Many years ago, in December, we were having burgers and beer in a local pub, with friends. The sound system was pumping out Burl Ives, Bing Crosby and Mariah Carey, all the ‘classic’ Christmas tunes. One of our dinner companions remarked that I must be happy, surrounded by the Christmas music he was sure I loved.

But no.

I do have a thing for Christmas music—always have, dating way back to the LPs my parents got for ‘free’ when they had their snow tires put on. (In super-snowy western Michigan, it’s either snow tires or a winter spent digging yourself out of those scary, two -story snowbanks.) The LPs featured the likes of Eugene Ormandy, Dinah Shore, Steve and Edie, maybe Elvis. A little drummer boy, a little Jesus, a little rock and roll.

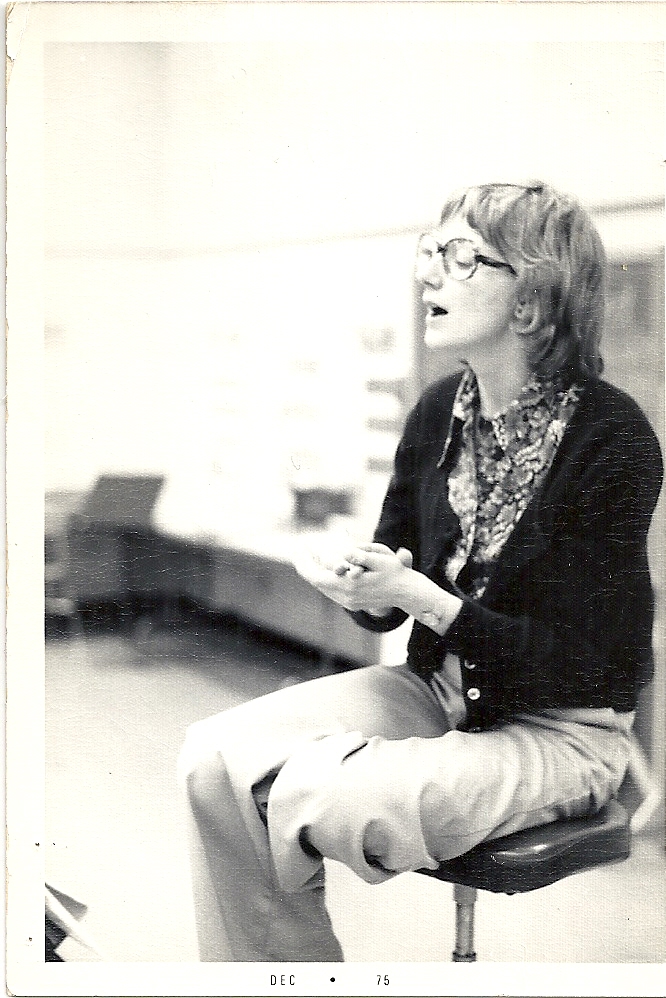

My affection for seasonal music has less to do with ‘getting in the spirit’ than seeing what artists and arrangers do with familiar tunes. Over five decades, I’ve performed in or conducted hundreds of Christmas concerts and programs, and there’s always something delicious to sing or play–and just as often, something really banal or obnoxious (lookin’ at you, Frosty the Snowman).

When I finally had my own collection of Christmas LPs and tapes, in the 1970s, I began making Christmas mix cassettes for friends, an excuse to buy more tasty holiday tunes and then turn them into gifts. Some of my long-time favorite albums—Noel by Joan Baez, arranged by Peter Schickele—stem from that period. I made one mix tape per year, and often mail-ordered LPs and tapes from esoteric catalogs or went scavenging through the bins in Ann Arbor record stores in November.

I still have one master tape made each year, beginning in 1976. Unfortunately, I don’t have anything to play them on anymore. With the advent of CDs, in the 1980s, I copied tracks from CDs and LPs on to cassettes. And when I got a computer with the capacity to burn CDs, the copying went both ways, and the buying went on, non-stop. I currently own about 350 holiday-themed CDs.

That’s right. What was once a hobby was now sort of a sickness.

When iTunes emerged, I could not imagine a more perfect way to indulge. I could buy new tunes for 99 cents while in my pajamas and cherry-pick one or two gems off my existing albums. Which I did, with all 350 CDs, yielding an ultimate iTunes cache of about 2500 Christmasy music files.

At that point, I shifted to making individually tailored CD compilations for new friends as well as long-time recipients. Some friends sent mix CDs back. All was perfect, Christmas music nirvana. Until.

Until digital streaming made CD players and iPods obsolete. And–I got a new computer, and in transferring files from the old to the new, iTunes, in its infinite wisdom, deleted all the tunes that I had copied from CDs, keeping only the new, purchased-through-iTunes files. I lost about 1500 songs. And, according to iTunes, they’re not coming back— iTunes is on its last legs, to be supplanted by Apple Music. New cars don’t even have CD players.

My annual CD-making has gone the way of Christmas cards and staying up until 2:00 a.m. to wrap gifts and assemble toys : Bye Bye.

But just this morning, a friend sent me season’s greetings, mentioning that she’s listening to a CD I made for her in 2017. Another friend said she still listens to the tape I made for her, in 1982. Right now, I’m enjoying a playlist that I made for a friend who had a fatal heart attack, the summer after that particular Christmas. And—joy of joys—there is a constant stream of ‘Listen to this!’ YouTube videos, posted by friends, with fresh and delightful holiday-themed picks.

Do I have favorites? Cuts that went on many tapes and CDs? Yes. And what makes them good has to do with the synchronicity of tune, lyrics and presentation. Some artists I like just plow through standards and lay on the cheesy sentiment (IMHO, Willie Nelson’s Pretty Paper is atrocious). Others know how to make a tune that everybody knows completely unique.

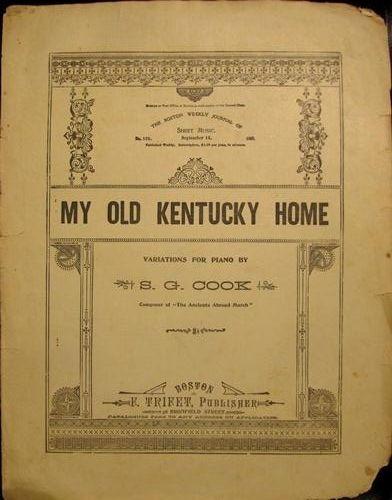

There is a great deal of gorgeous early Christmas music; tunes that have stood the test of centuries, back to when virtually all music was sacred, dedicated to God. It’s not unusual to hear Quem Pastores Laudaveres in the produce section of your supermarket, come November. And there are a handful of songs that justifiably entered the Christmas canon late—Jackson Browne’s Rebel Jesus or Vienna Teng’s Atheist Christmas Carol, grace coming out of the void—but can be welcomed as the world celebrates the coming of the light, whatever your own personal light represents.

It would be impossible for me to choose 10 or 100 Top Christmas Songs, or even top artists. But here are a few I’ve listened to, today, off the top of my head.

Silent Night—the Hollywood Trombones

Joy to the World—the Empire Brass

Sussex Mummers Carol—Burning River Brass

I have a favorite ‘O Holy Night’ (Jewel) and a favorite ‘Sleigh Ride’ (Sam Bush) and a favorite ‘We Three Kings’ (the Roches) and a favorite ‘White Christmas’ (the Mavericks). I have favorite albums (‘Christmas at Beaumont Tower’) and arrangements. None of these, by the way, comes from Mannheim Steamroller, which tends to give me a headache. Your mileage, of course, may vary.

Hark! Are the herald angels singing?