Some years ago, when talk radio ruled the discourse, I was listening to a national teacher union leader talk with a right-leaning—and nationally recognized—radio host. The topic was teachers as catalysts for improving public education.

The union leader mentioned National Board Certification as a model for identifying teacher leaders, the kinds of folks whose classroom expertise was validated, whose ideas about advancing public school achievement could be valuable.

Radio host: So what do these so-called nationally certified teachers have to do to prove they’re good?

Union leader: Well, they are assessed on five core principles of pedagogical excellence. The first one is knowledge of their students, and what they need to succeed. Teachers need to be committed to their students and their learning.

Radio host (full of snark): So good teachers just have to love the kids? Hug ‘em until they drop out?

That conversation—which could have featured any of the podcasters grabbing the public ear in 2026—is familiar. Lots of media figures seem to feel that the cure for “fixing” public schools is coming down hard on kids, raising the bar, forcing them to pull up their (nonexistent) bootstraps and get to work, damn it.

I thought about that conversation when I read this headline:

‘Valentine’s Day events around Minneapolis take on the ‘horrors of the world’in the Minneapolis Star.

Tag line: After a heavy start to the year, some Minneapolis residents are using Valentine’s Day to love thy neighbor.

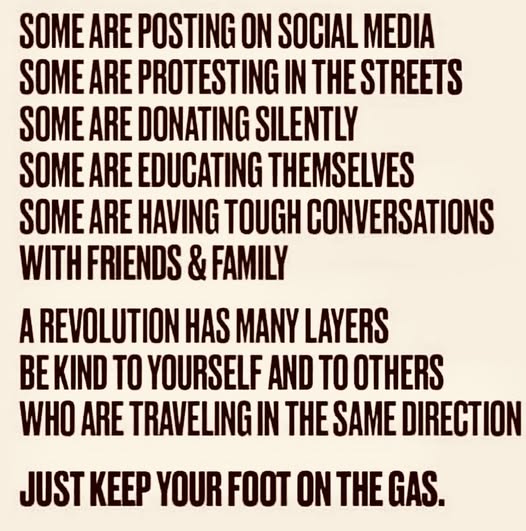

Bingo. ‘Love thy neighbor’ is currently working in besieged communities like the Twin Cities. It works in the classroom. In fact, getting along is Job #1 in classrooms.

Kindness. Patience. Respect, a two-way street.

And then—and only then—engagement. Communication and collaboration. Joy, even. Deep learning.

Why is that so hard to believe—or understand? Human beings seldom respond to fear, threats, isolation or humiliation. They shut down—or fight back. People who relish the idea that the modern-day equivalent of smacking kids’ hands with a ruler is a productive idea are wrong.

From the National Education Policy Center newsletter:

…70% [of surveyed U.S. principals] said that “[s]tudents from immigrant families have expressed concerns about their well-being or the well-being of their families due to policies

or political rhetoric related to immigrants.” These impacts on schools across the nation are shockingly pervasive, and those impacts can be devastating, even for those students not directly targeted. “Fear undermines the ability of public schools to foster a civic community,” [survey author John] Rogers told Education Week last month.

This is unsurprising—and none of this is new. The ecology of school success has always centered on relationships. When everyone—and this includes teachers—feels comfortable and part of the community, stuff gets done.

In fact, Herbert J. Taylor created a set of ethical guidelines for the Rotary Club in 1932 that might be useful for anyone concerned with kids’ well-being in 2026. It consists of four questions to guide all our decisions:

- Is it the TRUTH? 2. Is it FAIR to all concerned? 3. Will it build GOODWILL and BETTER FRIENDSHIPS? 4. Will it be BENEFICIAL to all concerned?

Is our government using any of these old-fashioned, even corny, principles to guide their actions around immigration? Or election security? Or ethical business practice?

Do we have to love our students? No. That’s not reality—or practical.

But caring for each other may be the only thing that will save us, in these dark times.

Happy Valentine’s Day.