Earlier this year, I wrote a piece about people whose core political beliefs represented the sincere hope that the country would radically improve under the second Trump term. It was titled Who ARE These People?

It represented a sentiment I hear all the time: I can’t believe there are people who think Trump is the second coming. Who in their right mind could see him as a transformative leader? Who does not perceive the grifting, the rank incompetence, the prejudice, the lies—and the danger to a functioning democracy?

Companion questions: What percentage of the population understands and genuinely embraces Trump and the cadre of people surrounding him, currently disassembling our government? Who ARE the people who think it is Trump’s right to tear down the East Wing of the White House? Who ARE the people who believe that dangerous crime is surging, that food prices are dropping, that cutting SNAP benefits and Medicaid will teach those lazy slackers a lesson? Oh—and don’t use Tylenol!

And—key point—where are those folks getting their information? How do we counter obvious lies? Including lies published on official government websites and broadcast in airports?

Yeah—I know. You read this stuff, too—eye-popping, outrageous stories—and ask the same questions.

Maybe you’re wondering if teachers—underpaid and overworked—could have done more to establish the habit of questioning authority, discerning which evidence and rhetoric are reliable. Examining biases, looking at turning points in history, and so on.

Where were the people that Lucian Truscott calls yabbos educated? Who suggested to them that racism, sexism, and deceit were OK, if they were means to an end?

It’s exhausting.

This week Jonathon Last wrote this on The Bulwark:

‘Some large portion of voters do not appear to understand elementary, objective aspects of reality. We have jobs and lives, too. If we can understand reality, then they should be able to as well.

It does seem as though the last Democratic administration focused like a laser on economic issues. It managed the economy well, avoiding a recession and achieving a soft landing. It passed major, bipartisan legislation around Kitchen Table Issues like infrastructure spending. It kept the economy strong, with historically low unemployment and real-wage growth. It did not try to ban assault weapons but instead passed a gun-reform bill so sensible that it received bipartisan support. It successfully negotiated the most hawkish immigration reform bill in American history, only to have it sabotaged at the last minute by Donald Trump. These are actual things that happened in the real world over the course of 48 months.

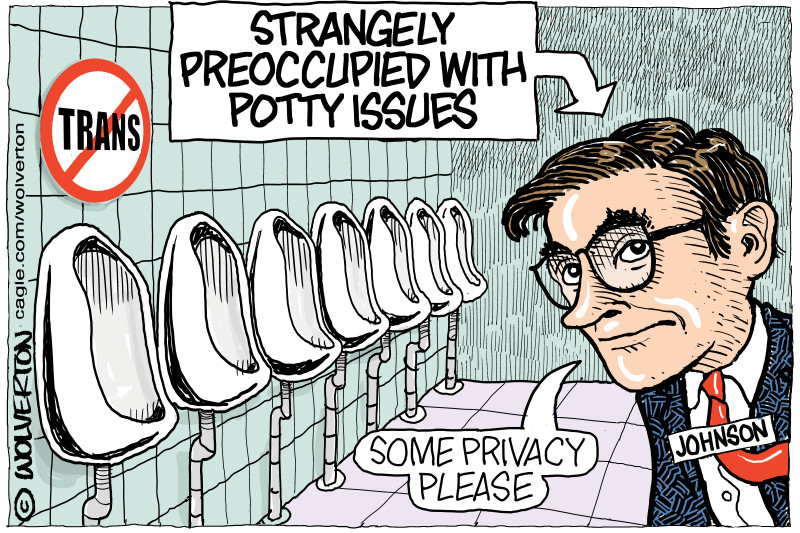

Yet somehow all of this activity was invisible to voters? While these same people were highly attuned to the number of times LGBTQ appeared in the Democratic platform?

Which is it? Are the voters oblivious? Or are they discerning? Or does it depend on the situation: Willfully blind to some facts, but hyper-attuned to others?

Another theory is that voters are largely incapable of discerning reality, so expressed policy preferences matter much less than atmospherics and vibes. This theory holds that voters will respond more to entertainment or projections of strength than to a policy-based focus on the Real Issues.’

Whew. But probably—yes. Incapable of distinguishing reality from wish fulfillment. Rumor from news. Fool me once, twice, keep on fooling me, but it’s easy to vote (if you vote at all) by habit, not by analysis:

‘In fact, research into voting patterns in America suggests that it honestly doesn’t matter that much who or what a candidate looks like. When people go into the voting booth, they vote Republican or Democrat. When push comes to the ballot box, that little R and D matter more than all the Bud Light in the world.’

So. Here’s the real nub. If a third of American voters can’t tell fact from ugly fiction, or actually prefer to be governed by racists, quacks and the mentally diminished, if they are Republicans, what are we to do? Is this a permanent shift in American politics? Or are there ways to rebuild trust in our neighbors, our institutions, our national pride?

We can’t turn away if we want a just society. We can’t rely on the hope that seven million citizens singin’ songs and carryin’ signs will be enough. Because the destruction is too speeded up and too dangerous. Rachel Bitecofer reminds us of a single line from a Warsaw Ghetto diary:

‘The writer had already lost his home, his livelihood, and most of his family. Rumors were spreading that deportations east meant death, and he wrote “We hear that being deported East means they are going to kill us, but there’s just no way the Germans would do that.”’

Lately, I have tried to focus on ways to reconnect with those who might regret their vote, or whose habitual partisan roots might finally seem like a bad habit. People who are becoming increasingly alarmed at seeing Bad Things happen, even though they remain safe and unharmed. Two thoughts:

(from Colorado organizer Pete Kolbenschlag):

‘This is the Ditch Principle: Your ditch neighbor may disagree with you about everything except keeping the water running — so you start there. The neighbor who might pull you out of a snowbank doesn’t stop being your neighbor when you disagree about politics. Rural communities practice interdependence because isolation kills.’

(from Philosophy Professor Kate Manne):

‘How has Mamdani, an unapologetic socialist—and progressive Muslim and advocate for Palestinian rights—pulled off the feat of likely winning against the odds, against the tide, and against all early predictions? In part, I think, by calling forth the best from voters, rather than kowtowing to existing polling data.’

As a veteran educator, I hate saying this—but I don’t think this is something learned in required coursework, no matter how great your Civics curriculum is. Schools are a kind of stage, where society plays out its biases and beliefs, bad and good. Incorporating content standards into becoming a more responsible and caring human is something that can be modeled—but not tested and ranked.

There is no class syllabus that prescribes pulling your neighbor out of a snowbank—but if your dad pulls over on a snowy day to get a speeding classmate out of the ditch, you’ve learned an important lesson in interdependence. Likewise, there are teachers who call forth the best from students, by integrating facts and skills with compassion and curiosity.

I wish I had answers for these questions. What do YOU think?