Truth nugget: Education policy is 100% shaped and impacted by the fact that three-quarters of the education workforce is female.

Another truth nugget: After Trump was elected in 2016, over a million women descended on Washington DC to march against what he stood for.

And now, after the events of Summer 2024? Well, do your own math, draw your own conclusions. Maybe start your own organization and host a national call.

As the inimitable Dahlia Lithwick noted: The court granted itself the imperial authority to confer upon the president powers of a king, but although Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson said as much in their respective dissents, it fell to Big Daddy Chief Justice Roberts to intone to his readers that their aggregated dissents strike “a tone of chilling doom that is wholly disproportionate to what the Court actually does today.” Implying that the dissenters were overreacting, and without ever attempting to address the substance of their claims, Roberts accused them of “fear mongering on the basis of extreme hypotheticals about a future where the President ‘feels empowered to violate federal criminal law.’”

In other words, sit down ladies. You’re hysterical. We don’t appreciate your chilling doom or your extreme hypotheticals. A President who feels empowered to violate federal law? Hahaha! That could never happen!

This type of response could come in handy for pacifying those whose policy/practice wheelhouse is education. It’s a familiar tone policing strategy for those of us whose professional lives revolve around the classroom, especially in public schools. You’re overreacting! It’s only bus duty! What’s one more kid in your class? Why can’t you maintain control over 24 second graders on Zoom?

But. What if women were united to push the ed policy envelope? Connie Schultz, wife of the SENIOR Senator from Ohio, Sherrod Brown, has some wise words about what happens when women organize: I know that something else—something glorious—often happens when women gather for a cause. I think of it as coming home.

More wise words, these from Kate Manne:

Many of you are now in the same position I am in: all in for Harris as the person who can beat Trump and head off the incalculable threat facing our country. We are terrified as/for girls, women, and any person who can get pregnant. We are terrified as/for the racially marginalized people who Trump has firmly in his sightlines. We are terrified for trans and queer folks who would face existential threats to their well-being and very existence under the next Trump administration. We are terrified for whatever semblance of democracy that remains and might perhaps be rebuilt. The list goes on. There is no question that Harris’s candidacy will open up a torrent of misogynoir, the intersection of misogyny and racism (particularly anti-Black racism, although Harris is also of course South Asian). It’s our job to fight it in our circles and even ourselves.

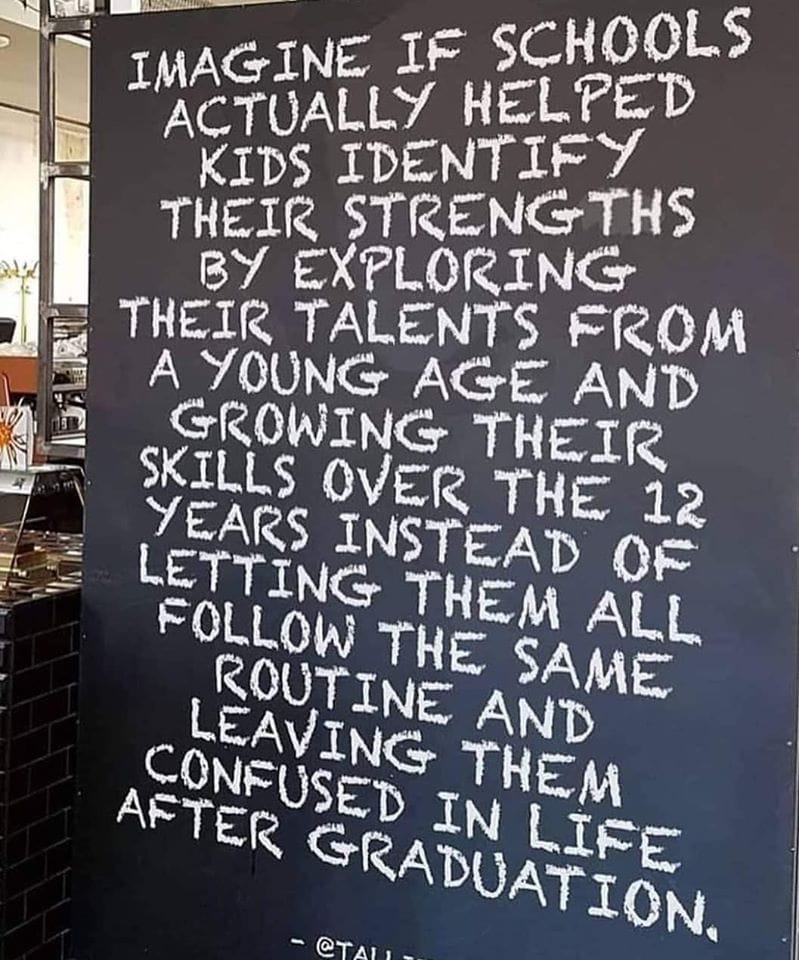

Do women have the power to transform thinking about the bedrock value of a strong public education system, in the face of Project 2025? Just a reminder:

Trump tells voters on his campaign site a few ways he would manage education:

- Cut federal funding for schools that are “pushing critical race theory or gender ideology on our children” and open civil rights investigations into them for race-based discrimination.

