If you’ve been paying attention to the DOGE Brothers—Elon-n-Vivek—lately, as they explain their personal theories around the failures of American parents to instill tenacity and a work ethic in our young citizens, you may have seen Ramaswamy’s rant on our deficit culture: A culture that venerates Cory from “Boy Meets World” or Zach & Slater over Screech in “Saved by the Bell” … will not produce the best engineers. More movies like “Whiplash,” fewer reruns of “Friends.”

Ramaswamy goes on at some length, all Tiger Dad, about the virtues of immigrant parenting vs. native-born slacker parenting. As a veteran teacher, and thus long-time observer of American parenting, I think he’s flat-out wrong. True, there are parents who simply want to make things easy for their kids. But there are also plenty of non-immigrant parents who run a tight ship, academically, pushing their kids toward competitive excellence, breathing down their necks. The idea of hard work leading to a better life is not exclusive to immigrants.

It’s tempting to ignore the DOGE boys’ blah-blah on Twitter, although our incoming President has anointed them fixers of the entire political economy. It’s hard to see how your average Trump voter will suddenly decide that it’s time to claw their way to STEM careers via choosing the right TV characters to admire, or deciding not to (Vivek’s words) venerate mediocrity any more.

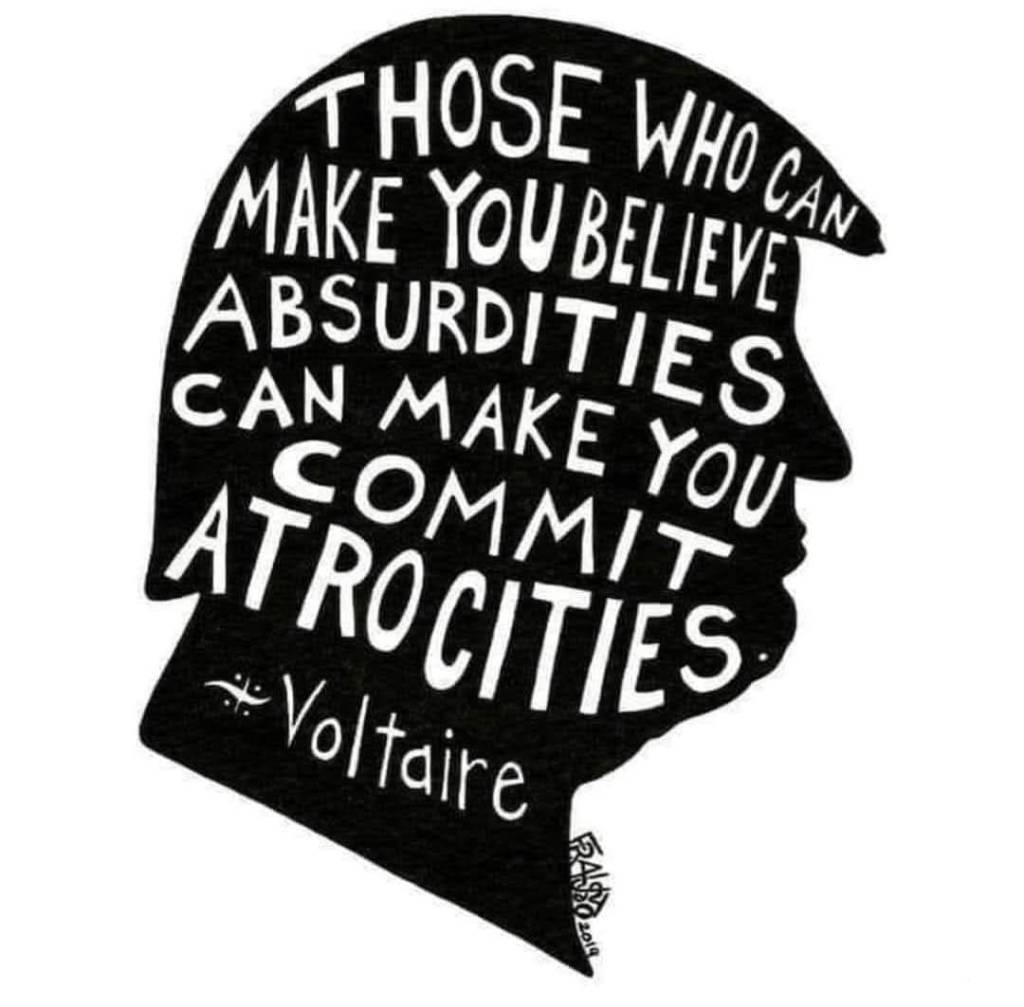

But we’re not going to nurture talent and work toward genuine accomplishment via movies like Whiplash, which is possibly the worst movie about education ever produced.

OK, maybe not the worst movie ever. But a stylish, seductive acting tour de force based on All the Wrong Stuff. An excellent showcase for two major talents–J.K. Simmons and Miles Teller–but with precisely the wrong message, for young people who want to excel in spite of setbacks, for educators, and for anyone who ever hoped making music was a rewarding, life-affirming pleasure instead of just another competition.

Several years ago, I had a very talented drummer–call him “Zach”– in one of my middle school bands. Zach was a natural–great innate rhythmic sense, great unforced stick technique and most important, a kind of fearlessness you don’t often see in an 8th grade percussionist. When something went wrong in the music-reading process he–perfectly illustrating the cliché– never missed a beat. Zach was what teachers call a “good kid,” to boot–polite, friendly, and willing to let other kids have the spotlight often, even though he knew he was a better drummer.

