I’ve read a lot of books this year—114, according to my Goodreads account (more on that in a minute). Interestingly, not many of them were five-star reads. Kind of like the discourse around 2025 in general: a whole lot going on, little of it particularly enlightening or inspiring.

I tried to focus on fictional books, because the large bulk of what I read, day to day, is newsletters and newspapers, op-eds and social media posts, as we collectively watch the Great American Dismantling. Fiction serves as escape, and even medicine for the disheartened soul. Quality fiction, that is—books that have something to say while entertaining the reader.

I’m sharing eleven good books I read in 2025—two non-fiction, nine fiction, plus two series that I’ve come to love.

But first, a question: Is anyone using Storygraph to record your reading? I’d like to disengage from Goodreads—it’s a Jeff Bezos thing, plus there are now some irritations around their features. I got a Storygraph account but found it confusing and cluttered.

One of my dearest friends, with whom I exchange book titles regularly, finds all on-line book-reading apps confusing and unnecessary, and still records her reads and to-reads in a spiral notebook. At the end of the year, she counts. Or doesn’t. Because how many books doesn’t matter—it’s about how much you enjoyed the books, where they lead you.

I wish I could go full-blown purist, too. But I like tracking not only how many, but whether I’ve already read something (series titles will fool you, when they all sound the same). Any advice on book apps?

So here are my best 2025 reads—some new books, some merely recent. If you want to read my reviews (they’re short), click on the bolded title.

Non-fiction

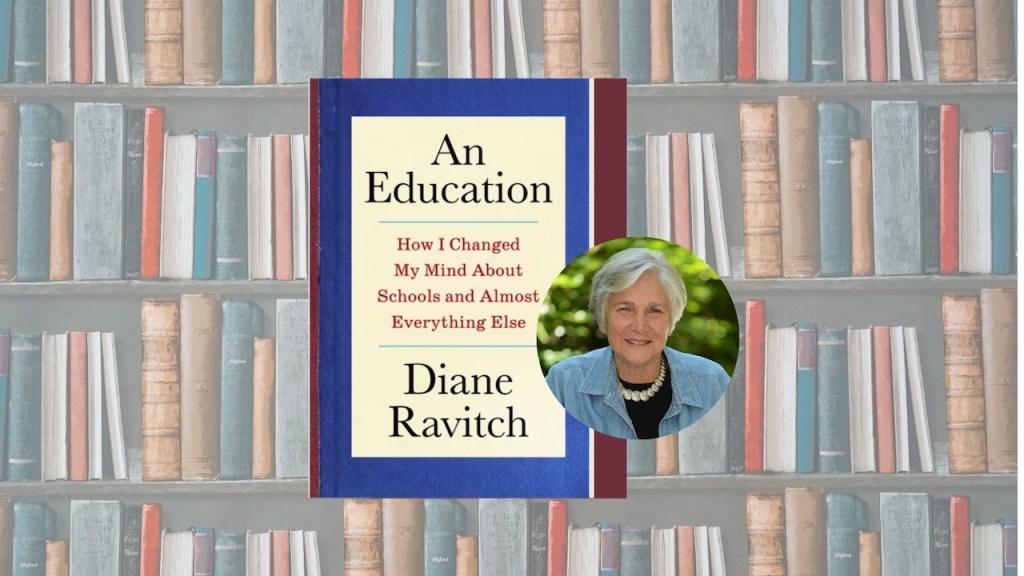

I only read two memorably great non-fiction books this year, and both were memoirs written by women I deeply admire. I’d put Atwood on my list of ten favorite authors, and while her memoir is endlessly detailed, it’s also full of snark and deliciously tart observations. I wrote a whole blog (linked below) on Ravitch’s book, a behind-the-scenes look at the life of a personal education hero.

Book of Lives (Margaret Atwood)

An Education: How I Changed My Mind about Schools and Almost Everything Else (Diane Ravitch)

Fiction

It wasn’t a great year for fiction reading. Maybe it was the heavy lifting fiction had to do to drop me into another world without being lightweight or predictable. I have collected a couple dozen promising books on my e-reader to take on a winter vacation, because it’s clear we’re in for another year where reality is intolerable. In the meantime, here are nine—very different–books I could recommend.

The Heart of Winter (Jonathan Evison)

The Frozen River (Ariel Lawhon)

The Wilderness (Angela Flournoy)

Heartwood (Amity Gaige)

So Far Gone (Jess Walter)

The Jackal’s Mistress (Chris Bohjalian)

James (Everett Percival)

The Ministry of Time (Kaliane Bradley)

The Safekeep (Yael van der Wouden)

I’d also like to mention two book series that have reached must-read levels for me, like the books of Louise Penney, Donna Leon, John Sandford or others whose latest installments are anticipated returns to familiar worlds and characters.

Thursday Murder Club (Richard Osman)

I found the first book in the 5-book series cute and cozy, but unremarkable. But with each outing, I added stars, and the fourth book was outstanding. The most recent—The Impossible Fortune—was just as good.

At Midnight Comes the Cry (Julia Spencer-Fleming)

I was pleased to see that Spencer-Fleming’s 10th outing in her small-town cop-meets-Episcopal priest series made the NYT list of best mysteries of 2025. It may be Spencer-Fleming’s last book, so if you want to set off on a series, give it a try.

And now—talk among yourselves. What did you read and love? Disagree with my list?