My introduction to Diane Ravitch: I can’t remember precisely which education conference it was, but I was in graduate school, so it was between 2005 and 2010. Ravitch had just begun writing her Bridging Differences blog with Deborah Meier at Education Week, a sort of point-counterpoint exercise. I had also just read her book The Language Police for a grad class, and—although she’d always been perceived as a right-wing critic of public education—found myself agreeing with some of her arguments.

She was on a panel at a conference session. I can’t remember the assigned topic, but after the presentation was opened up to questions, they were all directed to her. And she kept saying smart things about NCLB and testing and even unions. Finally, a gentleman got up to the microphone and said:

Who ARE you—and what have you done with Diane Ravitch? The room exploded in laughter. Ravitch included.

Ravitch has published two dozen books and countless articles. She is a historian—making her the Heather Cox Richardson of education history, someone who can remind you that when it comes to education policy, what goes around comes around. Her previous three books were, IMHO, masterpieces of analysis and logic, describing the well-funded and relentless campaign to destroy public education here in the U.S.

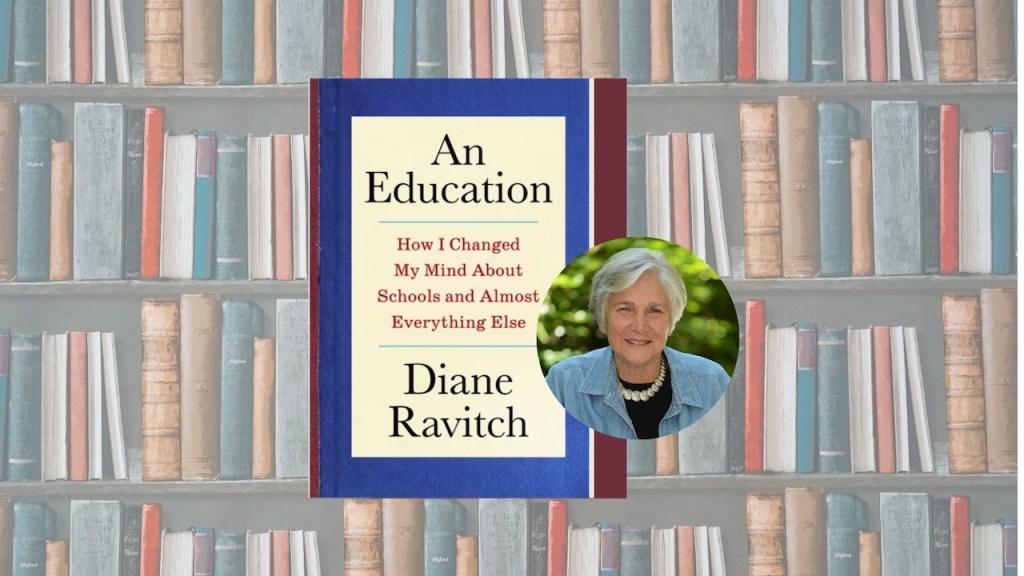

And now, at age 87, she’s written a kind of expanded autobiography, An Education: How I Changed my Mind about Schools and Almost Everything Else. She tells us how her vast experience with education policy, across partisan and ideological lines, has left her with a well-honed set of ideas about how to build good schools and serve students well. How, in fact, to save public education, if we have the will to do so.

You get the sense, as Diane Ravitch wraps up “An Education,” that she is indeed wrapping up– she sees this as her last opportunity to get it all out there: Her early life. How she found happiness. Mistakes and regrets, and triumphs. It’s a very satisfying read, putting her life’s work in context.

For her followers and admirers (count me in), the book explains everything about her beliefs. Her working-to-middle-class roots and her family’s loyalty to FDR and what the Democrats stood for, during post-World War II America, go a long way to explaining how she eventually (with some major diversions) became an articulate proponent of public education.

I’m glad she included a nostalgic portrait of growing up in TX with a hard-working mother and feckless (and worse) father. The glimpses we get into public education in TX in the post-war years resonated with me–and it’s easy to see how going far away to an Ivy League college shaped her entire adulthood. Her classmates at Wellesley, like Ravitch, were ambitious and curious; I’m old enough to remember a time when female ambition was suspect.

The most fascinating part of the book, for me, was the middle third, where she wrote about researching the history of public education and being asked to sit on prestigious boards and serve as Assistant Secretary in the George H. W. Bush Department of Education. There’s a whole chapter on Famous Education Opinion Leaders (many of whom are still working to suppress full public education) taking Diane to lunch, tapping into her work ethic and offering her opportunities to be part of the power structure, to write and speak (and—big point—learn what they’re really up to).

N.B.: Award-winning teachers are also often asked to become part of the education establishment by sitting on boards, writing op-eds, and serving on task forces– and it can be easy to feel as if you’re contributing, at a higher level, when what you are actually doing is giving credence to people who have a very different, but hidden, agenda.

The final third of the book is the Diane Ravitch most educators know and respect. Her observations come from swimming in the ocean of education policy for decades– and they’re accurate. I expect Ravitch to continue to blog and write and speak, as long as she is able. She is the rare voice in education that has examined education ideas across the spectrum and found many popular notions weak or dangerous.

The book is a fine testament to a life spent searching for the truth about public education.

Five stars.