Maureen Dowd, in a NYT article entitled Attention, Men: Books are Sexy!:

Men are reading less. Women make up 80 percent of fiction sales. “Young men have regressed educationally, emotionally and culturally,” David J. Morris wrote in a Times essay titled “The Disappearance of Literary Men Should Worry Everyone.”

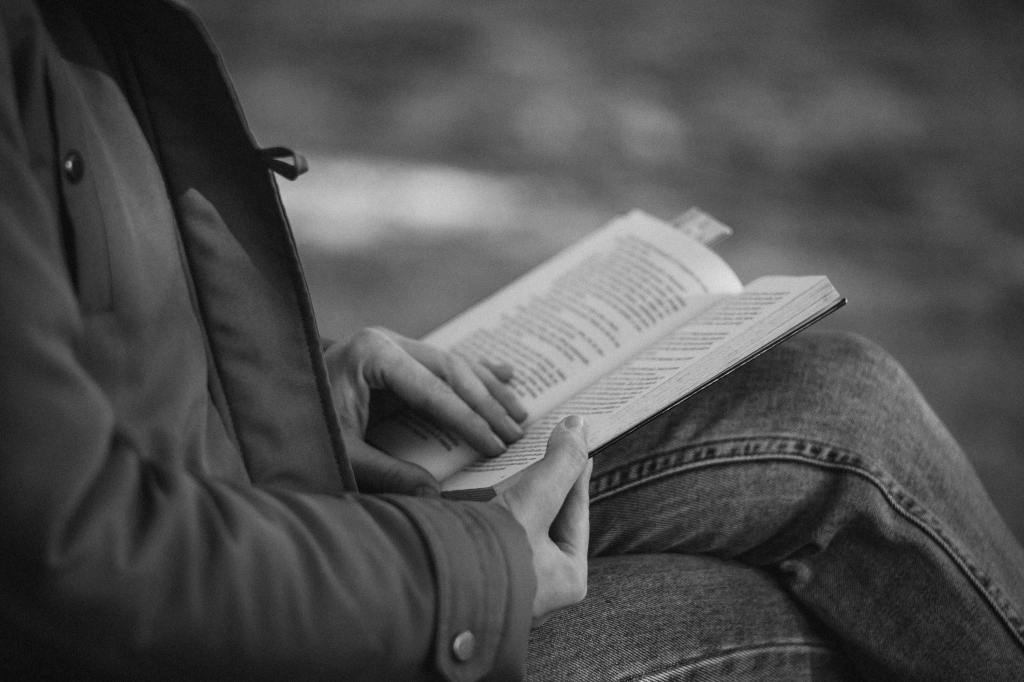

The fiction gap makes me sad. A man staring into a phone is not sexy. But a man with a book has become so rare, such an object of fantasy, that there’s a popular Instagram account called “Hot Dudes Reading.”

It’s enough to make me re-up my abandoned Instagram account.

I also sincerely hope that Maureen and I are not a dying breed, older women (we are the exact same age) who find Men Who Read attractive. I once experienced a tiny swoon when I read that Stephen King carries a paperback with him, wherever he goes. You know, in case he has to wait 10 minutes in line at the post office.

This is more than just my elderly romantic fantasy, however. I think Men Who Read are—or should be—a national education goal. Not men who can decode, nor men who can type fast with their thumbs or pass tests about content. Men who actually enjoy reading.

Reading to use their imagination, rather than seeing prepackaged ideas on video. Reading and—important–evaluating information. Using the language they absorb, via reading, in their daily interactions with others. Reading for pleasure.

Personal story: When I met my husband, he told me about working third shift at the Stroh’s factory in Detroit, while he was in law school. His job involved dealing with a machine that flattened cardboard beer cases and needed tending only at certain times. The rest of the time he filled with reading, hours every night. He would take two books to work, in case he finished the first one. He read hundreds of library books, mostly popular fiction.

He is still that person, 46 years later. Swoon-worthy.

When I read (endlessly) and think about how we’re teaching reading these days, it strikes me that the discussion is almost entirely technical: Do we really have a “reading crisis?” Why? Is it the fault of a program that was once popular and taught millions of kids to read, but is now being replaced, sometimes via legislation crafted by people who haven’t met first graders or stepped foot into their classrooms?

