So—when we’re immersed in the pre-election floodwaters of political revenge speech, it’s easy to snicker at the misfortune, if that’s the word, of right-wing social media edu-star Corey DeAngelis.

DeAngelis is—was?—the real deal, in education policy world. Not the kind of education policy that would re-build or energize our public schools, of course, but an attractive and even charismatic mouthpiece for the anti-union/school choice/privatization movement.

If you’re unclear on what happened to DeAngelis, last week—here’s the story. (And here’s an interesting, even kind, response, from another one-time school choice advocate.)

If this were, say, 2014, when Corey DeAngelis was pursuing a skeezy “alternative career” that eventually became public knowledge, lots of folks would see it as an inside-baseball kind of chuckle—conservative education spokesperson gets caught being himself, ho-hum.

But the nature of public discussion about our schools has changed.

There have always been—going back to Thorndike vs. Dewey—vigorous arguments about the right way to do public education. Most people (including people who work in actual schools) don’t pay attention to these theories, philosophies and policies, unless they’re directly impacted. They focus on other aspects of schooling. And parents, by and large, are happy with the public schools their kids attend.

One of the things Corey DeAngelis contributed and honed, in these verbal ed skirmishes, was nastiness. The kind of unsubstantiated nastiness that we’re now hearing every day from political candidates on the right. Words like lazy, dumb, failing, greedy, groomers, socialists—and, of course, unions as root cause of all that is wrong with America and her children.

DeAngelis is one of the leading spokespersons, on social media, in the wave of anti-public education discourse we’ve experienced in the past eight years or so. I wrote about some of the things he’s said, in respected publications, last May.

I posted a tweet about that blog post, asking WHY DeAngelis and others are trashing public education? What’s in it for them? Because this onslaught of anti-public education blather is not doing the nation and its children (no matter where they go to school) any good. This WHY was a serious question, BTW.

I got lots of tweeted responses, from DeAngelis’s army of followers, to whom I would ask the same question: What, actually, are you fighting for, when it comes to education? Here are a few of those tweets:

Union Mouth! (followed by a string of vomit emojis)

I took my kids out of the gladiator academy/commie indoctrination center. Best choice I ever made.

Staffed by mediocrities (sic) who act like martyrs

Corey is bringing the future of education. Say goodbye to your current paradigm of croneyism and union interference.

The govt “school” system is nothing more than a taxpayer pipeline to labor union coffers, used to then (re-)elect politicians who promise more money for the pipeline. Education was never the point.

Public schools are a Dredge (sic) on society. Teachers are even worse.

And—my personal favorite:

Retire, you old hag.

I found myself blocking responses from people with names like—and I’m not making this up—Sexy Fart Bubble. Also wondering how school policy went from being a question of qualified staff and resource allocation to taking ugly potshots at teachers, school leaders and the millions of families who rely on public education.

I know better than to sputter about—or worse, respond—to random on-line vitriol. It’s acceptable now, evidently, to lie on public platforms; calling attention to falsehoods (or snickering at a messenger’s personal problems) is a distraction from focusing on what matters in debates about our schools.

Because—contrary to what Corey DeAngelis’s followers expressed, education has always been precisely the point. For better and worse, for everyone involved. Education has never been settled science. Our children are exposed to different influences and technologies than the previous generation of students; likewise, educational practice has to evolve.

Serving children’s educational needs adequately will—must—shift over time. And change is hard. Working through the changes, especially after a global disruption, demands civil discourse. Professional judgment. And an appreciation for facts.

So—no schadenfreude over seeing someone, whose minions called me “Union Mouth,” be exposed and having his name quickly erased from an array of education non-profit websites. There are far bigger fish to fry at the moment.

When one of your options for Leader of the Free World is seriously threatening to deport 30 million people, a large percentage of whom are children, it seems wrong to fuss over books somebody’s mom doesn’t like. Or spend a lot of time and effort trying to persuade people that teachers’ organizations, with their focus on working conditions in our schools, are harming children.

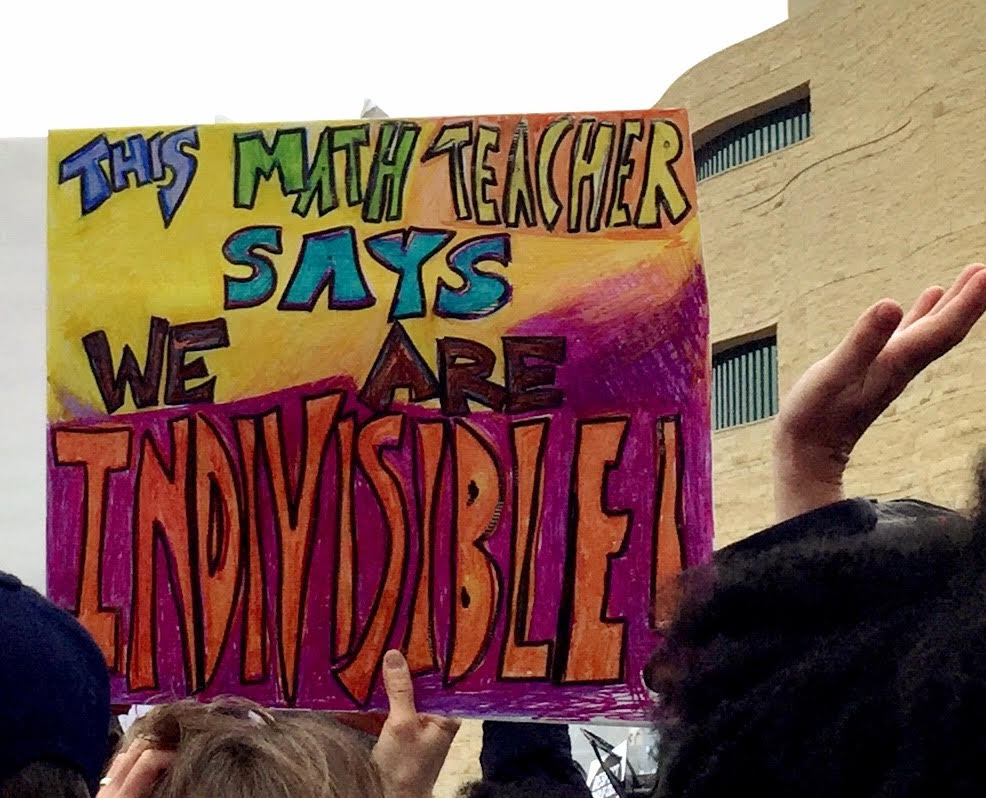

With all the free-floating fear and loathing in the American zeitgeist right now, it’s harder than ever to establish a classroom where students can develop the confidence to be a community. I am 100% on the side of educators who declare that students can’t learn unless they feel safe. The corollary to that is that teachers can’t learn and grow unless they feel safe, as well.

We are living in unsafe times.

If you want to influence policy change in public education, bring your best ideas and an open mind. Leave the nastiness behind.