I’m old enough to remember…

When we were all sharing data in the 1990s about how boys got called on more often, and their comments got more affirmative responses from their female teachers. We actually had a professional development session at my school on the topic, urging us to self-monitor our teaching practice, to encourage girls to speak up in class and to acknowledge their skills. There was, of course, pushback, mainly from veteran (male) teachers. But we were dedicated to the idea of building confidence in girls.

I’m also old enough to remember an honors assembly where a (female) math teacher in my middle school, when presenting a top award from a statewide math contest to a young lady, remarked to everyone in the assembly that “the girls don’t usually try very hard on these competitive tests.” Parents and teachers seemed to take her comment in stride—and when I asked her about it later, she defended the remark and expanded on her belief that boys were just naturally better at math.

It must be scary for folks whose ingrained beliefs about male vs. female proclivities are now riding up against data on the next generation of our most powerful professions, while local community colleges are trying to attract male students by offering courses in bass fishing?

In ABA-accredited law schools, women now constitute 56.2% of all students, outnumbering men for the eighth consecutive year. Historically, law schools were dominated by men. In the 1970s, only 9% of law students were women.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), in the 2023-2024 academic year, women accounted for 54.6% of medical school students in the United States. This marks the sixth consecutive year that women have made up the majority of medical school enrollees.

So–I was eager to read a recent article in Edweek: Middle School Is Tough for Boys. One School Found the ‘Secret Sauce’ for Success.

Who doesn’t want to know the secret sauce for boys, since their dominance seems to be fading and their profile as reluctant learners rising?

Let’s cut to the chase. That sauce, those school leaders say, consists of reducing rules, trusting the boys, giving them more hands-on responsibilities and real-world applications for the things they learn (like DJ-ing a dance, designing a vehicle in teams—or not requiring hall passes).

Now, all those ideas sound fine to me. They worked when I used them, for 30 years or so. Treat your students (male, female, anywhere on the gender spectrum) with trust and give them real tasks to do. Challenge them, but build personal autonomy. Easy peasy.

However– why would we save that good stuff just for boys?

How much influence do schools have on boys’ ambition, effort and moral formation? And what’s happened to American boys in the past decade or so?

Lately, there’s been a lot of chatter about Adolescence, a four-episode drama about an angelic-looking 13-year old boy who kills a female classmate. I can’t watch stuff like that, but I am horrified by comments from teachers who say that “incel culture” depicted in the show is growing, in middle and high schools: Teachers described boys uttering sexual slurs about them in the classroom, talking about their bodies or just generally expressing a loathing of women. One boy, who had been harassing [teacher] all year, ended up spitting in her water bottle. Witnessing the harassment of their female students was also painful for these teachers.

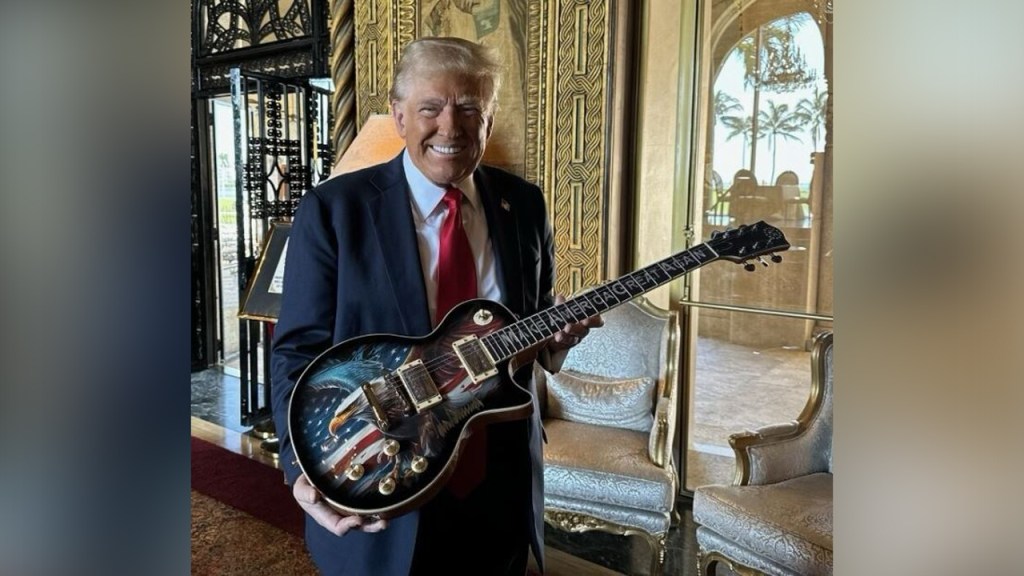

And here’s a fact that scares the daylights out of me. In the 2024 election, in the group of voters aged 18-25, the gender gap was 20 points. Way more young white men–63%, first and second-time voters–cast their ballots for Trump, a man convicted of sexual harassment, a man who ordered 26,000 images removed from the Pentagon’s database and website, because they featured people of color and women.

As author and educator John Warner writes: All progress has been met with backlash and Trump II could really be seen as a backlash presidency, a man who proudly preys on women as President, surrounded by others who seem similarly oriented. What is the positive message about gender equality for young men when joining the broligarchy seems to have real-world benefits?

While it’s important for boys to have personal agency in their learning, and be trusted by their teachers, boys need to have role models, as well. Who are we offering up as heroes, men whose lives and actions are worthy and admirable? Men worth emulating, who care for their spouses and children, men whose values serve as guardrails, men who are civically engaged?

Boys are growing up in schools where their neighbors on the school board worry about “weaponizing empathy.” Where men at the highest levels of government power are uninformed bullies, careless in their actions but never held accountable.

I attended graduation ceremonies annually in the mid-sized district where I taught. Usually, I was directing the band, but sometimes, I sat on the stage with any of my faculty colleagues who felt like giving up a Sunday afternoon and putting on a gown and academic hood.

The students sat in the center section of the auditorium, and I was always bemused by the front row of boys—how many of them were wearing shorts under their gowns, and rubber shower slides, with or without white socks. They were manspreading and snickering with each other, and I thought about how many of them were already 19, having been held back in preschool or kindergarten so they’d be bigger, and more likely to make first string, come middle school.

In another age, those young men would be on their own, perhaps married, perhaps working toward a house or business, perhaps serving in the military. But we gave them an extra year in school.

When perhaps what they really needed was real responsibilities, and someone to model how to live a life of integrity.