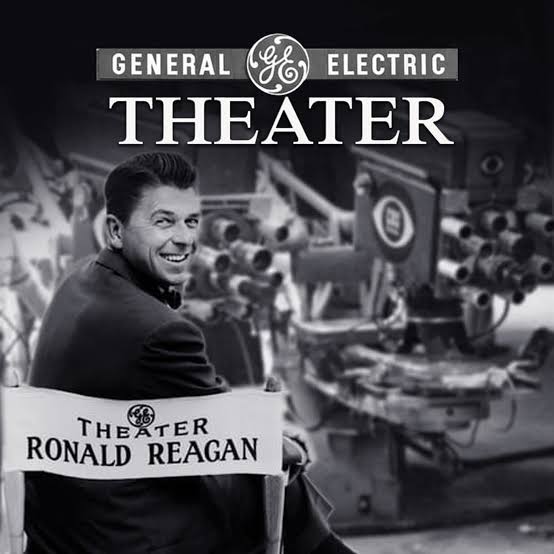

I’m old enough to remember Ronald Reagan hosting General Electric Theater, on Sunday nights, when he would look sincerely into the camera and say “General Electric, where progress is our most important product.”

Presumably, progress was both inevitable and desirable—a mashup of American technologies and innovation, bringing (GE again) good things to life. On television, anyway.

Who would stand in the way of progress? Certainly not schools, who were educating rapidly increasing numbers of Boomer kids, using the modern look-see method of reading instruction, and embracing New Math.

According to family legend, my first grade teacher sent home a note asking my mother to stop letting me read to her, in case she said or did something wrong, impeding my literary progress with pre-approved books about Dick and Jane. She stopped immediately. Teacher knew best.

Stephen Bechloss, on this Indigenous Peoples Day, shared a fine essay on progress:

“Examples of progress are all around us. I carry in my pocket a computer that gives me access to almost all the existing knowledge in the world. That same device allows me to instantaneously connect with family and friends thousands of miles away. I can flip a switch and light my kitchen. If my heart gives out, I can get a new one. I can fly in the sky and travel almost anywhere on the planet. Nearly everywhere I may go, I will meet people who know how to read.

The world is a wonder. Let’s not doubt it. The creative power of humankind has yielded a modern world that is safer, richer, more connected, more mobile and full of opportunity for more people than our ancestors could have imagined.”

Where did all this progress come from? In addition to the inherent creative power of humankind, progress is nurtured by education, wherein creativity and curiosity turn knowledge into progressive action: Machines. Ideas. Institutions. Literature and art.

Maybe even better government. Countries, for example, where everyone has health care, and citizens embrace collective efforts to address global issues like climate change. Progress—if you define progress as moving forward to solve problems, bring good things to life.

Possibly you’re raising your hand right now, itching to tell me that there are multiple definitions of progress and progressivism, or that the opposite of conservative is not liberal, but progressive. I would suggest that what we’re seeing now—the movement to damage public education—is not conservative. It’s authoritarian vandalism. But let’s try to agree on a definition of what it means to be progressive.

Miriam-Webster: A left-leaning political philosophy and reform movement that seeks to advance the human condition through social reform. Adherents hold that progressivism has universal application and endeavor to spread this idea to human societies everywhere.

It was not surprising to read this, in a must-read piece by Megan O’Matz and Jennifer Smith Richards at ProPublica: “In a 2024 podcast, Noah Pollak, now a senior adviser in the Education Department, bemoaned what he sees as progressive control of schools, which he said has led to lessons he finds unacceptable, such as teaching fourth graders about systemic racism.”

Progressive control of schools? Seriously?

Speaking as a person who has spent decades working in public schools and with public school teachers across the country, schools are generally among the most conventional and cautious institutions on the planet, subject to pressures and opinions from a wide range of (often clueless) critics. And likely headed by someone who adamantly does not want to get phone calls from honked-off parents.

I also say this as a person who taught fourth graders about systemic racism, in a general music unit from our REQUIRED music textbook, a collection of songs (Follow the Drinking Gourd; Swing Low, Sweet Chariot; Bring Me Little Water, Silvie and others) plus some pretty neutral fourth grade-appropriate text about the African formal and rhythmic roots of American popular music.

We were sitting on the big, round rug and one of the fourth graders asked why so many African-American songs (again, songs in our traditional music series) were about God. If their lives were so bad, he asked, why did they believe in heaven? It was a good question and led to an equally good discussion about what happens when people are oppressed—how they maintain cultural traditions, and hope.

If progressivism is about advancing the human condition, who’s against it? Besides the handful of people running the fatally compromised US Department of Education? The very people to whom diversity, inclusion and equity—progressive values– are anathema.

Convincing people that public school educators are a) raging leftists and b) persuading their students to defy their parents and adopt outrageous worldviews, then calling that progressivism is a fool’s errand. And 70 percent of the people who have first-hand experience with that—parents—generally believe that their public schools are doing the job they want them to do.

But societal shifts happen when false and unsubstantiated statements are repeated so often they become common knowledge. So be prepared to hear a lot of blah-blah about “progressive” public schools in the near future.