In my long and checkered career as a classroom teacher, I taught instrumental and vocal music, mathematics, ESL and the occasional oddball middle school class necessitated by the fact that, as a (qualified) music teacher, my music classes could contractually be huge—so I could be assigned a class of kids left over in the scheduling process by putting 75 students in one beginning band class.

I learned a great deal while teaching things I wasn’t technically qualified to teach. But I never got to teach my favorite non-music subject: Social Studies. (Notice that I didn’t call this subject History or Economics, two narrowly defined class titles that are approved by the anti-public school mafia.)

I think that poor, maligned Social Studies, the last outpost of mostly-untested subjects, is probably the most critical academic field for K-12 students to explore, if we want them to become good neighbors and engaged citizens. It’s where they learn (theoretically), what it means to be an American.

But ask any third grade teacher what gets short shrift in their daily lessons. Or ask which secondary curricula is the most scrutinized by people who haven’t been in a classroom in decades.

When you hear people talk about how we need more Civics education in this nation, what they want is a range of social knowledge: history, of course, but also government, geography, sociology, political science and early-elementary trips to the fire house and the public library.

What it means to be an American. How we got to where we are—arguably, the most powerful nation on earth. What values we claim to embrace. How physical and historical features, and population migrations, shaped our culture.

Isn’t that critical, essential stuff? Not to mention engaging—when taught with the mindset that this is the content that one needs to know, to become a fully functional adult in the United States?

Today, which used to be the day we honored Christopher Columbus for a bunch of shady reasons, might be a good time to ask some questions about social studies, and their current place in the school curriculum.

- Why are state Social Studies standards so contentious? Why are these standards important? Cui bono?

- Speaking of contentious, why are we observing Indigenous Peoples Day today, and not Columbus Day?

- What role does truth have in studying our world?

- What does it mean to belong to/ be active in a political party? How does this vary in other nations?

- What happens when elections divide neighborhoods?

- What does excellent teaching look like, in the broader field of social studies?

- How do we deal with world-changing events when they’re happening in front of our students? Are schools embracing catastrophism, as Rick Hess suggests here: Catastrophism has exacerbated tribalism, distorted journalism, and squeezed out measured discussion of public policy. It’s also spilled over into schools and colleges, where tried-and-true virtues like civility get dismissed as inadequate in the face of imminent catastrophe.

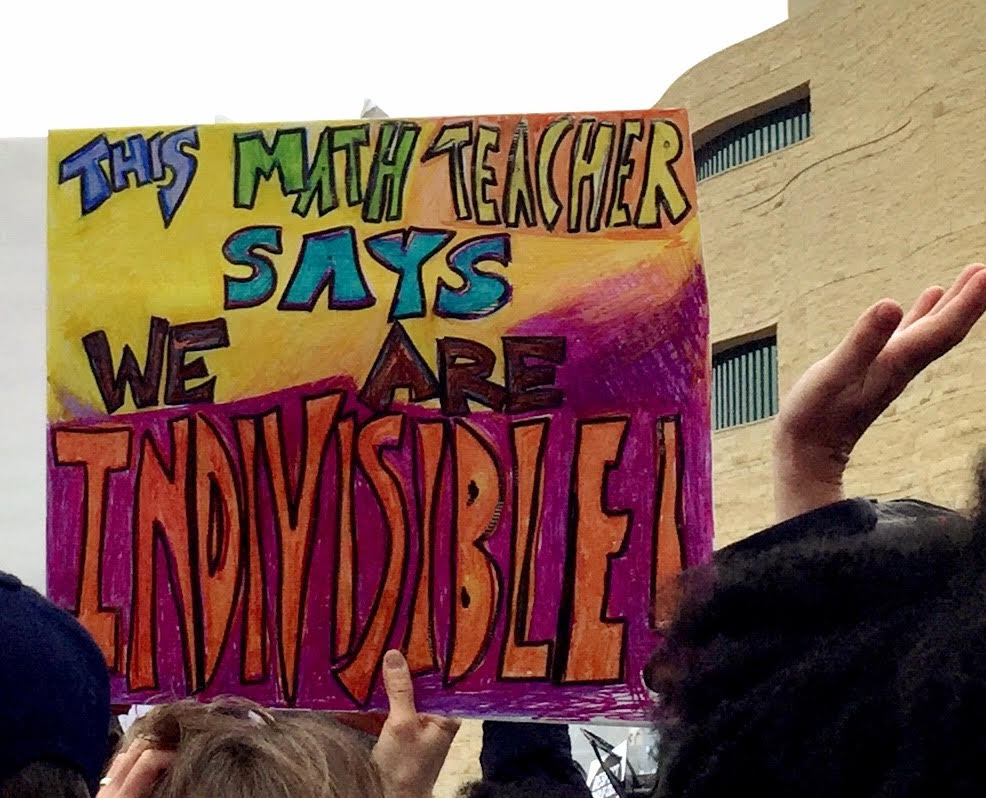

My fear is that Social Studies, an incredibly rich and applicable field of interrelated content, will be further squeezed out of the curriculum, or become a dry, testable, bunch-of-facts sequence, none of which bears relevance to the diverse, often catastrophic world our students live in. What Hess calls catastrophism might just describe how passion has always shaped our politics.

And politics, civil or not, is just the means to get the world we want.

A couple of years ago, the Michigan Democrats posted a statement on their Facebook page:

The purpose of public education in a public school is not to teach students what parents want them to be taught. It is to teach them what society needs them to know. The client of the public school is not the parent, but the entire community, the public.”

The statement was quickly criticized—Parents’ Rights!—and walked back, but I think there’s some truth there. Parents want their children to be literate, and numerate, for sure. But when it comes to understanding what science tells us about climate change, or encouraging 18-year olds to become informed voters, should a subset of parents be able to shut that whole thing down?

Here’s a toast to social studies teachers everywhere, as we approach November 5. You go.