I try, when thinking about the path this nation is currently on, not to immediately jump to worst case scenarios or inept comparisons. The uptick in the language of fascism shouldn’t be ignored, however—comparing certain people to Hitler or bemoaning the loss of democracy might not be overkill in the political soup of 2024.

It’s been sneaking up on us, like the proverbial frog in hot water. When looking at curricular change over the past five years—immediately preceding the onset of the COVID pandemic—it’s easy to see that there were plenty of precursors to the anti-woke, book-banning, teacher-punishing mess we find ourselves in as we slowly recover from that major shock to the public education system.

The scariest thing to me about the abuse teachers are taking, across the country, is its impact on curriculum. Here’s the thing: you really can’t outsource teacher judgment. You can prescribe and script and attempt to control everything that happens in the classroom, but it doesn’t work that way.

Several years ago, my school district brought in a Big Famous Ed-Presenter to do an August workshop on lesson design. Because she was expensive, surrounding districts were invited to send interested teachers, those who wanted to learn how to craft engaging lessons and units with aligned performance assessments and instructional strategies. All the teachers would be creating their own curriculum using the MI Grade Level Content Expectations—the standards documents issued by the MI Department of Education.

Once we had been seated in rounds by subject area, the presenter asked us to come up with a common, overarching topic to turn into age-appropriate instructional sequences. We at the humanities table quickly settled on ‘Core Democratic Values’ which were part of the MI Social Studies standards. We then went around the room sharing our chosen topics.

The presenter held up a hand when she heard from our table. No—you’ve misunderstood, she said. I meant something like “Westward Expansion” or “Industrial Revolution”—a topic that’s a key concept in your state Social Studies standards. We all believe in core values, of course, but this is about disciplinary content.

All the K-12 teachers in the room hastened to assure her that Core Democratic Values were indeed a key topic in the state standards, pulling up documents and published units to prove it. The presenter conceded, saying that she did this work all over the country and had not yet encountered such a broad concept—open to a range of interpretation and uses in instructional practice—anywhere in the country.

It felt like a point of pride, really, having these core democratic values as an anchor in the Mitten State standards. I’m not even a Social Studies teacher, and I could think of a dozen ways to insert the core values into lessons in the band room.

Here’s the official definition: Core democratic values are the fundamental beliefs and Constitutional principles of American society, which unite all Americans. These values are expressed in the Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution and other significant documents, speeches and writings of the nation.

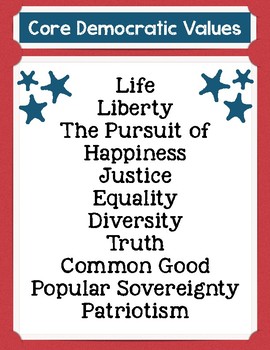

And here’s a list of those identified values: Life, liberty, pursuit of happiness, justice, the common good, equality, truth, diversity, popular sovereignty, and patriotism.

Things we all agree on, right?

Not so much, anymore.

Speaking of precursors, when Michigan was updating its Social Studies framework, back in 2018, there was a major kerfuffle over Core Democratic Values (and a bunch of other hot-topic stuff):

References to gay rights, Roe v. Wade, climate change and “core democratic values” have been stripped from Michigan’s new proposed social studies standards, and the historic role of the NAACP downplayed, through the influence of Republican state Sen. Patrick Colbeck and a cadre of conservatives who helped rewrite the standards for public school students in kindergarten through 12th grade. “They had this term in there called ‘core democratic values,'” Colbeck said. “I said, ‘Whatever we come up with has to be politically neutral, and it has to be accurate.’ I said, ‘First of all, core democratic values (is) not politically neutral.’ I’m not proposing core republican values, either.”

This wasn’t only about rhetorical confusion between ‘Democratic’—the party—vs. ‘democratic’ (the time-honored. foundational principle of our government), although that’s the first thing that comes to mind with the protestors. In fact, reading the article would be a great classroom exercise for older students. The assignment might be: Read and discuss the diversity of opinions shared here, in a representative democracy with a free press. Who should determine what students learn in a public school?

The proposed conservative edits went deep. They were about redefining concepts like equality, diversity, justice, the common good—and truth. ‘Civil rights,’ for example:

A high school standard about the expansion of civil rights and liberties for minority groups cut references to individual groups, including immigrants, people with disabilities and gays and lesbians. The new proposal includes teaching “how the expansion of rights for some groups can be viewed as an infringement of the rights and freedoms of others.” Colbeck told Bridge he added that phrase.

Surely, most public-school social studies teachers aren’t down with suggesting that not everyone deserves equity and civil rights, because granting those rights might infringe on someone else’s beliefs or “freedoms.”

After months of wrestling over these—yes—core values, the State Board adopted new Social Studies Standards in 2019. The changes they made were reasonable—you can compare the old and new. And core democratic principles and values are woven throughout the curriculum. Surprised that this story turned out OK? The battle is far from over.

The original definition and explication of core democratic values Michigan schools adopted were spot-on, nested in that most traditional American ideal: a free, high-quality fully public education for every child. One that would prepare them for active, informed citizenship. To become good neighbors, stewards of our collective environment, smart consumers and engaged voters. Community builders.

Aren’t core democratic values just about the only thing worth fighting for, in 2024?