At a moment when half of our elected officials are resisting Political Science as means of preserving democracy, or Climate Science as a resource for, say, saving the planet, it must be reassuring to some that the Education field, at least, seems to be pursuing Science these days. Aggressively.

Science standards this and scientific method that and exponential STEM everywhere. Because jobs.

Except—that’s not really the case. Currently, the top ten job opportunities in STEM fields are all in the T part of STEM, and there’s actually not much call for biochemists (and not a lot of money to be made, either). In fact, there are 10 times as many graduates in the life sciences as there are jobs. You can teach, of course, but—the party line is that a STEM degree will take you away from pedestrian careers like teaching into the glamorous world of lab coats and bubbling test tubes.

And speaking of…the ‘science of reading’ has bubbled up, again. If you’ve been paying attention, you’ll know that mainstream media is now eagerly printing pieces claiming that we have known all along, for decades, how to teach reading—that it’s ‘settled science.’ For some reason, these articles claim, benighted teachers everywhere have either not adopted this one sure-fire method, or more likely, their university training did not include scientific reading pedagogy.

Those teachers! Those colleges! When will they accept Science and teach all children to read the same way?

More than enough digital ink has been squandered on the Reading Wars (and accompanying smackdowns of the hard-won expertise of veteran early childhood teachers with actual students)—but this focus on Science is a new twist. No more book whisperers, personal literacy journeys or other soft terms of art. Bring on the scientific worksheets!

Insistent nudging of reading teachers toward Science pales in comparison to Ulrich Boser’s recent headline in the Education Post: It’s Time to Help Teachers Discover the Science Behind How Kids Learn. Boser, according to his bio, is a Senior Fellow, a Founder, a Founding Director, an author and Not a Teacher.

I seldom read anything on Education Post but was drawn to the title, and Boser’s opening statement: We recently surveyed around 200 K-12 educators from across the U.S. to discover their beliefs about learning. The results were not good—and say a lot about the nation’s system of training educators.

Whoa. The nation’s teachers and those who train them, cut down in one sweep, by Science.

Now, I’m no scientist but it seems like the thoughts of 200 (out of nearly 4 million) teachers, captured by a survey, might not be the most valid and reliable evidence, but hey– I learned to read via the look-say method, so what do I know?

I went to Ed School in the 1970s, and back then, we all took classes on learning theory and educational psychology—the science behind how kids learn. I don’t remember a great deal—they were always textbook/lecture/test courses (there’s some irony in that).

But I remember covering Plato, Bruner, Vygotsky, Piaget, all the biggies. We learned about Skinner and behaviorism—operant conditioning was all the rage in the 1970s classroom—but that never worked as it was supposed to in my classroom.

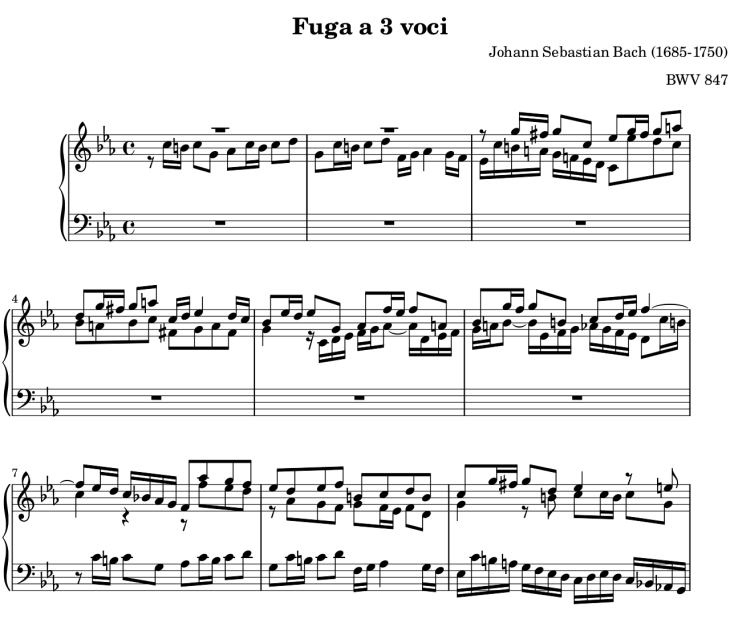

I would venture to guess that most experienced teachers remember fragments of learning theory, adapted and applied to what has actually happened in their daily practice. They know, for example, that there is a sweet spot in learning—what Vygotsky called the zone of proximal development—where new learning is both achievable and challenging. I personally know that prior learning—the gestalt–matters a great deal. I learned this when I began teaching beginning band to kids who’d never had elementary music and couldn’t match pitches or keep a steady beat.

Boser makes a lot of claims, beginning with the ever-popular ‘Teachers (97% of them, he says) believe in learning styles but they don’t exist! So there!’ You have to ask yourself this question: If it is true that 97% of teachers believe there is some prima facie validity to learning styles, based on their lying eyes, what exactly are they missing?

He provides lots of statistics-based examples of teachers’ intellectual failures and misunderstandings, then Boser hits us with this: The overall picture suggests that teachers have weak overall knowledge about learning principles. Out of 17 questions related to learning myths and research-supported teaching strategies, respondents performed only slightly better than chance. Respondents got 8.34 questions correct on average—random guessing would give an average response rate of 6.63.

Boser doesn’t have to spell it out any more plainly. Teachers be dumb.

Having set up a giant straw man of an entire professions’ scientific ignorance, Ulrich Boser tells us what we can do about this dire situation. You guessed it—we can get teachers some professional help. Or, as Boser memorably says: How can we create a learning engineering agenda?

Just so happens that he’s the Founding Director of The Learning Agency (‘Part consultancy, part service provider, part communications firm, the Learning Agency’s difference is the science of expertise’). Also: he did a TED talk.

What about the professional development that teachers routinely get, provided by their schools? Isn’t that supposed to be research-based? Teachers in Boser’s survey claimed they got their updated knowledge about teaching from workshops, conferences, school-mandated professional development and colleagues, which sounds about right to me.

Boser, however, feels that ‘leading teacher training materials’ featured an ‘astounding lack of science’ and working collaboratively with colleagues merely leads to ‘anecdotal’ sharing, not (yup) ‘hard science.’

I once worked with a second-career teacher who had been a chemist in a large, multinational corporation for 25 years, but wanted to get out of the rat race and be a teacher (his words) at the end of his work life. He did a year-long, night-courses teacher certification program at a four-year university, and a semester of student teaching, for the tradeoff of more satisfying work at a lower salary. He wanted to ‘give back.’

He had no trouble getting a job teaching Chemistry in a suburban school. The principal was thrilled to get a real, live chemist with applied scientific expertise. I was his e-mentor.

When he arrived at school in August, he was shocked to find that he’d been assigned four hours of Chemistry and one hour of AP Chemistry. They were two different courses! Twice as much preparation—and by the way, school was starting, and nobody had given him any lesson plans. I told him to be prepared to create his own lesson plans. Another shock.

We’d never do anything like this at Big Multinational, he said. Why would every teacher create new lesson plans? That wasn’t efficient.

Because, I said, you haven’t met your students yet. You don’t know what they know or what they need now. You’ll be tailoring and tinkering with your plans all year long—and ask the other Chemistry teacher for advice before you start writing.

Would all teachers benefit from a more scientific approach to teaching and learning? Or should they just go on collaborating, sharing ideas with colleagues and field-testing their own methods and strategies, building a practice around their own observations?

Ask a teacher.