From one of my must-reads, Culture Study, on November 12:

‘If you’re not on TikTok, you might not have heard about the woman who’s been calling religious organizations to see how they respond to a mom’s request to source formula for her two-month-old daughter, whose cries you can hear in the background. (Nikalie does not have a two-month-old daughter; she plays a recording of a baby’s cries in the background).

Nikalie records the conversations (Kentucky, where she lives, is a one-party consent state, so this is legal) and then posts them to TikTok, along with a tally of how many organizations have offered to help and how many have declined. You can see all the videos here, but viewers have been compelled by the overall stats: only a quarter of the religious organizations she’s called have offered direct assistance. The larger the organization, the less likely it is to help.‘

Even if you’ve seen the Tiktok, I recommend reading the Culture Study piece, wherein Anne Helen Petersen deftly dissects this kind-of experiment, pointing out that some of the organizations that did not offer formula or money sent the caller to another resource, where they did.

She also raises the right questions: How do we help the needy efficiently, elevating proven logistics above feel-good impulses? Should religious institutions have serving the poor as an ongoing mission? (Yes.) And—why are there so many needy folks right now?

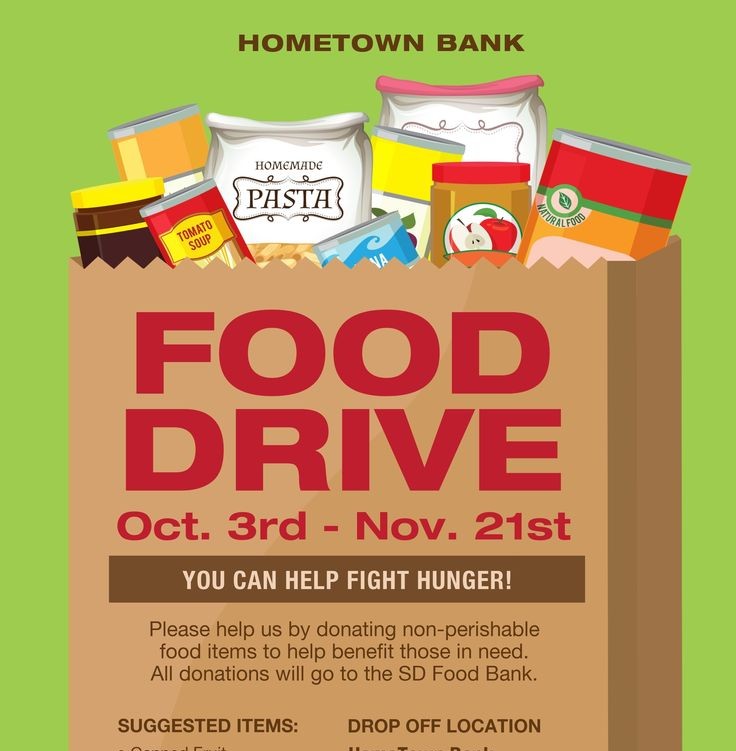

As a veteran teacher, in a relatively well-off suburban school system, I’ve been part of any number of school-based community service projects. My middle school used to have a canned goods drive around Thanksgiving.

Homerooms competed to see who could bring in the most cans, with the winning class getting donuts and cocoa. Piling the cans into an edifice—you can make a fairly impressive structure with hundreds of them—then plunking a few students in front of the Great Can Pyramid—well, there’s a shot for the monthly newsletter.

But it always bothered me. There were the rabid competitors—Come on! Just go where your mom stores cans and put a few in your gym bag!—who were definitely in it to win it. I mean, free donuts! From the bakery! There were also plenty of well brought-up girls who wanted to feed the poor (and maybe get their photo in the newsletter), counting and re-counting the cans.

The people who didn’t get mentioned: The Student Council advisor who had to transport a thousand-plus cans to the food bank. And food bank volunteers who had to organize the donations, throwing out outcoded or bulging cans of beets and butterbeans.

Not to mention the folks who depend on food banks, getting there early to get what they actually needed (formula, perhaps) and not be left with stuff that had been sitting in suburban cupboards for years, unused.

For several years, I was advisor to the National Junior Honor Society, the stated mission of which was acknowledging scholastic excellence in middle schoolers. Hey, I was always down to honor academic effort, and lots of my band kids were in the NJHS. It was one of those “make of it what you will” volunteer jobs, and I thought it was a place where some smart kids could wrestle with the idea that they were more fortunate than—well, the rest of the world. A middle school kind of noblesse oblige.

One year, we raised money by hosting a dance, then sent those proceeds to a homeless coalition in Detroit. It was a pretty bloodless project—the only outcome for us was a nice thank-you note from the nonprofit—but it was a good opportunity to talk about just who the homeless were, and how you get to be without shelter in the richest country in the world.

Another year, we “adopted” a family through the local Salvation Army (this was before their stance on LGBTQ folks was questioned), to provide a nicer Christmas. The first order of business, after raising a few hundred dollars, was discussing the word “adoption,” relative to extending charity to folks who are less well-off, but live in the same community. We were not adopting anyone; we were providing temporary, anonymous assistance.

Then, we went shopping. There were two cars full of 8th graders, with lists provided by the Salvation Army, pushing carts around Meijers, picking up a holiday dinner and gifts for everyone in our assigned family. What was interesting to me was the assumption that “the poor” weren’t like the kids in the NJHS; they should have to live with less expensive, less attractive products and even be grateful for them.

In our assigned family was a girl (14), who needed a warm winter jacket. The kids debated: the cheaper, ugly one or the acceptable style that was $20 more? This took a lot of time, standing in the aisle. I asked: Would YOU wear cheaper/ugly? No. Never in a million years. So—why should she? The answer (a good answer): because then we could get frozen macaroni and cheese for their Christmas dinner.

In the end, the chaperone mom and I kicked in extra cash, and we got them both. But life isn’t always like that.

I don’t think you can teach kids to care for their neighbors via school projects—but you can teach them to think about inequity and compassion. Just because SNAP benefits returned this month does not mean the less fortunate will be well fed in the long term. And the misfortunes of rising unemployment, rising food prices and rising social uncertainty will not be ending soon.

The foundations for eliminating food insecurity are cracking. The best gifts: Money and time. Happy Thanksgiving.