I recently had a conversation with a middle school teacher in Massachusetts who is a fan of phonics-intensive science of reading curricula, largely because she gets a high percentage of non-readers into her Language Arts classes, kids who have big brains but no reading skills. She’s had some success in getting them to read, using sound-it-out instructional materials they should have experienced in early grades.

Good for her. And good for all teachers who are searching (sometimes in secret) for the right strategies to get their particular kids to read. But I’d like to point out that if the technical skills of reading aren’t matched by reasons for reading, it’s like any other thing we learn to do, then abandon. I’m guessing my friend’s students want to learn to read, because they like her, and they find what she’s teaching them interesting.

From an Atlantic piece: ‘The science of reading started as a neutral description of a set of principles, but it has now become a brand name, another off-the-shelf solution to America’s educational problems. The answer to those problems might not be to swap out one commercial curriculum package for another—but that’s what the system is set up to enable.

A teacher must command a class that includes students with dyslexia as well as those who find reading a breeze, and kids whose parents read to them every night alongside children who don’t speak English at home.

There you have it. We’re looking, once again, for a one-size-fits-all solution to a technical, easily measured “problem”—reading scores—when what we really need is honest reasons for people to pick up a book. Or a newspaper. To enjoy a story, or a deep dive into current issues.

My dad, who didn’t graduate from HS and had a physical job all his life, came home from work every afternoon and read the newspaper. He was more literate than many college grads I know.

He had reasons for reading. He was not carrying a smartphone and had only three TV channels, undistinguished by political points of view. He read TIME and LIFE magazines. I disagreed with my father on almost every issue, back in the day, but he could marshal a political argument. Because he was a reader.

So why are reading scores dropping? Curriculum and poor teaching are lazy, one-note answers. If we want a truly literate population, we need to make reading and writing essential, something that kids can’t wait to do. Because it’s a passageway to becoming an adult, to succeeding in life, no matter what their goals are, or how they evolve.

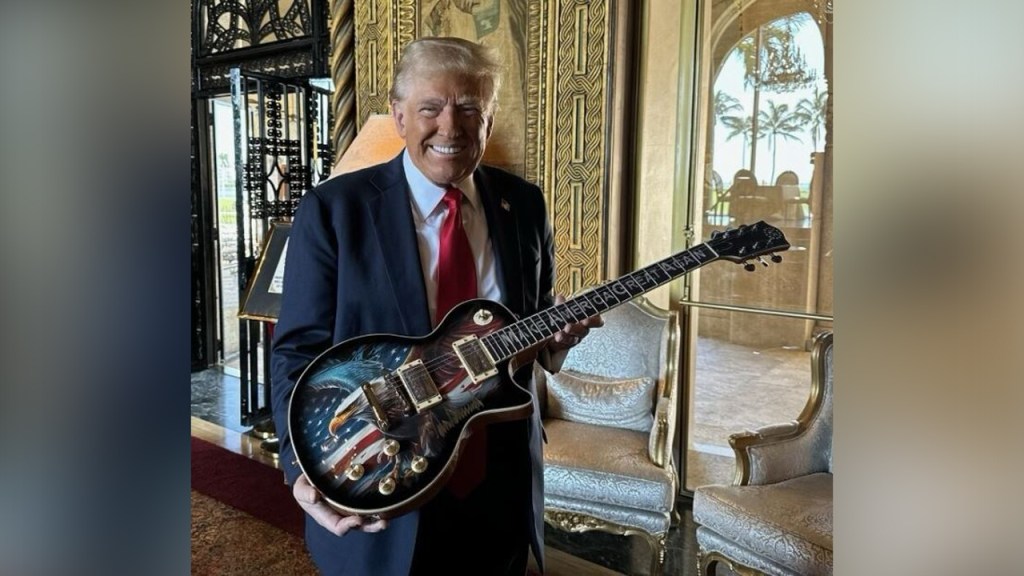

We currently have a president who doesn’t read his daily briefings, and bases his critical viewpoints on hunger in Gaza on what he sees on TV. But we used to have a president who published an annual list of his ten favorite books.

Which one of them is a (sexy) role model?