own history to identify the lies I was being old: lies about what slavery was and what it did to people; lies about what came after our supposed emancipation; lies about why our country looks the way it does today. (Clint Smith)

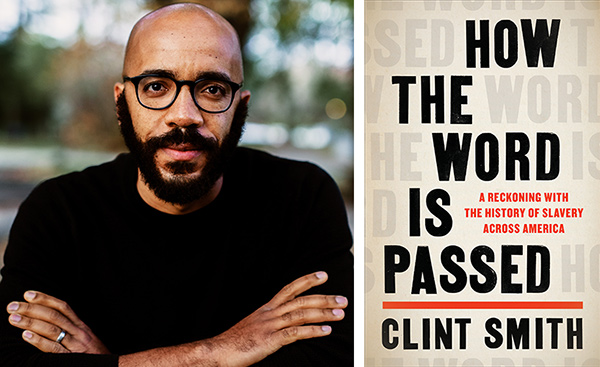

In this shocking era, when states are passing ill-advised, deceptive laws to prohibit K-12 students from knowing about the sickening, wounding realities of their own history, we truly need a book like Clint Smith’s How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America.

The students Smith is referencing, above, are performing as part of a rich Juneteenth celebration on Galveston Island, TX. They were part of a six-week summer program sponsored by the Children’s Defense Fund, designed to teach children the real story about where they live and what happened there.

Don’t all children need to know about the place they come from? Its triumphs and failures?

In the book, Smith—then a doctoral student at Harvard—visits a number of historical sites around the country that chronicle the record of slavery and its impact on every aspect of American life. He begins at Monticello, sharing his conversations with two white women in his tour group who had no idea who Sally Hemings was– the enslaved woman who gave birth to four surviving children by Thomas Jefferson. These older women, interested in ‘seeing history,’ are astonished to hear about the 600 human beings owned by the great statesman.

Each of the chapters is distinct, featuring plantations, graveyards and annual memorials. The chapter on Angola Prison, in Louisiana, is grim, beginning with its original purpose, in the Reconstruction era: to round up, then house, a low-cost workforce for plantation owners who can no longer rely on the enslaved. The chapter on New York City makes clear that nobody north of the Mason-Dixon line can claim that slavery only existed in the South.

The chapter on Goree’ Island takes us to coastal West Africa, where captured Africans were sent off to their new lives (or deaths) as enslaved workers, and includes this quote from the curator of the House of Slaves, a museum on the Island:

After the discovery of America, because of the development of sugarcane plantations, cotton, coffee, rice cultivation, they forced the [Native Americans] to work for them. And it was because the Natives died in great number that they turned to Africa, to replace the Natives with Africans.

And there it is—this is and always has been about gross economic development. How to make money off exploitive and unpaid labor of others, and the ugly rationalizations used to defend such ugly practices. And how far back this goes—long before the Middle Passage.

In a time when employers are begging for workers after a deadly pandemic (that some employers denied or downplayed), this is a particularly resonant message.

This is, indeed, the book we need now.

Smith tells us, in an Afterword, that he went to many more places than the seven he describes in great detail in this volume. That suggests that there are always places nearby—places where students have been, places they are familiar with—that can serve as testimony and memory of our local history.

As educators, it is up to us to teach that history. This is what all the anti-‘CRT’ protestors fear: the truth.

Smith illustrates that learning the truth is never divisive. It may be painful, and may produce rage—but knowing how this country was built, whose backs and hands produced the wealth and power only some of us enjoy is the cornerstone of building a more equitable society. The truth can unite us, over time. But we have to listen to each other.

Clint Smith is a published poet, and he writes like a poet and storyteller–there is lots of detail and description. Once you get past an expectation of fact-based academic writing, you begin to appreciate his nuanced depictions of people and places, the colorful, palm-strewn islands and damp, gray prison cells. Smith adds only enough data and dry content to enrich, not drown, the narration.

The book is easy to read. I read it one chapter at a time (which I recommend), pausing between to absorb and think, because each segment shares a unique perspective. Smith reiterates, in a dozen ways, that slavery didn’t start in Africa, and African-American history didn’t begin with the capture and selling of human beings.

It was a global wickedness, economically driven, but it still impacts America–the idea and the reality of America–deeply. We can’t get past it until we know the history.

Read this book.