Zach’s mother was a physician, and at our first parent-teacher conference, she let me know that my ace drummer’s biological father (someone he now saw only sporadically, once or twice a year) was also a musician. She was clear: her son’s formal musical education would be ending with 8th grade; it was “too risky” to have Zach get involved in the high school band program, even though he was interested in doing so.

Zach was bound for better things than music, she said, adding a few bits of folk wisdom about how musicians aren’t trustworthy, goal-oriented or even rational, and make terrible husbands and fathers. It was her story, and she was sticking to it.

When I saw Whiplash I remembered that conversation with Zach’s mother. Because Whiplash is pretty much a dishonest conflation of myths (the only way to pursue excellence is through cut-throat competition) and truths (a lot of music teachers embrace that myth, the blood-and-thunder school of music teaching). The artist as anti-social and single-minded, driven stereotype.

When I watched J.K. Simmons, playing Fletcher, the tyrannical jazz band director, scream “MY tempo! MY tempo!” I flashed back to all the petty dictators I’ve seen on the conductor’s box, over 50 years of being a professional musician and school music teacher. I’ve witnessed at least a dozen school band directors say the exact same thing, transforming into little Napoleans, using their baton as weapon, “proving” that students must be prodded into worshipful obedience in order to play well.

Here’s the thing: you can be a superb, meticulous, demanding music teacher without being a hostile jerk. You can also be a driven, determined, even obsessed music student, bent on creative brilliance and perfection, without being inhuman or ruthless.

In a movie supposedly about “what it takes” to achieve true excellence in performance, we never saw Fletcher teach, or drummer Miles Teller’s ambitious character, Nieman, learn anything about music via guidance, example or instruction. Everything that was accomplished happened via psychological manipulation: Terror. Lies. Tricks. Bodily abuse. Even, God help us, suicide.

It was a movie designed to prove Zach’s mother right: music is a rough, vicious game, filled with people whose talent means more to them than family or human relationships. It’s about ego–and winning.

Except–it isn’t, really. Music is available to everyone, from the supremely talented to the amiable, out-of-tune amateur. It’s what we were meant to do as human beings–sing and play and express our own ideas.

Let’s not turn anyone away, Mr. Ramaswamy.