I am a big fan of Jess Piper, a veteran teacher from Missouri, who left the classroom to run for office, and has since reshaped the conversation around why red-staters vote against their own interests. Piper writes often about a childhood spent bouncing around the south, and the family values that influenced her.

When people (including myself here) shake their heads and wonder how so many citizens–despite glaring, flagrant evidence to the contrary–can still stubbornly believe that Trump is leading the country on the right track, it’s helpful to read Piper’s blog. She gets it.

Mostly, I read Piper for her insights on working-class voters–because my own father, were he still alive, would (despite many years of voting for Democrats, post-War) probably be a Trump supporter, voting against his own interests.

Not a careless, “protect my wealth” country-club Republican. But a grievance-driven voter who resented those he believed were simply and unfairly handed benefits and perks, things he would never enjoy, no matter how hard he worked.

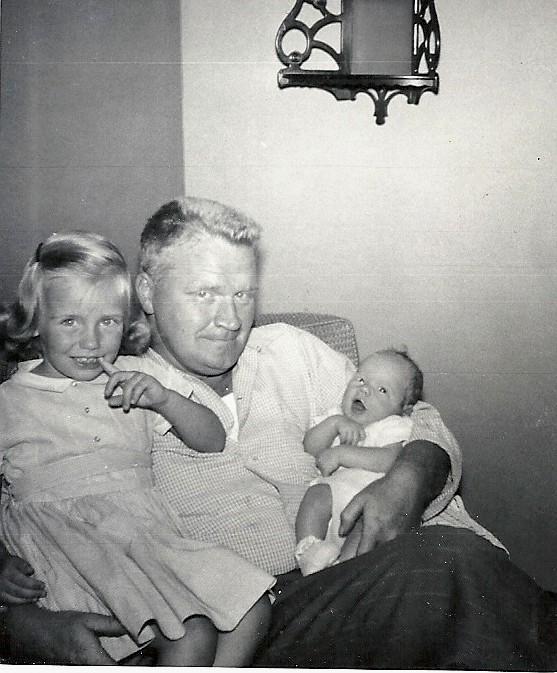

Fear and resentment—and the overwhelming conviction that the little guy never gets ahead—were deeply embedded in his character. That doesn’t mean he was not a good father; he absolutely was, caring for his family and living up to his responsibilities as a hard-working adult and citizen who never missed an election. He was a proud Teamster, a church-goer, and the man who drove me 90 miles one-way to take flute lessons at the university.

My dad served in World War II, in the Army Air Corps (later the US Air Force) in the Pacific theatre. His plane was shot down, in 1944, over the Sea of Japan, and the crew was rescued by an Australian sub. He lost his 19-year old brother Don in the first wave of Marines taking Iwo Jima in February of 1945. I wrote more about these things here, explaining why my dad really never got over the war. But it was more than his wartime experiences that molded his character.

He often expressed the sense that he’d been cheated—that other, less-deserving people were moving ahead, because they had money, or were currying favor, while he (a realist from the poor side of the tracks) was left behind. He voted for George Wallace in 1968, because Wallace claimed there wasn’t a dime’s worth of difference between the two parties: both were corrupt and run by elites. Sound familiar?

Thom Hartmann’s new piece– Culture Is Where Democracy Lives or Dies, Because Politics Always Follows the Story a Nation Tells Itself—goes some way to explaining what’s happening today, but also why my dad, surrounded by protests against the Vietnam war and girls burning their bras, turned to a man who supported segregation and repudiated progressivism: ’ Like no candidate before, Wallace harvested the anger of white Americans who resented the progressive changes of the 1960s. Wallace supporters feared the urban violence they saw exploding on television. With tough talk and a rough-hewn manner, Wallace inspired millions of conservative Democrats to break from their party.’

Like many of Trump’s supporters today, my dad saw Wallace as a truth-teller, an advocate for the working man, someone who would work to defend cultural norms around race, gender, authority and social policy. Even when those norms were outmoded, unjust or morally repugnant.

Today, I know better than trying to talk an irrational, ruby-red voter out of their convictions. I really do understand how pointless, even damaging, it is to accuse Trump voters of destroying democracy and erasing progress. Because I spent, literally, years of my life trying to (cough) enlighten my father, who treated me like other fathers of the era treated their know-it-all college-student kids: as spoiled brats who needed to let the real world take a whack at them.

My father died in 1980, of a brain tumor, at the untimely age of 58. I never changed him, but he never changed me. He thought a college education was a waste of time and money, although when I graduated, he came to commencement exercises and danced with me at the Holiday Inn afterward.

Later, it dawned on me: the fact that he and my mother couldn’t contribute financially to my college education, and couldn’t help me navigate enrollment, might have been part of his insistence that college was for the privileged, not families like ours.

All of this happened in a time when news and opinion came from three mainstream TV channels and the Muskegon Chronicle. Who do Trump voters turn to now for news? Is that source supporting their racism, sexism, xenophobia and bitterness? Is it filled with fact-free resentment?

Where do we start in changing minds and hearts? I wish I knew.