- End access for trans youth to sports.

- Create a body that will certify teachers who “embrace patriotic values”.

- Reward districts that get rid of teacher tenure.

- Adopt a parents’ bill of rights.

- Implement direct elections of school principals by parents.

That last suggestion is sheer folly, by the way —any teacher OR school administrator will tell you that it’s a recipe for never-ending chaos and enmity in schools. Besides, parents can run for the local School Board or elect people to that Board who will select appropriate school leaders for the community. I personally have seen, on multiple occasions, a group of parents make things hot for a principal, via a democratic process involving their elected board. I have also seen good administrators protected—by the same Board—from a single outraged, vindictive parent.

Kate Manne is right when she says we need to fight bad policy and reprehensible candidates “in our circles” and even in our selves. And nobody is going to fight against misogyny and racism more effectively than the people who are impacted. Therefore, protecting your public school may be most effectively accomplished by women, gathering for a cause.

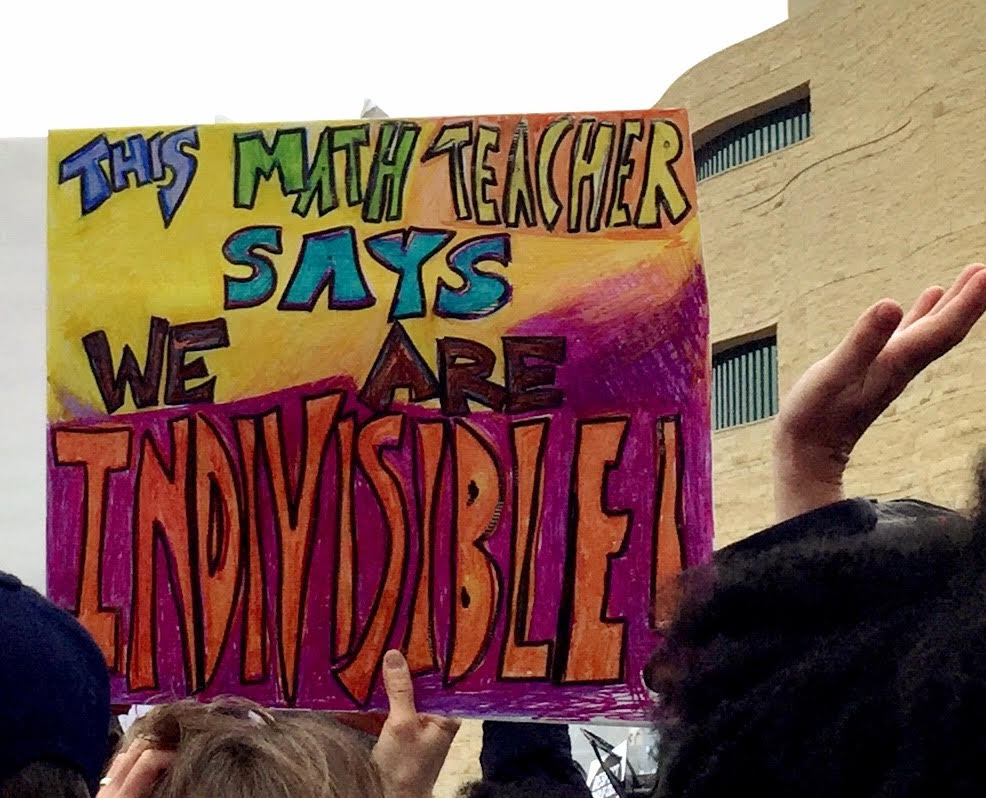

Don’t want public education to be taken down by the slings and arrows of Moms4Liberty and Project 2025? Talk to your friends. Put up a sign. Donate. Volunteer. Organize in Zoom circles. Repeat vigorously for the next 82 days.

Derek Thompson of The Atlantic points out, in a revealing column that …parties aren’t remotely united by gender. After all, millions of women will vote for Trump this year. But the parties are sharply divided by their cultural attitudes toward gender roles and the experience of being a man or woman in America. When the VOTER Survey asked participants how society treats, or ought to treat, men and women, the gender gap exploded. Sixty-one percent of Democrats said women face “a lot” or “a great deal” of discrimination while only 19 percent of Republicans said so. In this case, the gender-attitude gap was more than six times larger than the more commonly discussed gender gap.

With a majority-female workforce, change will come only when women demand policy that invests in public education. Women teachers, often working mothers, value tenure. Women teachers do not want mandated certification of their “patriotic values.” And they don’t want a President or Congress that embraces the horror show of Project 2025, especially when it comes to education.

Reminder: The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court called his female colleagues “fear-mongers, on the basis of extreme hypotheticals.” In writing.