…that isn’t in the regular, designated curriculum.

So many things, right?

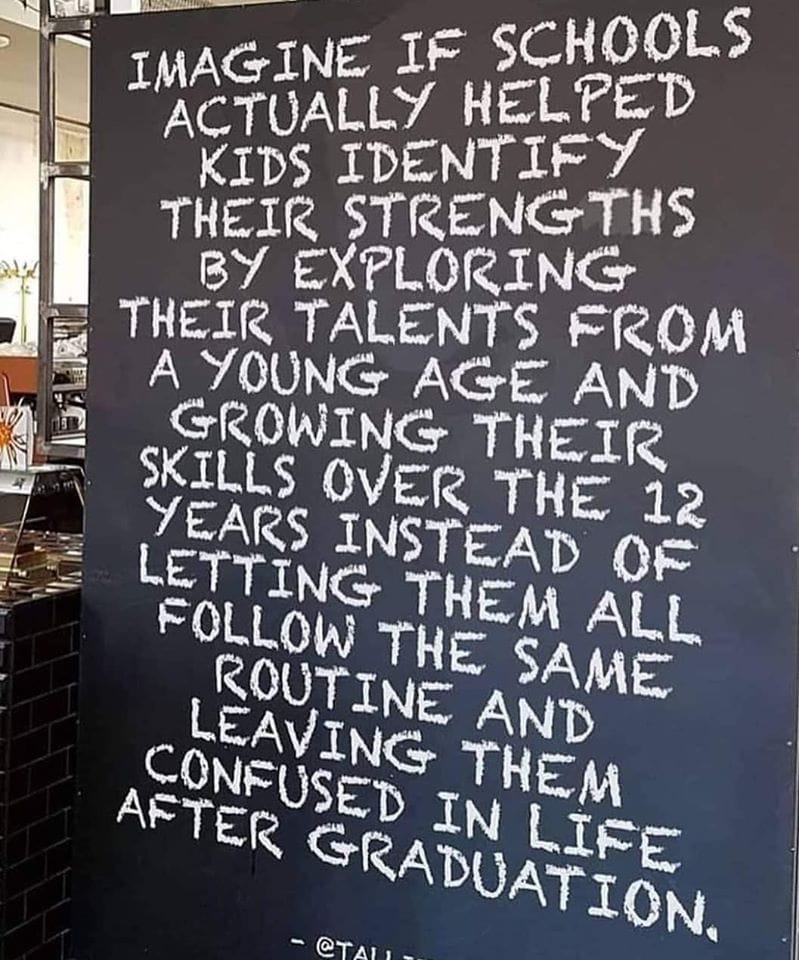

You’ve undoubtedly seen the memes: Why aren’t schools teaching personal finance, including credit cards and taxes? What about home and car repairs? Insurance? First aid? Time management? Study skills? Stress relief? How to find a job, feed yourself and do your laundry?

Frequently, the post will draw supportive comments, ranging from unwarranted criticisms of what schools actually DO attempt to teach, to nostalgic memories of the days when all the boys had to take woodshop in 9th grade. There was never a shortage of handcrafted birdhouses in those days, by golly.

And—dipping into fantasy here—wouldn’t it be great if schools picked up responsibility for teaching all the life skills one needs to be a fully functioning adult? In addition to math, languages, history, sciences and literature, of course.

The ones that really get to me are the folks begging schools to teach good interpersonal communication and conflict resolution, with maybe a dash of leadership thrown in, but then picket the school board because Mrs. Jones has launched a social-emotional learning through mindfulness (SEL) program for 4th graders, and you know what that means.

A friend just posted a meme reminding us that 100 years ago, students were learning Latin and Greek in high school, and now, high school graduates are taking remedial English in college.

There are multiple responses to that one, beginning with an accurate explanation of just who went to high school in the 1920s—and what percentage of students go to college today.

The utility of studying Latin and Greek (or Logic and Rhetoric) in 2024—as opposed to, say, Spanish or robotics—is debatable, as well, but everyone understands the underlying purpose of such a meme: Schools today are failing. Tsk, tsk. Discuss.

If you’re a long-time educator, you learn to take these comments in stride. Just more evidence that everyone’s been to school, and thus believes they understand what schools and teachers should be doing. It’s an evergreen cliché that happens to be largely true.

But there are a couple of points worth making:

- The required curriculum is overstuffed already. Way overstuffed, in fact. Michigan—which has a tightly prescribed “merit curriculum” for HS students– just added a requirement that all students take a semester-long course in personal finance. This can take the place of a math course—or a fine arts course, or a world languages course. Every time a requirement is added via legislation, students who want to take four years of a foreign language, or play in the orchestra for four years, have to juggle their schedules and make unpleasant choices.

There simply isn’t enough time in the day to cover everything—and it’s maddening to have someone at the state Capitol directing your path by limiting your choices.There are lots of important things to know about adulting, and you only get so much time to go to school for free, in the U.S. Expecting schools to teach things that used to fall squarely into the purview of parent responsibilities, without providing additional time and resources, is unfair.

- This is educators’ professional work. Let’s take Mrs. Jones, the 4th grade teacher who decided to incorporate an SEL program into the daily life of her class. She’s doing that for a reason, I can assure you. Either these techniques have worked in the past to create a happier classroom atmosphere, or this class is particularly conflict-prone. She’s trying to make it possible for students to learn the other (required) things, by focusing first on communication and techniques that calm students, helping them focus.

Do educators sometimes get students’ curricular and personal needs wrong? Sure. But they are the first line of defense, and best positioned to incorporate non-disciplinary work (like time management, stress relief and how to properly thank someone) into the classroom. And all of them appreciate these things being reinforced at home.

- You can’t get away from teaching things that fall into the wider scope of how to be a successful adult and citizen, as a schoolteacher. You’re always, always modeling, correcting, observing and suggesting behaviors, whether your students need help getting into their snowsuits or help in getting over a failed romance. Even if you’re teaching AP Calc, there will be inadvertent lessons in addressing challenges, persistence and the value of studying something so abstract and elegant.

There is a prevailing belief, especially in the past couple of decades, that the only way Americans can compete in the global economy, maintaining our preeminent position, is to “raise the bar.” This usually translates to harder coursework, required earlier in a student’s academic career, monitored by increased testing. More top-down control. More competition.

When you drill down far enough, what’s missing is a clear objective for public education. Are we, indeed, trying to help every child reach their full potential (in which case, bring on the handcrafted birdhouses and mindfulness)—or are we trying to strengthen the economy by creating skilled and compliant workers?