For most of my adult life (other than a brief but wonderful stint in the People’s Republic of Ann Arbor), I’ve been the proverbial blue dot on a red background. Although I am out there as a Democrat (on the executive board of the county party, and Democratic candidate for office), I always felt fine about living near, and occasionally hanging out with, Republicans.

They were my neighbors and my work colleagues, the white-collar parents of my students, singers in the church choir I directed. When we moved to northern Michigan, it was easy to understand (if not align with) the uber-conservative, agricultural, take-care-of-your-own legacy of the small rural county where I now live. For long stretches of time, I had a Republican state legislator in mid-Michigan who exemplified cross-the-aisle politics for the greater benefit. I thought I understood good people with different political beliefs and habits.

That was then, of course.

I think the distinction today is not Democrats=good / Republicans=bad. It’s not about liberal vs. conservative, either. What we are seeing is an elevation of fear and disinformation, the breaking of the contract of democracy, where majority beliefs, rule of law and consideration of the common good are suppressed–in favor of anger, chaos and feeding the greed of apolitical billionaires and those bent on amassing power.

Anger and resentment. Fear. Disinformation. Crushing respect and generosity of spirit.

There’s a wonderful, brief passage in Elizabeth Strout’s newest novel, “Tell Me Everything.” One of the minor characters volunteers at a food pantry, because she’s lonely and likes feeding people. She meets a nice man on an online dating site, and they begin a relationship. He tells her he knows that many undeserving people go to food banks and take food they don’t need—so she stops volunteering. And that, Strout remarks, is how the divisions in our towns and families begin.

Resentment. Disinformation. Crushing the human urge to share and socialize. Simple stuff—the kind of things kindergarten was designed to ameliorate. The kinds of things that a good education should serve as prophylactic against.

Years ago, when school of choice language became law, and charter schools began popping up in Michigan, it seemed to me that the people who were driving the movement to destabilize public education had two goals: 1) It’s my money and you can’t have it and 2) I don’t want my children to go to school with them (whomever their own personal “them” was).

Well-funded, non-diverse public schools chose not to participate in school of choice, claiming that there were no seats available for students who lived two blocks over the district border lines. Poorer schools welcomed kids from ‘over the border,’ each one of whom came from a public school district that couldn’t afford to lose them and the public money they brought with them.

I never anticipated that those two principles–let’s call them greed and discrimination–would become the driving force in larger social issues, like immigration, affordable housing, elitism and ‘political correctness,’ trade and the national economy. Illiberal, lawless crapola for schools to deal with, as well, like faux book bans and suppression of the truth in ordinary school curricula. If you think those aren’t really happening, or can be prevented in a blue-state school, here’s a heads-up from the “new” federal Department of Education.

So who ARE these people, the ones actively working to disrupt public institutions (including public schools) and reasonable laws? It’s important that we know, because they’re everywhere now—including Europe. If they’re not conservatives, and not precisely Republicans (aside from the craven, rabidly partisan, power-hungry idiots in Congress), who are they? And why did they think Trump would make their lives better?

Every now and then, the New York Times (and please don’t tell me not to read the NYT) interviews citizens about their political views, another opportunity to wonder: Who ARE these people? Where did they get them?

Last week, the NY Times Magazine published a glossy piece, What Trump’s Supporters Want for the Future of America. Here are some excerpts:

I don’t like the way this country’s turned — all this woke stuff. Stuff that the kids shouldn’t be exposed to. I think I was 18 before I knew that there was gay people, you know?

I believe with Jesus at Trump’s side, America will be safe again.

The left has been so gung ho about just taking away rights and trying to demolish what it means to be an American.

You’re going to see so much economic prosperity, the cost of energy going down.

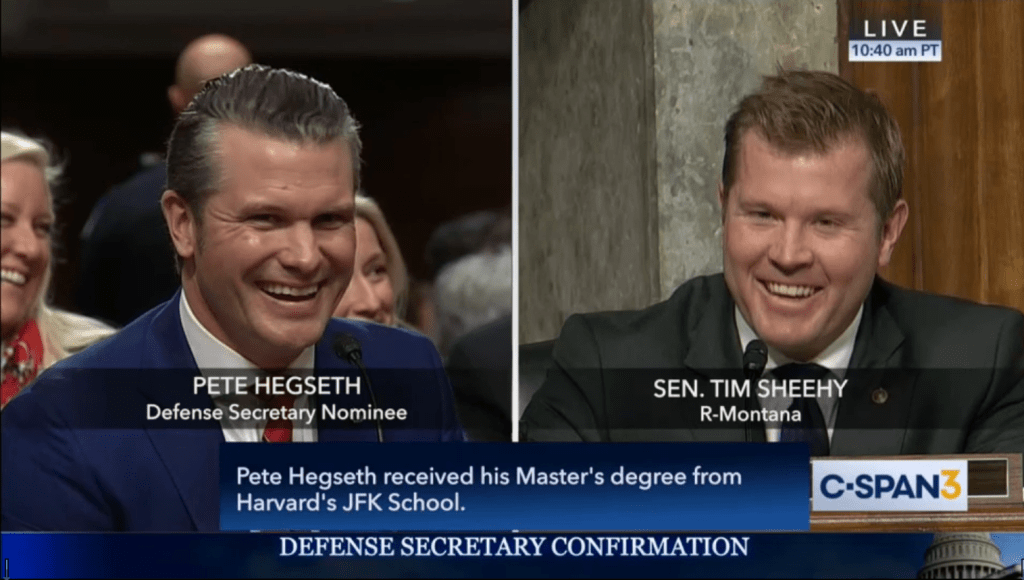

He has excellent people in place in the cabinet as well as throughout the White House staff.

He has become wiser because of what happened to him. He almost died.

What we want is that they give us more hope that immigrants won’t get deported if they haven’t committed a crime.

I was at the Capitol that day [January 6]. It was a setup.

I transferred out of the high school that I was going to graduate from because there were guys that were going into the girls’ bathroom.

We are home-schooling him [son] right now, because of what the schools have become. This one has always been like, obsessed with Donald Trump. I mean, every paper he writes, every project he does in school, everything is about Trump.

All of these people gave their names, occupations and hometowns, and were photographed for the article. They were, apparently, eager to talk about their hopes and dreams for the next four years. None of them were politicians or architects of Project 2025—they were ordinary folks, across the economic spectrum.

It’s easy (and I see this all the time on social media) to call these people dumb—or even evil. But I keep going back to the goals of the 2024 campaigns: Disinformation. Fear. Resentment.

As a lifelong educator, I ask myself if I am partially responsible for young adults who fall for the politicized crapola they hear, who are unable to distinguish just who’s taking away their rights, who believe that the January 6th insurrection was a setup. Why would any student be obsessed with Donald Trump—see him as a hero?

Who are these people? It’s a question that needs answering.