There are so many things to be said about the ongoing demolition of the American government that your average reader—even someone who follows politics closely–can’t keep up. Everything from the Massive Erroneous Deportation to the Declaration of Independence in the Oval Office to the biggest upward transfer of wealth in history. Not to mention Goodbye to the Department of Education.

Lots of great writing about where we find ourselves as a nation, as well—I am learning to get along without the Washington Post, with the great political commentary coming from independent newsletters like The Contrarian, Meidas, Robert Reich, Heather Cox Richardson, Lucian Truscott, The Education Wars and the Bulwark, which are only the ones I’m currently paying for. Can’t add much, beyond my personal open-mouthed horror, to the wall-to-wall political coverage available.

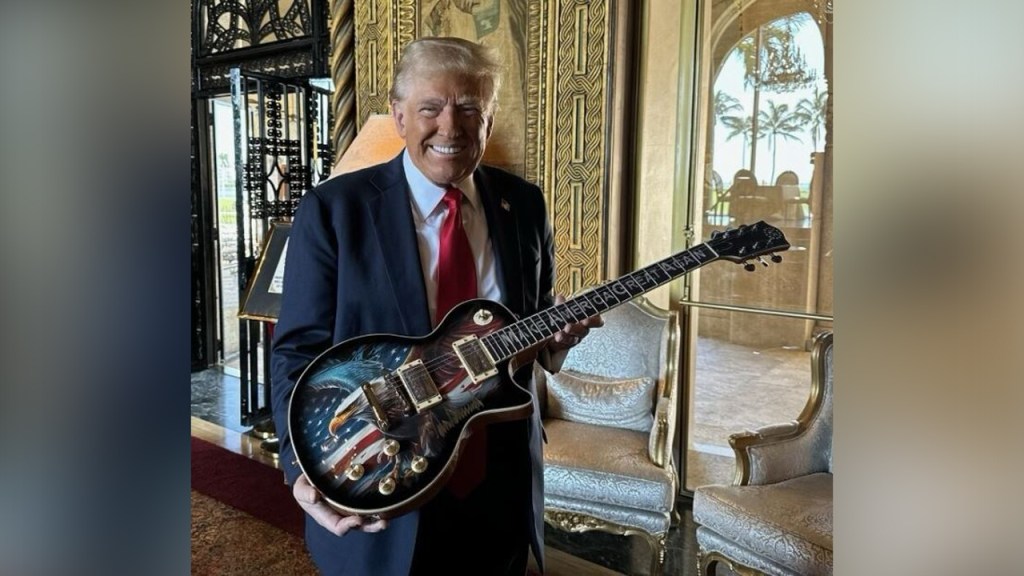

However. Here’s one inane Trump declaration where I have considerable expertise: Touring Kennedy Center, Trump Mused on His Childhood ‘Aptitude for Music.’

In case you’ve missed it (and you’re forgiven if you have): President Donald J. Trump — who recently overhauled the once-bipartisan board of directors at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and installed it with loyalists who elected him to serve as its chairman — held court Monday in a place that he had not publicly visited during either of his terms in office: the Kennedy Center.

Remarks were made to the Washington Post by Trump officials who recently toured the arts venue and described it as “filthy,” noted that it “smelled of vomit,” and added that they “saw rats.”

But not to worry! Trump alone can fix the Kennedy Center. In fact, Trump—who could have been a superb musician, if his parents hadn’t pushed him into becoming an outstanding athlete and phenomenally successful businessman instead— can add “born arts connoisseur” to his already-substantial resume’. Because ‘the test’ showed what we’ve all missed: the guy who bragged about punching out his music teacher in second grade was really an untapped musical genius.

First of all: Hahhahahhahaha.

Like all Trump anecdotes—Sir! Sir!– this one is mainly bullshit: He told the assembled board members that in his youth he had shown special abilities in music after taking aptitude tests ordered by his parents, according to three participants in the meeting. He could pick out notes on the piano, he told the board members.

If you polled actual music teachers, all of them could tell you stories about small children whose parents considered them exceptional, because they could dance to a beat , clap a rhythm or pick out a tune on the keyboard. Many of them had a great-grandmother who taught piano or uncle who was a whiz on the saxophone—thereby confirming that their talent was inherent, according to mom.

Some of those kids (especially the ones whose parents encouraged practice and persistence, attending every concert) turned out to be good musicians, after some basic musical instruction. Others, not so much.

Second: Testing children’s innate musical ability has fallen out of favor, for the same reasons that other standardized testing has been rightfully criticized. In the post-war years, a ‘musical abilities test’—the Seashore Test—was popular, often used to determine who should get to use expensive school-owned instruments. I took it myself, in the 4th grade.

What the Seashore Test did, mostly, was identify kids who had some musical experience—piano lessons, singing in the church choir, music-making in their families. Because the more you do music, the better your ‘ear’ and sense of rhythm. Kind of like the way kids who go on family trips to the library or museum get a leg up on other kids, when tested on their reading abilities or content knowledge.

Is there such a thing as talent? Sure. But testing as a means of determining talent—or taste, or creativity—when the testee is a child is pointless. Genuine, exceptional talent emerges as a result of passion and tenacity and, sometimes, good luck.

Here’s a story about my own failing in assessing talent, as a music teacher.

Why did such testing fade away? Because it missed a lot of students who became strong musicians—singers and trombonists, the lead in the school musical—down the road.

Lesson learned: ALL children should all enjoy making music in our schools. Because you never know if someday your child might be Chair of the Kennedy Center Board.